The plantations sector of Sri Lanka has had the rare distinction of providing the testing ground for finding out to what extent state control can be successful in managing large tracks of agricultural land.

Having experienced the dis- mal side of a once popular process of nationalization, the sector is presently turned around by the private sector management. Six of the large plantations have already been fully privatized while the process is expected to be completed perhaps by the end of the year.

This sector which was efficiently manufactured by the British under the Agency House System, not only formed the backbone of the country’s post-independence economy but was often cited as the reason for Sri Lanka’s prosperity in the 1950’s, compared with some of her neighbors in the region.

With the decision of the then government to introduce land reforms and to nationalize all local and foreign-owned plantations and to fix the land ownership ceiling to a maximum of 50 acres per person British interests shifted to countries like Kenya, Tanzania and Malawi.

With the state takeover of the estates, 496 tea, rubber and coconut estates were placed under the management of two agencies created for the purpose, namely Janatha Estate Development Board JEDB) and State Plantations Corporation (SPC). Thus they became two of the largest agricultural corporations in the world.

Like many other state institutions these corporations became plagued with problems such as waste, corruption and inefficiency resulting in huge losses during most years except for a few profitable years which were mainly due to market factors. Political interference, lack of accountability and wage setting were some of the other factors which contributed to this situation.

The size and the bureaucratic nature of these organizations as well as a heavy tax burden placed on the sector led to an average monthly loss of Rs 400 million. This situation resulted in the gradual decline of the plantation sector which was the highest foreign exchange earner in the pre- 1970 period, with other industries such as garment and tourism taking its place.

The two management agencies were expected to deal with issues such as productivity, increasing productive employment and quality standards, cost of production, village integration etc.

However these agencies lacked the vision and leadership that could effectively handle these issues.

Capital was infused to these plantations under various foreign funded rehabilitation programs to help overcome problems such as GERAGAMA ESTATE …if the full impact of private management is to be realized it is essential to have a long term sustainable arrangement. low productivity, high cost of production etc. However all these measures failed to bring about any significant change in the overall situation, thus raising fundamental issues on the commercial viability of the whole sector.

A Plantation Management Restructuring Unit set up under the aegis of the World Bank studied alternative approaches to man- age state-owned plantations and recommended the introduction of private sector participation in the management of these estates.

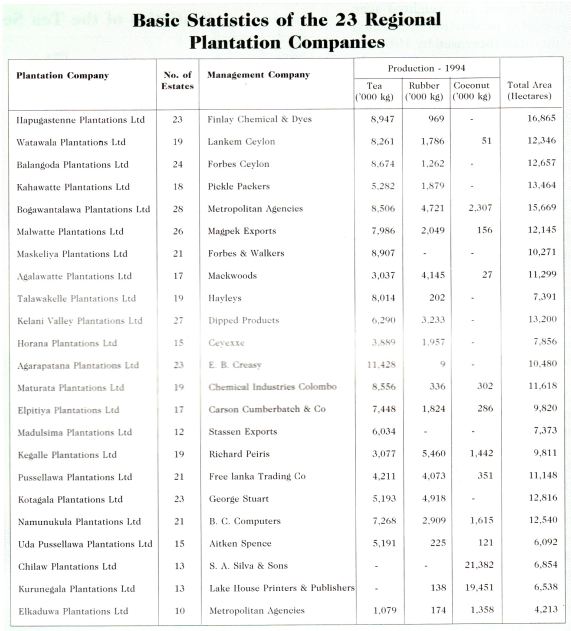

Accordingly, in 1992, 450 estates belonging to the SPC and JEDB were distributed among 23 Regional Plantation Companies (RPC) and given over to the private sector under 5-year management contracts. The objective was to introduce the private sector norms of management with greater responsibility and accountability.

Though the system produced some good results like increased efficiency and higher productivity. The RPC’s had to face major problems such as their inability to obtain long term debt as a result of the short term management agreements. This gave rise to the idea that if the full impact of private management is to be realized it is essential to have a long term sustainable arrangement. Thus the government decided to sell an equity stake to the private sector.

Arrangements were made to divest controlling interests of 51% Out of the balance equity, 19% was to be retained with the government to be divested at a latter

stage, while 20% was to be offered to the public. Like in all other privatizations, 10% of the shares were to be given to the employees. Arrangements were also made for the government to keep a golden share which gave several special rights.

Under this arrangement six of the 23 plantations Agalawatte, Kegalle, Kelani Valley, Bogawanthalawa, Horana and Kotagala have now been fully privatized. All these companies are now quoted at the Colombo Stock Exchange while their shares are being transacted at prices ranging from Rs 34 to Rs 41.50.

Out of the remaining companies the government has divested controlling interests of 51% in 7 36 BUSINESS TODAY June 1997 Sri Lanka’s yield and rates of productivity are the lowest while the cost of production is the highest RPCS namely Hapugastenne, Watawala, Balangoda, Maskeliya, Agarapatana, Madulsima and Udapussellawa plantations. Maturata,

Out of the remaining RPC’s, Malwatte and Namunukula plantations are to be divested before the first week of June while Eladuwa, Elpitiya and Kahawatte are also to be privatized soon after. The government has still not taken a decision as to when the balance four plantations would be privatized.

However, according to the sources, the privatization of the entire sector is expected to bet completed within this year, as the private sector has already demonstrated that with good management the sector could be turned around and made profitable.

Sri Lanka is presently the largest exporter of bulk tea, while among the country’s agricultural exports tea continues to be the major export crop accounting for around 60% of the total agricultural exports.

However, the tea industry’s performance here compared to that of her competitors has been poor. Sri Lanka’s yield and rates of productivity are the lowest while the cost of production is the highest compared with the major producers such as India, Kenya, Indonesia and Malawi.

Sri Lanka’s major buyers of tea in recent times have been the CIS, Turkey, Syria, Saudi Arabia, EU, Egypt, Jordan, Japan, UK, Germany, Iran and Chile.

At Colombo tea auctions the gross sales average has been Rs 99.76 per kg for high grown teas, while for medium and low growns the prices were Rs 92.27 and Rs 110.63, respectively.

Major tea brokers in Colombo said that this year the market has been performing well and expected that the same price levels would be maintained throughout the year.

‘Due to favorable weather a massive crop is expected in May resulting in a large sale in June

and if the market can take it with the same price trends I am sure that the prices will stabilize thereafter’, a director of a major tea sporting firm said.

For the first part of this year up to the sale of May 14 the prices have averaged around Rs 105 per kg compared to Rs. 98.80 per kg for the same period last year.

The brokers attributed the favorable price trends partly due to the entry of the CIS countries into our market way.

‘One good thing is that CIS countries seem to have got the taste of our tea over- night and they continue to be the big- gest buyer.

The credit should be given to the government for vigorously promoting our tea in Russia,’ a broker said.

However, industry experts pointed out that the multinational control of the tea industry has prevented the country from getting the best prices for her tea. Buying. processing and international marketing of tea are currently dominated by a few multinationals such as Unilever, Lyons, Tetley, Typhoon, James Finlay, Harrison and Crossfield and Twinnings.

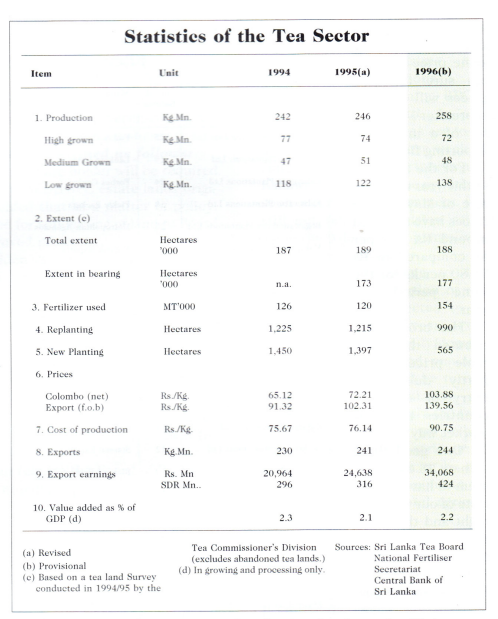

According to the Central Bank Annual Report, tea production continued to increase for the third consecutive year, surpassing the previous year’s peak production level by 5% to record an all time high of 258 million kg during 1996.

According to the Central Bank, during the last decade the tea Industry experts pointed out that the multinational control of the tea industry has prevented the country from getting the best prices for her tea. small holders share in the total output had increased from 39% in 1987 to 57% by 1996. The striking feature of the small holders production is that this 57% of the output had come from 44% of the mature extent under tea which signifies the efficiency of the small holder compared to the large plantations.

The national average yield improved during 1996 by 4% to 1043 kg, which is still well below the average yield of Kenya which is around 2000 kg per hectare. However, the small holder. yields are higher than those of the state sector and privatized company yields by 85%. According to the Central

Bank’s report, the weighted average cost of production of the large plantations increased by 18% to Rs 90.75 per kg owing mainly to the increase in wages during the year.

‘Price recovery, which was triggered off as a result of the re-entry of the CIS countries to the Colombo auction during the latter half of 1995 continued throughout 1996 as well. As a result, the average Colombo auction price surpassed the cost of production for the first time after five years of negative profit margins.

Demand for Sri Lankan tea was further enhanced by the reduction in the exportable surplus of Indian tea because of domestic demand increase in India,’ Central Bank’s Report said.

Rubber production during 1996, estimated at 112 million kg. was 6% higher than the production recorded in 1995.

According to the Central Bank Report for 1996, this was the best production recorded since 1990 while the improvement was attributed to well distributed rainfall coupled with the increased application of fertilizers and better management brought about by the attractive prices prevailing since the latter part of 1994. However, rubber production has shown a declining trend over the years and the present annual production is about 20% less than the production recorded a decade ago.

The report also points out that although in comparison Sri Lanka accounts far less than 2% of the total world rubber production, Sri Lanka is the major exporter of crepe rubber and a leading exporter of industrial tyres.

The extent under rubber has shown a marginal increase and is now 162,000 hectares. However, the extent under tapping had declined by 1% to 122,300 hectares. Therefore, the production increase was entirely owing to an improvement in the yields.

The total extent under coconut Cultivation Board was around 417,000 hectares in 1996.

This was about 22% of the total available land in the country and was second only to the extent under paddy. In 1996, the total extent under bearing was estimated at 363,000 hectares.

According to the Central Bank Report, coconut production was estimated to have declined by 8% in 1996 to 2546 million nuts.

The decline was attributed to the lagged effect of the drought conditions that prevailed in the latter part of 1995 and early 1996. Due to the decline in supply and strong competition for procurement of coconuts for desiccated coconut and coconut oil production, domestic prices of coconuts increased by more than 70%.

Uncertainties about the pro- National Fertiliser Secretariat Central Bank of Sri Lanka duction levels in the Philippines and high price of substitute vegetable oil raised the world prices of major coconut kernel products during the year.

The average export price of the three major kernel products reached its peak, increasing by 55% to Rs 9.42 per nut from Rs 6.08 per nut in 1995. DC fetched the highest average f.o.b. price of US$ 1177 per metric ton which was an increase of 42% over the previous year. Average f.o.b. price for coconut oil and copra in 1996 were US$ 976 per metric ton and US$ 734 per metric ton, respectively. The high prices reflected the tight supply situation in the market and the high quality of the products from Sri Lanka. In 1996, total export earnings from coconut products increased by 12% to SDR 76 million.