Former President Ranil Wickremesinghe.

A Country on its Knees (Mid-2022)

By mid-2022, Sri Lanka was not just in trouble. It was flat on the floor. Fuel queues stretched for kilometers under the punishing sun. Mothers clutched ration books, hoping for a tin of powdered milk. Hospitals ran short of medicine. Power cuts lasted half the day. The nation had defaulted on its foreign debt for the first time in history, with over USD 51 billion in obligations it could no longer meet.

Reserves had withered to barely enough to cover a few weeks of imports. Inflation raced toward 70 percent, the rupee lost half its value in months, and the government openly admitted it could not even scrape together a million U.S. dollars for basic fuel shipments. In June 2022, then-Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe stood in Parliament and gave a speech that stunned even the most jaded lawmakers. “The economy has completely collapsed,” he declared, breaking with decades of political habit of sugarcoating disaster. By that point, he was the lone member of his party in Parliament—a political survivor many had written off. However, within weeks, when protestors stormed the presidential palace and forced Gotabaya Rajapaksa into exile, Wickremesinghe was elected president by Parliament. He inherited not a state in crisis, but a state in free fall. Few expected him to last the year.

Yet, over the next 26 months, he would drag Sri Lanka from bankruptcy toward stability—not through populism but through austerity, reform, and relentless diplomacy.

Sri Lanka’s economic crisis led to severe foreign exchange shortages, hindering the import of essential goods like fuel and cooking gas.

Firefighting in the Ruins (Late 2022)

The new president did not have a honeymoon period. The crisis was burning on every front. Fuel was gone, tourism had collapsed, exports were stalling, and social unrest threatened to ignite again.

Wickremesinghe’s first task was to stabilize the country enough to stop the bleeding. He reached out to India for emergency medical and fuel shipments. He negotiated relief programs with the World Bank and Asian Development Bank. He tasked the Central Bank with aggressive monetary tightening, driving interest rates above 15 percent to choke inflation.

Most controversially, he began raising taxes—VAT jumped from eight percent to 15 percent, then 18 percent; income taxes were lifted, even on middle-income households; fuel subsidies were cut. These were brutal measures in a nation already exhausted. But Wickremesinghe argued there was no other way: “Without revenue, we cannot negotiate. Without negotiation, we cannot survive.”

By November 2022, tentative signs of stabilization appeared. Fuel queues shortened. Inflation, though still extreme, began to peak. Tourists trickled back to the beaches of Galle and Trincomalee.

For the first time in months, Sri Lanka’s headlines were not only about the collapse.

Still, ordinary people felt only pain. Soaring prices ate up their salaries, and small businesses closed. In the streets, resentment boiled: Was Wickremesinghe saving the country—or strangling it?

Ranil Wickremesinghe’s presidency proved a hard truth: recovery from bankruptcy is not a sprint but a grind, and the leader who stops the bleeding is rarely the one chosen to lead the healing.

Sri Lankans protesting in front of the Presidential Secretariat in Colombo.

Ranil Wickremesinghe with Janet Yellen, US Treasury Secretary.

Kristalina Georgieva, Managing Director, IMF in discussion with Ranil Wickremesinghe.

The IMF Lifeline (2023)

If 2022 was triage, 2023 was about setting broken bones. The crucial step came in March: after months of negotiations, the International Monetary Fund approved a USD 2.9 billion bailout program under an Extended Fund Facility.

The first tranche of USD 330 million arrived almost immediately, unlocking further assistance from the World Bank and ADB. But the IMF package was not just cash—it was a blueprint.

Under its terms, Wickremesinghe’s government committed to sweeping reforms:

- Subsidy removal: Fuel and electricity pricing shifted to ‘cost-reflective’ levels. Tariffs shot up. For households, electricity bills doubled. For businesses, production costs soared.

- Tax reform: VAT and income tax hikes became permanent features, restoring revenue after years of politically motivated cuts.

- Central bank independence: A new Central Bank Act insulated monetary policy from political pressure, empowering it to target inflation and regulate banks.

- State-owned enterprise reform: Over 50 loss-making companies, from airlines to utilities, were slated for restructuring or privatization.

The austerity was harsh. But it laid the groundwork for stabilization. By late 2023, the data showed progress:

- Inflation, once 70 percent, fell below six percent.

- The rupee stabilized.

- Tourism rebounded strongly, generating billions in foreign exchange.

- GDP, which had shrunk by 7.8 percent in 2022, grew by 1.6 percent in Q3 and 4.5 percent in Q4 of 2023.

Equally important were debt talks. Wickremesinghe secured agreements with India, Japan, and the Paris Club to restructure USD 5.8 billion in official debt, deferring repayments until 2028–2043. Negotiations with China—Sri Lanka’s largest bilateral creditor—moved slowly, but flexibility signals emerged.

The IMF praised the progress. Yet public anger simmered on the streets. Many households couldn’t afford electricity, and university students marched in protest. For the poor, ‘recovery’ was still a word in government statements, not their wallets.

Ranil Wickremesinghe with Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

Ranil Wickremesinghe and Chinese President Xi Jinping.

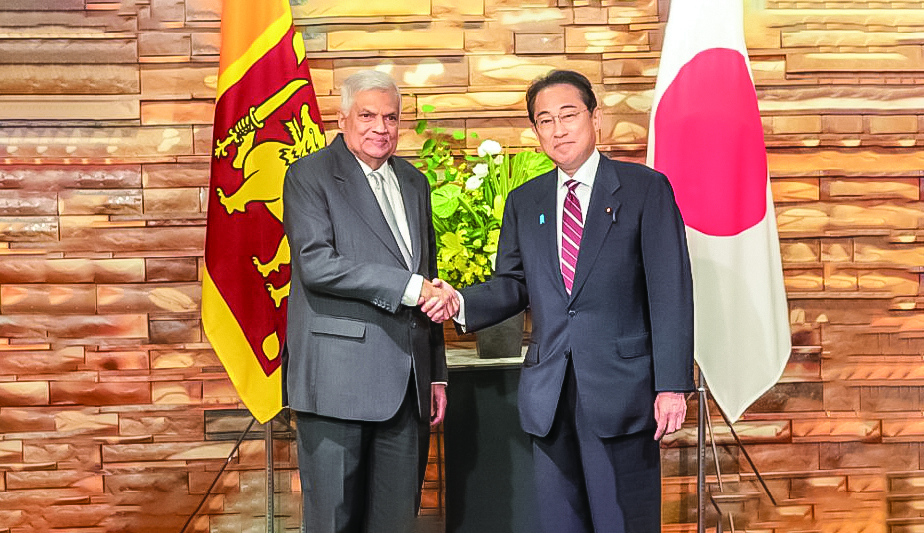

Ranil Wickremesinghe with Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida.

Signs of Life (2024)

As 2024 dawned, Sri Lanka was no longer in collapse. It was climbing out of the hole. GDP forecasts turned positive. Inflation continued to fall, even tipping into deflation by late in the year. Interest rates were unified at eight percent.

Tourism exploded. Over one million arrivals brought in USD 1.5 billion by mid-year. The island’s beaches, tea country, and wildlife parks buzzed again with foreign travelers. New trade agreements—such as a free trade pact with Thailand—signaled Sri Lanka’s intent to plug back into global commerce.

The World Bank projected 4.4 percent growth for 2024, citing resilience in services, agriculture, and remittances. For the first time in years, Sri Lanka’s name appeared in international headlines not as a warning, but as a modest success story.

Still, recovery had winners and losers. Exporters, tourism operators, and big businesses benefited. But ordinary citizens bore the tax hikes and cost-reflective utility bills. Middle-class families saw disposable income vanish. For many, Wickremesinghe’s ‘cure’ felt worse than the disease.

This paradox—macro-level recovery, micro-level hardship—set the stage for the political reckoning to come.

Ranil Wickremesinghe with French President Emmanuel Macron.

Singapore Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong with Ranil Wickremesinghe.

Thailand Prime Minister Srettha Thavisin with Ranil Wickremesinghe.

The Reckoning (September 2024)

By September 2024, Sri Lanka was undeniably in better shape than in July 2022. Bankruptcy had given way to stability. Inflation was tamed. Growth returned. Debt restructuring advanced. International confidence revived. But politics is not measured in balance sheets. Wickremesinghe, a man known for pragmatism more than charisma, faced an electorate scarred by austerity.

Legacy of a Reluctant Savior

Ranil Wickremesinghe left office in September 2024 not as a hero or villain, but as a rarer: a leader who did the hard, unpopular work when no one else could. He inherited a bankrupt nation and laid the foundation for recovery through sheer persistence and technocratic maneuvering.

His legacies include the IMF bailout, central bank autonomy, tax reform, debt restructuring, and tourism revival. Yet he also left behind a nation weary of sacrifice.

The austerity that saved Sri Lanka also cost him power. History may judge him more kindly than voters did in 2024, recognizing that Sri Lanka might not have survived to argue about its future without his steady, unglamorous stewardship.

Ranil Wickremesinghe’s presidency proved a hard truth: recovery from bankruptcy is not a sprint but a grind, and the leader who stops the bleeding is rarely the one chosen to lead the healing.

Ranil Wickremesinghe left office in September 2024 not as a hero or villain, but as a rarer: a leader who did the hard, unpopular work when no one else could. He inherited a bankrupt nation and laid the foundation for recovery through sheer persistence and technocratic maneuvering.

L–R: First Deputy Prime Minister of Spain Nadia Calvino; Dr. Akinwumi A. Adesina, President of the African Development Bank Group; Prime Minister of Rwanda Édouard Ngirente; President of Chad Mahamat Idriss Déby Itno; Ranil Wickremesinghe; President of Tunisia Kais Saied; and Kristalina Georgieva, Managing Director, IMF.

Ranil Wickremesinghe in a friendly discussion with Elon Musk.