UL Pai

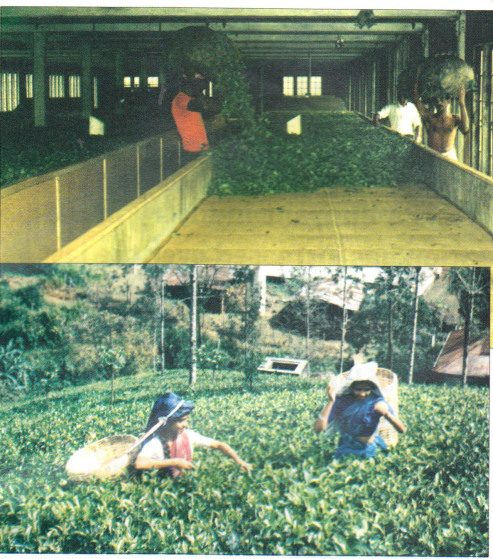

Tea is a buoyant industry in India. This overall realization has increased over the last year. Fall in the Kenyan Tea output translates to better prospects for the Indian Tea exports. But low productivity, non-availability of land, high cost of cultivation and fanning out of investment to non-tea segments, suggest that even the promoters find little going in favor of Tea.

India is the world’s largest producer of tea with an output of 800 million kg. 80% of which is for the home market and has been experiencing strong demands from overseas buyers during the recent months. Every kg sold so far this year has fetched Rs 5 more than in the same period last year. Auctioneers predict that this trend will continue through the rest of the year. Although the quantum of India’s tea exports in 1996 was below the 1995 level, the performance in the current year (1997) may be better, according to J Thomas & Co, the top tea broker.

The reasons for the surge expected this year are many. With an expected fall of 40% in the Kenyan tea output in the current year due to a drought in the first four months of the current year, prospects of Indian tea exports in 1997 have brightened. (Same goes for Sri Lanka also). Of late, the UK buyers are eyeing Indian tea to meet their demand, as prices in Kenya – UK’s established source for tea -have shot up.

The industry is sitting pretty on growing demand and a rise in tea prices during the current year. An average 4.6% rise in domestic consumption as against a growth of about 2.7% in production during the last four years has subdued export growth which has declined by an average 2% a year in the last four years.

The high-growth markets in West Asia are likely to step up imports of Indian tea. Iran re-entered the Indian market and Iraq may also follow suit this year as UN sanctions have been lifted. Better inquiry from CIS, Japan and the continent may also be expected.

One more favorable pointer is that price conscious importing countries may well see India as a useful alternative for sourcing orthodox teas, as the Sri Lankan orthodox prices are currently ruling at an all-time high.

The latest available information points out that in the first quarter of this year, the global tea production has fallen by 35.1 million kg (mkg) to dip to 178.6 million kg compared to the same period last year. And, the fall has occured in all the major producing countries. Kenya has lost a maximum of 25.9 mkg to produce 44.1 mkg. Indone- sia lost 3.3 mkg to dip to 20.3 mkg. Sri Lanka lost 2.2 mkg to turn out 38 mkg. The marginal increases of 0.9 mkg in Malawi to reach 17.8 mkg and 0.2 mkg to reach 4.4 mkg in Zimbabwe are too inadequate to make good the sizable loss elsewhere. In India, the overall production this year was 54 mkg against 58.8 mkg last year in the same period. Still there is a difference in the crop loss in India and the rest of the world as far as its impact on the market and price is concerned. In countries such as Kenya and Sri Lanka, almost the entire produce is exported, the retention for domestic market being minimal. That also means, a number of countries are dependent on the supplies from these sources. So, when the supplies dry up they are forced to look for alternative sources such as India.

which have come into its fold? This is a necessity, because, if it does not take steps to hold them under the umbrella, the day the crop prospects improve in Kenya, Sri Lanka or other countries, the importers would return to them. So, India would remain only a substitute market for them, not a stable one.

A closer analysis reveals that India is not fully geared to tap this potential. The Tea Board of India has set a target of 1000 mkg by 2000 AD. This target was set some- time in 1993 and entailed a seven- year plan to raise production to meet the projected domestic de- mand of 705 mkg and to increase export to 295 mkg by the turn of the century. The target for the year 1996 has been almost met with the total output 780 mkg. But according to industry sources, the production is unlikely to touch the magical figure of 1000 mkg. Taking into account current production, the industry would have to produce an additional 50 mkg a year but it was a tall order due to various reasons. One of the reasons for the skepticism was that production had reached its potential especially in South India and there was no additional land to extend tea cultivation. If the target had to be reached, then there was a need to plough back profits for development. But with the input costs increasing and margins shrinking, coupled with higher rate of agricultural income tax in the southern states, this was a tough task. However, the increase in yield per hectare in the northeast regions in India, where yield was low compared to South Indian standards, and remunerative prices may help achieve a figure near to the target.

The problems galore in the Indian tea industry are in fact more deep-rooted. The basic reason for the sluggish trend is the non-availability of land. And non-availability of land for development of new plantations has been the resultant

effect of both government policy and industry conservatism. Land area under tea cultivation in India stands at 0.42 million hectares (mn ha), second only to China with a land bank of 1.3 mn ha. However, it is hardly a matter of comfort as India records one of the slowest growth takes in terms of expansion of its bank. In the past decade, hectarage under tea has grown by just 5.9%. In Kenya, the area under tea cultivation has grown by almost 32% over the past 10 years. Same is the case in Indonesia.

With land acreage not keeping pace, there is an urgent need to increase productivity. However, Indian tea producers have been lacking in this aspect too. One of the major bottlenecks preventing the increase in production and productivity is the age of the Indian tea gardens. Currently around 80% of Indian bushes are over 30-years- old, 45% are over 50-years-old. Among most of the competitor countries the average age of tea bushes is around 30-35 years, which in turn reflects a higher pro- ductivity. Also replantation has been sluggish. The annual rate of replantation stands at only 0.4% as against 3%. The main reason for the slow pace has been the lack of capital investment required for planting new bush and the gestation period involved in getting production from the new bush. Re-investment dries up and capital gets diverted. The very fact that no foreign capital has been attracted to the tea industry after the economic liberalization is proof of the assessment that there is no money in it.

However, the government is taking steps to give a helping hand to the industry by getting finance from the World Bank. Further, the government is also implementing certain reforms in taxation, which will provide some assistance to the industry. Other remedial measures from the state governments will also improve the prospects of the industry in the coming years.