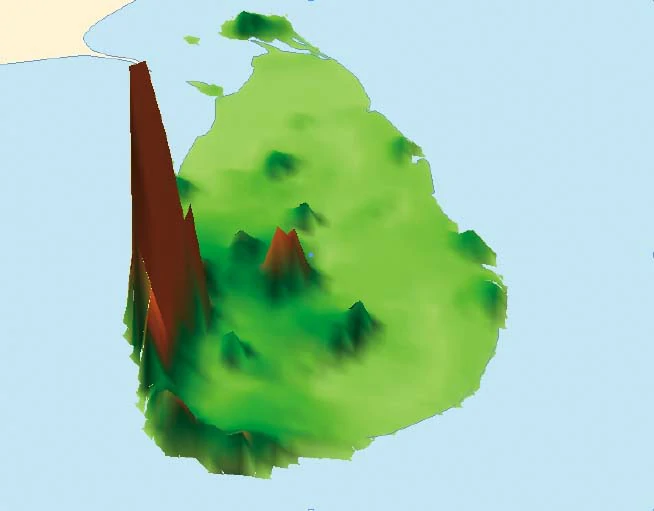

The focus of the World Development Report 2009, Reshaping Economic Geography is the spatial transformation of economies needed for progress. This can be measured as changes in three dimensions – density, distance and division relating to human, political and physical geography, respectively. Rising densities, reduced distances and fewer divisions are the essential prerequisites for progress. Sri Lanka is well placed to continue these transformations, due to its institutions for social service provision, its entrepreneurial people, and its geographic location.

The World Bank team headed by the Director of the World Development Report 2009 and Chief Economist, Europe and Central Asia, Dr Indermit S Gill was in Sri Lanka recently to discuss the findings of the report and present the main recommendations to the country. Dr Gill took time off from his busy schedule to unravel the core of the World Development Report with Business Today.

By Udeshi Amarasinghe | Photography by Menaka Aravinda

What is the focus of the World Development Report 2009 and what is the reason for this?

The aim is to examine the influence of geography on development. What does good geography mean? What does bad geography imply? We look at how countries can move from bad to good geographies. The focus is not only on physical geography but also on human geography and political geography. Though you cannot easily change physical geography, nations can actually change their human and political geography. We use an economic geography framework to assess the influences of human, physical and political geography.

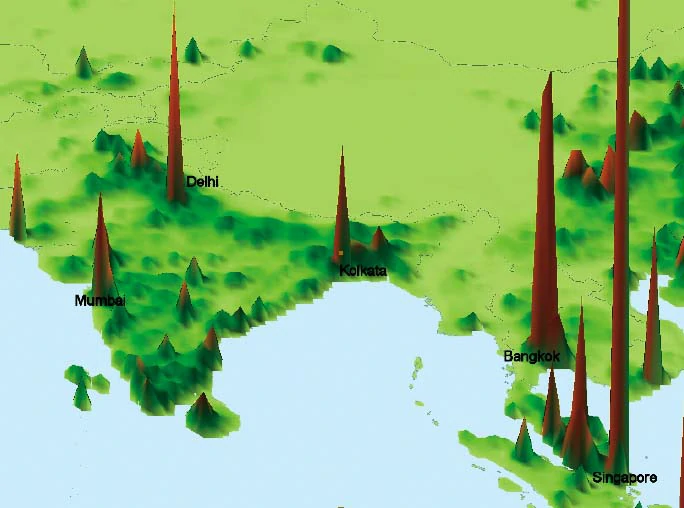

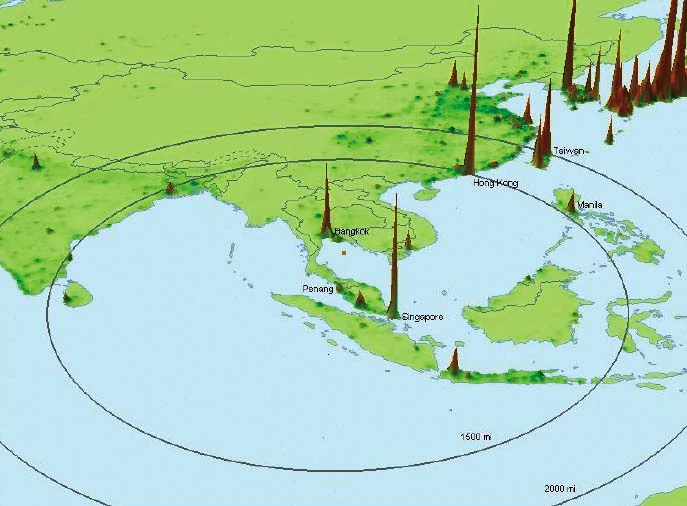

Another way to look at it, is to ask: what are the changes countries need to make in order to prosper, that is, to move from low to middle income as Sri Lanka has over the past few decades, and then to high income levels? One important aspect of human geography is the move to cities or urban agglomerations such as Colombo. Another is longer distance migration from places that are not doing too well, to places that are doing better. In Sri Lanka, for example there is migration to the Western Province from the other areas. The third aspect is not so much the movement of people but the movement of services and products through trade. This relates to how open countries are to foreign trade, which in turn relates to how specialised they become.

We feel that these changes can be captured and measured. In the World Development Report these changes are measured in three dimensions of economic geography; the dimensions are density, distance and division. Our aim was to show countries transform along these three dimensions. Countries that are more developed actually have higher densities, shorter distances and fewer divisions.

What makes World Development Report 2009, different from previous World Development Reports?

In the past, we’ve focused on what countries produce and how they produce these things. Economists didn’t look at where such activities happen, or the best location for production. But this aspect is very important, because it may be the hardest to get right, and then to change if you haven’t. That is what is new about the current report: we recognise the importance of the location of activity. This relates closely to some of the debates that you hear in Sr Lanka. Is Colombo too big, and shouldn’t Sri Lanka have other cities of equivalent size? Is it good for the country to have migration between different parts of the country? What are the best ways for Sri Lanka to connect to world markets is it through regional markets or world markets or through a combination of the two, depending on the goods that you produce? These are important debates, and they are often quite polarizing because the stakes can be high.

Sri Lanka Has Done Well In Providing Social Services Everywhere, Therefore The Foundation For An An Efficient Urbanisation Has Been Laid.

What are the key findings of this report?

We tend to focus too narrowly on places that are not doing well the villages, the lagging provinces, and the most unfortunate countries. The reality is that what is key for development is the interaction between places that are not doing well and those that are doing better. When you focus on these interactions, you find that you don’t see big agglomerations such as bad things, you don’t see migration from lagging areas as a failure of policy but as the desire of people to get nearer to prosperity, and you don’t just see the risks that come from specialization and trade but also the considerable rewards that they bring. Agglomeration, migration, and specialization these are words you see a lot in the report, because we find that they are the forces that power nations to prosperity.

We tend to think that as countries get richer, activities bcome more dispersed and people don’t need to move to access better opportunities. What we find is the opposite: activities become more and more concentrated, and mobility becomes progressively more important, not less. But we also find that the most successful countries disperse social services widely, ensuring that people have access to security, schools, streets, and sanitation.

Another way to think about this is to contrast two equally sized countries, say China and the United States. In China, before its rapid growth over a quarter century, if you travelled from east to west, you would have seen a fairly flat geography of economic production most people would be in agriculture related activities – but a very bumpy geography of social welfare, with basic services reasonably widely available near the coast, but not in the interior. In the US, if you travelled from one coast to another, you would see the opposite. You see a very bumpy geography when it comes to economic production as places specialize but a very flat geography when it comes to social welfare, since basic services such as education and health are widely accessible all across the US.

You actually want a greater concentration of economic production in a few places because you get economic efficiency that way. You need greater social services to be dispersed, because you get more social justice and stability that way. Basically the main implication of the report is that policy makers have to distinguish between the geography of economic production and geography of social welfare. If you have both a bumpy geography of production and a flat geography of welfare, you get both efficiency and social stability; you get economic development.

Talking about density in cities and urban migration, not only in developing countries, also in developed countries, we find that the highest concentration of poor are also in these areas, how does this report tackle the issue of urban poor and slums?

In this report, we look at why this problem exists and it is due to a fairly straightforward reasons: this transformation of countries from largely rural to urban, takes place fairly early in their development. It takes place roughly in the per capita income range of $ 300 to 3000. A country that has a per capita income of $ 3,000 is still a low middle-income level country, but it has often become highly urbanised. Sri Lanka is in the middle of this transformation, and can expect a rapid move to cities. The problem is that countries are not often prepared for this transformation, institutionally or financially. In fact, there is no alternative. Governments need to prepare the cities for an influx of people; it is futile and undesirable to try to stop or stem this flow, because it reflects the transformation of economies from agriculture based to industrialised economies. It is necessary for development.

What is the best way to prepare? Start by providing a broad foundation of social services, good land reform, and fluid labor markets. Then, more selectively, examine the infrastructure needs and invest in connecting some places to others. If these two things are done, the issue of slums and urban squalor will be a minor one. If not, you’ll get a proliferation of slums. A good example of this, is the city of Mumbai, which did not do so well in terms of land markets and infrastructure investments. Today, more than half of the city’s population lives in slums, made famous by films such as ‘Slumdog Millionaire’.

Rural-urban migration should be driven by a ‘pull’ factor – the lure of jobs in the city – not a push from villages because of a lack of basic services in rural areas. Therefore you need to provide social services everywhere. Sri Lanka has done this well, and so has laid the founda-tions of an efficient urbanisation. It does not need to be afraid of growing cities and towns.

In reality isn’t it more like a trickledown effect than a pull?

It depends on what reality you are thinking of. If the reality is one in which you leave every thing to the market, then that would be the effect. In an economy where there is a good balance between market forces and government policies, you actually end up not having a trickle down but the services going out fairly early in development. For example, there are countries like South Korea and Costa Rica that have done this rather well. They ensured that social services reached the entire population fairly early in development. So people migrated when they were ready to take on the challenges of city life and compete for better jobs. They migrated at the right time; they neither left early nor late. Every successful country needs a more inclusive and efficient urbanisation the result is a “bubble up” rather than a trickle down.

Since you mentioned South Korea, the country had more protectionist policies at the beginning prior to liberalization and they have done very well. Considering this, why is the report encouraging more global integration at an early stage of development?

Countries actually become ready for globalization fairly early in their development. For example, even Cambodia, at a fairly early stage in development, is actually participating actively in global and regional trade networks. A country doesn’t need to be wealthy or institutionally advanced to integrate with bigger markets; indeed, poor countries have to integrate. The reason is quite simple: for a late developer, growth strategies have to be outward-oriented because markets are no longer within that country, they are elsewhere. Even big countries such as China realise this. As a country gets smaller and smaller its domestic market gets smaller as well. Such countries have to access the world markets. Countries like India, China and others have accessed these markets elsewhere.

Sri Lanka’s garment manufacturing has benefited Sri Lankans too, because they get cheaper garments now, but it was driven by the scale made possible by accessing foreign consumers. The best way to do this is for countries to have thin borders – you can’t change the physical distance to world markets but you can change the economic distance, both in terms of transport policies and trade policies as well as policies that make the investment climate in Sri Lanka better. That is important because, not only do you get to access markets but also to encourage foreign investors in order to acquire their knowledge on how to produce, as well as sell their goods. If you do that well then you essentially pull in foreign knowledge of products, processes, and markets. Without this, you cannot easily access those markets.

Some may argue that through such policies the rich countries get richer while the poor get poorer. What is your response to this?

I feel that greater trade has not led to impoverishment. Trade has always led to advancement. It helps the poorer nations, and it helps the richer countries. But that is the most sustainable way to engage – developing nations should not rely on the charity of others. You want to rely on the self-interest of others and your own self interest. It is more sustainable to have it like that. Even during bad times, sensible policymakers realise that you shouldn’t risk the imports from poor countries because consumers actually benefit a lot more.

We Think That Sri Lanka Has Laid The Foundation Of Progress. All Of These Will Need Transformations Along The Three Dimensions Of Density, Distance And Divisions. Sri Lanka Is Well Positioned To Make This Change.

In that case, how would you describe the situation in Africa?

Due to human, political and physical geographical problems, the issues in Africa are particularly tough. Africa is where you get a confluence of low densities, long distances and deep divisions. In the report, we say that development in Africa faces a three dimensional challenge. You need to do more when the problem is in all three aspects, than in places where the dimensions of the integration challenge are fewer. As these dimensions increase we need to do more and more and more.

We do say you do need these common institutions that is needed to put in place with social services. You also need infrastructure because it is a very large continent. Unlike other parts of the world, Africa does not have natural bodies of water like rivers that connect the continent. Africa needs a special deal in terms of trade, such as AGOA – African Growth and Opportunities Act, which is the way USA trades with African countries. We feel that there are good ways to do that. However in Africa, due to its fragmentation – 50 countries that are each not very large, the economic map in the sense of regional integration of Africa is especially important. National institutions and national infrastructure need to be provided as regional infrastructure and institutions because of the fragmentation of Africa. Furthermore, there isn’t a big country in the continent, in which countries can access world markets. One potential country is actually South Africa; another potential country was Nigeria. In other parts of the world, you have the Brazil, Mexico, India and China from which you can access the world market. In Africa this is a problem.

In Africa including the landlocked countries, there has been a big push to develop education and health. That is the right thing to do. There was also a push to spread infrastructure to all of these places and that has not proven to be the right thing. Infrastructure had to be concentrated in parts of Africa where you would try to generate the pull. There is a lot of push in Africa but not pull.

What are the sources of information for the World Development Report? Since all countries do not have a uniform method of collecting such data, how have you overcome these discrepancies?

We use economic history, statistical analysis and case studies. In the first part of the report, we actually go back in time, approximately two-three centuries to actually obtain as much numerical evidence as we can, to see how those three dimensions have been transformed. For the second part of this report that actually looks at why these changes took place, we actually used academic work that has been done over the last two to three decades. We used the analytical work, the theoretical insights of people such as Paul Krugman, who was awarded the Nobel Prize for Economics last year. In the third part we actually looked at the policy experience through case studies of countries that have overcome these challenges. Thus, we looked at all three – historical, analytical and more contemporary case studies.

We used geographical information on what has happened over the last decades, as there has been advancement on geospatial information through satellites. We were able to obtain accurate information about roads, networks and human concentration. Let me give you an example. It is hard to compare urbanisation ratios between countries. Everybody uses their definition of how large a city has to be or how large a settlement should be before it is called urban. We have a common definition that looks at how densely populated a square km is, and the proximity of a place to a large settlement. When we talk about proximity we mean, say, 1 hour’s driving distance. Now the distance travelled in an hour can be very different depending on the quality of the road. But we now have a fair amount of information on the quality of the roads as well. Based on these calculations, we find that about one in every three Sri Lankans can be considered an urbanite; the official statistics puts this closer to one out of every seven. A big difference.

The ground situation in each country is different. Considering the recommendations of the report, it would not be applicable to all countries – one model doesn’t fit all. What are your thoughts on this?

You are absolutely right. We not only say that recommendations are not applicable uniformly between countries but also within a country. Therefore you cannot say that what is good for the Western Province is going to be good for the Eastern Province. Thus in the World Development Report, we focus on the provinces as well. In a province that is rural, we say to focus on institutions; in provinces that are rapidly urbanising, we say that they need to build institutions as well as infrastructure. Similarly when we look at a country, we have policies suitable to each context, for poor and sparsely populated, we have one set of policies; for a province that is prosperous and densely populated, we have another.

Similarly, we take to another level and look at the region e.g. South Asia – countries in this area should have policies that would encourage integration with the rest of the world. As human beings, we have a tendency to focus on places that are not doing very well. We worry about how we can help. In reality, you actually see that the places that prosper are those that are connected to successful countries. I’ll give you an example, if you focus on a place narrowly as not doing well, you will try to push economic activities on this country adopted from another. If you zoom out a bit and look at the relationships, you will realise that it is not detrimental if the other place prospers – as long as this place is connected to it. The connection should be through trade, flow of ideas, goods and services, and the flow of people.

When you start to look at the forces of agglomeration, migration and specialisation, they play a very important part in the development of countries. These forces have been studied over the last few decades and we try to distil the essence in the global report in a way that is useful for people who are interested in formulating policies.

How important is this report to Sri Lanka?

Immmensely. It is so important that we are actually compiling a report that will be tailored for Sri Lanka. All of these three debates on urbanisation, regional development and international integration are live debates in the case of Sri Lanka. One cannot say which way these will go, but we know we should have good answers to these questions. What is the role of Colombo in Sri Lanka’s development? What is the role of the other cities? How can one best integrate a country in economic terms? How can the Western Province be integrated with other parts of Sri Lanka? How can we make sure that while the Western Province prospers, the country has a set of policies that helps to share the benefits of this prosperity with other parts of the country?

People may move to the Western Province or they may not. Then the next step is how can the Western Province connect Sri Lanka to the rest of the world. Not in a way that it gets disconnected from the other provinces but in a way that you have a good blend between domestic integration and international integration. We think that the next report will bring out something more specific on the institutional priorities, the infrastructure priorities and then perhaps some ways to actually intervene more closely in a more geographically specific way.

How does Sri Lanka fare in this current report?

We were actually limited by data for certain parts of the country, where we were unable to access data. We couldn’t be as confident of Sri Lanka as we could in the case of some other country. But, let me tell you where Sri Lanka has done very well. I mentioned the geography of social services need to be very smooth and the geography of economic production has to be smooth over time. You need to start this process with the levelling of social welfare. In order to prevent greater imbalances in term of opportunities, you need to spread out those opportunities fairly early in terms of these basic services. From all indicators Sri Lanka has done remarkably well in that sphere such as the dispersion of education, basic healthcare, basic infrastructure including water and sanitation etc. Sri Lanka has done very well. Therefore Sri Lanka is well placed to take advantage of the next round of prosperity in the world and the region. The prosperity will involve these geographic transformations that I was talking about, i.e. greater movement to cities and towns.

We think that Sri Lanka has laid the foundation of progress. All of these will need transformations along the three dimensions of Density, Distance and Divisions. Sri Lanka is well positioned to make this change. We feel that the report is very important because Sri Lanka is now a low middle income level country. Considering the resources of the country such as the human, physical and geographic resources, there is no reason why Sri Lanka shouldn’t be ambitious and strive to achieve the rank of high income earning countries. We think that the basic institutional infrastructure has already been laid.

What was the response of the economists and Sri Lankan policy makers to the report?

We had excellent discussions of the report in Sri Lanka. The main criticism was why we hadn’t compiled the report earlier – perhaps the best compliment a writer can receive. We were humbled by the praise. Obviously not all comments were positive. There were criticisms that environmental and social factors need to be included in the report, factors such as climate change. We also felt we had to be responsible in the sense, though we know that the world is different today, when countries get richer, there are some fundamental features that will always be the same. Those are what we emphasise at the end higher densities, shorter distances and fewer divisions. We feel that some of these aspects are more important today, because of changes in technology, greater number of borders in the world, and the larger share of trade in economic production.

Did any policy decisions come out of this meeting?

Minister Sarath Amunugama gave an excellent opening address, where he did an excellent task in presenting both the pros and the cons of the report. One big outcome of the meeting was that we were able to connect with a group of people who were well versed on the contents of the World Development Report 2009 and also to keep them informed that we were doing more by compiling a specific report for Sri Lanka. We intend to acquire the expertise of this group in writing and reading of the report at the early stages to get their feedback. Naturally, we must use the collective wisdom of Sri Lankans in any report for Sri Lanka. That will actually lead to more specific and practical recommendations for Sri Lanka.

Policy decisions will always take time in a democracy but such deliberation is necessary. We hope this World Development Report will help the people and policymakers in Sri Lanka reach new economic heights.