The Ceylon Association of Ships’ Agents or CASA as it is known was formed in 1966, to replace the Ceylon Shipping Committee appointed at that time, to regulate vessels that called at the Port of Colombo during the 2nd World War. Until August 1995, the association was known as the Ceylon Association of Steamer Agents. The noun ‘Steamer’ used in the good old days was dropped to keep in line with current trends in shipping and ‘Ships’ took its place. However, since ‘Ceylon’ facilitates the use of the abbreviation CASA, it was retained.

Among its numerous objectives, CASA effects an interchange of ideas, information and business methods as a means of increasing the efficiency and use fulness of its 91 members. In pursuing these objectives CASA makes representations to the Ministry of Shipping, the Sri Lanka Ports Authority (SLPA), Customs, Exchange Control and other related institutions. It also acts as a channel of communication between its members and these institutions. Membership of CASA is confined to Shipping Agents in Sri Lanka.

Foreign share holding in the local Ships’ Agency Companies currently stands at 40%. Attempts to increase this further in the recent past were strongly opposed by CASA. “In high technology areas and industrialized businesses you definitely need foreign investors to come in, but in the business of ship agency that is not necessary. CASA feels that we should not have liberalised foreign investment in ship agency because it can easily be done by Sri Lankans”, says M Faizer Hashim, Chairman of CASA. The Minister of Shipping & Ports at a meeting with CASA in March 1996 assured that his Ministry in particular, would not entertain any proposals to increase foreign share holding in ship agency companies beyond the present 40%.

Over the years, CASA has enjoyed cordial relations with the Ministry of Shipping, the Ports Authority and the Customs and has stood the test of time to serve and service trade and shipping alike. CASA has positively answered both causes and especially the government’s call in looking towards industrial growth, says Hashim. He goes on to say that the authorities have been very receptive to CASA’s thinking, “because we face the brunt from our principals when their ships come into Colombo and face delays and low productivity”.

The Port of Colombo has a staff of 17,000 says Hashim as against 4000 in the Port of Singapore. In 1995 Colombo-handled 1,049,000 containers and upto October ’96 the figure rose to 1.2 million with an expected target of 1.3 million to be achieved by December ’96. Singapore on the other hand achieved 12 million TEUS (Twenty foot equivalant units) with a staff of only 4000, “so we are over-staffed and this cost has to be borne by the port which then passes it down to the port user, the shipping community, the importer and the exporter.”

Despite the Port of Colombo being underutilised in terms of capacity (which is capable of handling upto 1.6 million TEUS) congestion in the port is a regular occurrence. “In terms of normal supply and demand economics, if you’re less by about 300,000 TEUS, you should be in a position where ships can come in and discharge their cargo without having to wait as much as 20 hours”, says Hashim.

Colombo is heavily dependent on transshipment. volumes, therefore it’s vital that the best of services and encouragement be given to transshipment operations.

Infrastructure is yet another bottleneck at the Port of Colombo. According to Hashim, the berths have been built without looking at the entrances first, “it’s like building a garage and not looking at the gate. After constructing the berths, they started to dig the entrance channels. Then the Ceylon Petroleum Corporation was allowed to put in their mooring buoy (floating terminal) outside, for tankers to come in and discharge the oil. They allowed the pipeline that leads to the refinery to be sunk through the Northern entrance to the port at a depth of 15 metres. Now, ships with a draught of over 10 metres cannot enter through the Northern entrance.”

Today’s modern vessels are said to have a draught of 12 to 13 metres, therefore these ships must now enter and leave through the South Western entrance to the Port. Hashim says the more appropriate method would have been for ships to enter through the Northern entrance and leave through the South Western channel. “A ship which comes in with about 2000 containers must first discharge her cargo and leave in order to allow the next ship to come in. So, the time lost between these two movements is about four hours of productive time.”

Another oversight in the planning stage has been in the installation of equipment. Hashim says that JCT 3 & 4 terminals have been equipped with gantries costing millions of rupees to service the newer larger vessels which however cannot come into the port, “these are the logistics that have been overlooked in the planning stage”, he adds.

CASA has been extremely vigilant in matters relating to the industry since it is a body of members actively involved in day-to-day ship operations. Therefore, it is they who must be answerable to their principals when reporting back on the happenings in Colombo.

With about fifteen main lines having formed into shipping alliances and consortiums, the number of vessels which each line calls at Port has been greatly reduced. Hashim says that this in effect is a cost reduction technique they’ve come up with, where they operate jointly, thereby each line not having to put in a ship each. Colombo, he says, is missing out on the largest of these consortiums-the Global Consortium which consists of five lines. Although the problem with berths and draughts were solved after CASA made much noise about it, the Global Consortium is still watching the situation in Colombo, “they had planned to come here in 1996 but now they’ve postponed it to 1997. They want to see the performance of the port in terms of delays. They cannot afford delays because their entire service falls back”, he adds.

However, of late, there has been an increase in the number of lines calling at Colombo, “I would attribute that to the fact that Colombo is the best Port in the region next to Singapore and also the fact that India is producing large volumes of cargo now, but Colombo has not been able to capitalise on this and take maximum advantage. We are capturing only about 20% of India’s total exports. We should try to achieve at least 40%. Colombo is ideally located for this Indian cargo to move through and the main line operators will find it cheaper to pick up this cargo in Colombo. This is also an added advantage where buyers are concerned”, says Hashim.

Commenting on the level of productivity he says, “today, in the port, nothing works unless you pay. The level of productivity today is because the agents are paying for every move of the box”. He also says that this payment is now legally accepted and cannot be termed a ‘bribe’ but rather a ‘productivity incentive’.

He believes that the solution to the problem of low productivity could be through the introduction of a proper incentive scheme for performance and attendance with stepped up supervision on performance.

On the proposed development of the Queen Elizabeth Quay (QEQ), CASA claims that it came to know only through the media that the government had is sued a Letter of Intent (LOI) to South Asia Gateway Terminals (Pvt) Ltd., which is supposed to be a joint venture consortium of four companies for the development of QEQ/QCT at the Port of Colombo. CASA in principle, is in favour of the QEQ development project on a Build Operate Transfer (BOT) basis, as competition will lead to efficiency and enhanced productivity in the Port of Colombo. “According to CASA, Colombo requires development because we’re very well located and we’re going to be in the running for the Indian transshipment cargo in time to come. India is not developing her ports as much as expected and lines would prefer to come to Colombo than to the Indian Ports because of the deviation costs”, explains Hashim.

CASA has urged the government to give serious consideration to its concerns and suggestions with regard to the proposed development of QEQ. For instance, the water basin area of the port will be reduced which may further restrict the manoeuvering of vessels, “we understand that the P & O proposal is not to expand outwards. but to contract inwards which means they are going to extend 100 metres into the water basin area from the QCT inside the port. What we know is that presently, big ships cannot come into the port at once. They have to be turned around inside the basin of the port for berthing and sailing. So if you take away 100 metres from the present basin, the question is whether these movements can be done on a safe navigational basis”, says a concerned Hashim.

CASA also hopes the government will ensure that the development programme is not limited to QEQ but extended to the outer harbour development, envisaged in Stage 2 of the proposal.

As a port user Hashim welcomes the excess capacity which the development project will bring about, but what most in the shipping community fear is that the Port of Colombo might lose its status as a common user port. CASA insists that the development of QEQ should not lead to providing virtual terminal status to a few shipping lines only. Even in developed ports such as Singapore, the need to maintain multi-user terminals has been accepted.

CASA also suggests that adequate capacity with deep draught should be provided to service Break-bulk vessels displaced by the development. The North Pier development may be able to absorb part of the Break- bulk volume displaced at the QEQ, but its development must be accelerated in order to provide the required Break-bulk capacity as soon as possible.

Another area that needs to be ensured is that the port maintains capacity ahead of demand. Increasing volumes without corresponding increase in productivity will only lead to aggravated port congestion, thereby stifling plans for the Port of Colombo to realise its vision of becoming a major hub in the region.

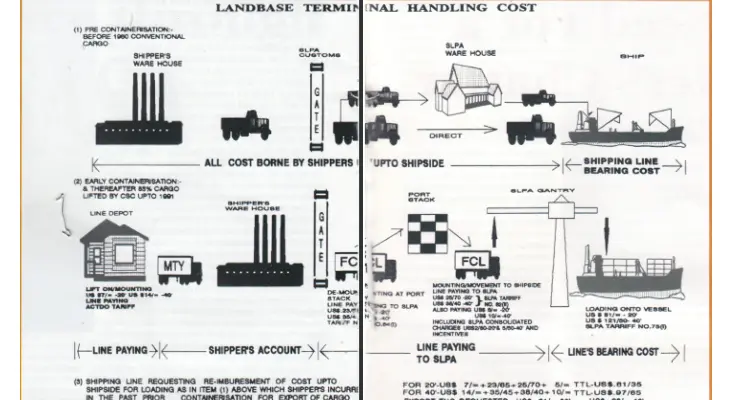

A significant move made by CASA was to introduce a Terminal Handling Charge (THC) for local export containers. The introduction of this charge had been somewhat unconventional in the local shipping scenario and had been a matter of debate for many years. This long delayed THC was not pursued earlier due to the need to encourage Sri Lanka’s exports. However, with the rapid changes that have taken place since the liberalisation of shipping, the drastic reductions in ocean freight and the need to maintain conformity with recoverable charges such as the THC according to the international shipping convention, CASA finds it no longer possible to delay the introduction of this charge. CASA therefore has decided to introduce the THC for export containers as follows:-

US$61.00 for a 20′ container

US$98.00 for a 40′ container

US$122.00 for a 54″ container US$6.00 per freight ton of LCL cargo This decision by CASA has been a bone of contention between the association and the Sri Lanka Shippers Council. CASA says that what the lines are trying to achieve from the THC on export containers is a partial recovery of the actual shore based cost. According to Hashim, Sri Lanka is the only country where there has not been a THC for ex the land based cost of landing the cargo to have it shipped out. The THC on the importer’s side which is the cost of landing the cargo and moving it out of the port has been borne by the importer for the past five or six years.”

ports in the past. “In every country the exporter pays the THC which is Before liberalisation of shipping, the Ceylon Shipping Corporation (CSC) was the major operator in containerised cargo. Not only did it enjoy the monopoly at that time but also a lucrative sup ply of cargo as well as high rates, “so the CSC finding that the freight rate earned off a box was so high, didn’t mind paying the THC, but after liberalisation in 1990 and almost every line calling Colombo, the market rate per box started to slide down. Today, with the consortiums and alliances the competition is so severe they are actually fighting for the cargo”, says Hashim.

In conclusion, commenting on the relevance of a professional qualification to operate a shipping agency business, Hashim says that professionalism is most welcome because it widens the exposure and vista of the individual or an employee, but it’s the person’s dedication and capacity to absorb which ultimately matters.