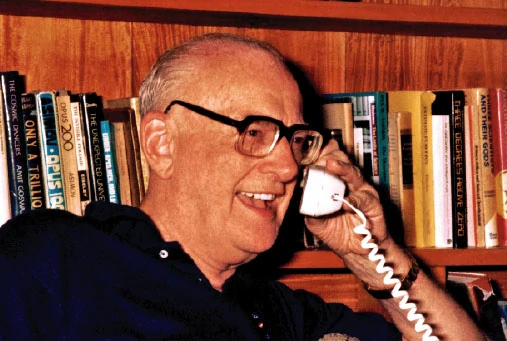

Sir Arthur C Clarke, who made a career out of being unpigeonholeable, was fond of defining intellectuals as those educated beyond their intelligence. He might therefore not like this label, but Sir Arthur was a courageous and relentless public intellectual all his life – one who engaged in rational discussion and debate on a wide range of subjects in the public interest.

By Nalaka Gunawardene

mages by Shahidul Alam and Rohan de Silva/p>

It was his deep personal commitment to the public good that prompted Sir Arthur to get involved in discussions covering topics ranging from renewable energy and telecommunications to coast con-servation and disability rights. He didn’t get involved in these mostly local issues to enhance his already well-established global stature. He could easily have stayed aloof of such discussions and occasional controversies, and led a secluded life in the comfort of his Cinnamon Gardens home. But he chose not to – and Sri Lanka is richer for it.

Indeed, he often brought his considerable authority and gravitas to bear on the causes he championed. He was aware that entering the public sphere exposed him to potential criticism. He once told me in an interview: “A guest must be careful about what he says of the host: contrary to popular perception, I am not a Sri Lankan citizen – only a resident guest. Yet, having lived here for 41 of my 80 years, I now regard this alone as home, and have visions and hopes for my adopted land.” (‘My Vision for Sri Lanka in 2048′, The Sunday Observer Magazine, 14 December 1997).

“Two of the greatest evils that afflict Asia, and keep millions in a state of physical, mental and spiritual poverty are fanaticism and superstition.

This caution notwithstanding, Sir Arthur never hesitated to enter a fray. While he always spoke with the courage of his convictions, his was essentially a voice of reason and moderation. And although he firmly stuck to core principles, he remained open-minded and willing to hear out others’ opinions and arguments.

Sir Arthur’s contributions to Sri Lankan public life spanned for over half a century he lived here (1956 – 2008), and covered several spheres including science and technology, higher education, arts and culture, mass communication and environmental conservation. While he held some institutional positions part of this time, he was more effective simply as Arthur C Clarke the respected and valued global brand.

How much and how well Sri Lanka benefited from the ideas and advice Sir Arthur offered so generously needs separate assessment. Meanwhile, tracing some highlights of Sir Arthur’s role as a public intellectual in Sri Lanka provides insights on factors and processes that shape public policy and discourse in our ‘Land Like No Other’.

As Sir Arthur summed up in 2005: “During the time I lived here, I have seen my adopted homeland advance in various ways, but sometimes it has taken wrong turns. If we have the humility to learn from past mistakes, the next half century can be far better than the last.”

Vision for a better Sri Lanka

If Sri Lankans feel their country lacks a long term vision, they could go back to the substantial volume of writing and public speeches that Sir Arthur left behind. Here is a typical piece of advice to business: “We must exploit our comparative advantages – such as the high literacy and technical dexterity of our people; the geographical location and medium size of our island. In a nutshell, Sri Lankans should not just work hard, but work smart in the global marketplace. We have to evolve our own business and technical models.”

Sir Arthur saw both the macro and micro, and connected the two in his mind. He watched with concern how Sri Lanka’s population doubled in half a century, and how the once idyllic island was torn apart by ethnic strife and ultra-nationalism. Managing human numbers and accommodating human diversity were among the biggest challenges he saw.

Having already achieved impressive social indicators in health and education, Sri Lanka’s future need was “not so much to add years to life, but to add life to years,” he said. Future economic development would have meaning only if it is socially and environmentally sound, and the benefits were shared more equitably, he emphasized.

For him, equality stretched beyond sharing material benefits to include the right and opportunity for everyone to live with dignity. In the last two decades of his life, he repeatedly called for tolerance, reconciliation and harmony among ethnic and religious groups who call Sri Lanka home. “We should not allow the primitive forces of territoriality and aggression to rule our minds and shape our actions. If we do, all our material progress and economic growth will amount to nothing,” he cautioned.

Sir Arthur didn’t glibly speak about peace; he constantly called for ‘lasting and tangible peace’. He believed that “peace is not a condition granted or secured by agreements; it is a state of mind that we all need to cultivate”.

British-born and calling himself an “ethnic human”, Sir Arthur had strong views on war and peace that could be traced back to his youth when he served in the Royal Air Force during Second World War. As a radar officer, he was never engaged in combat, but had a ringside view of Allied action in Europe. An avowed pacifist for much of his life, he was fond of saying, “I’d like to think that we’ve learnt something from the Twentieth Century – the most barbaric period in history.”

He chose strategic moments to renew his plea for resolution of the Sri Lankan conflict, e.g. the golden jubilee of independence (1998), the Asian tsunami (2004), and his own 90th birthday in December 2007 – when he cited peace in Sri Lanka as one of his three last wishes.

In the days following the devastating tsunami, Sir Arthur shared our optimism that the calamity might finally bring all combatants to their senses. In a widely published essay on the challenges of recovery and rebuilding, he noted: “…There is now renewed hope that the lashing from the seas will finally convince everyone of the complete futility of war. Political cartoonists in Sri Lankan newspapers were quick to make this point. One cartoon… showed a government soldier and Tiger rebel swimming to-gether in the currents, struggling to save their lives. (Indeed, there have been reports of them helping each other in the hour of need.) Their common question: what happened to the border that we fought so hard for?”

Alas, that open moment was lost by political bickering, confirming Sir Arthur’s assertion that it is “never possible to forecast what will really happen; it depends on political considerations”. Sir Arthur saw many of his grand visions and dreams come true in his life time, but lasting peace in Sri Lanka was not one of them.

“If There Had Been Government Research Establishments In The Stone Age, We Would Have Had Absolutely Superb Flint Tools,” He Said. “But No One Would Have Invented Steel.”

Rebuilding after tsunami

Sir Arthur was badly shaken by the tsunami’s unprecedented carnage, which also wiped out his own diving company’s installations in Hikkaduwa. In Sri Lanka’s darkest hour, he wept with and for his adopted country – and then collectively counselled the survivors. “The best tribute we can pay to all who perished or suffered in this disaster is to heed its powerful lessons,” he said. “Nature has spoken loud and clear, and we ignore her at our peril.”

In the tsunami’s wake, he renewed his call for better management of our coastal resources, and urged that all remaining coral reefs and mangroves be fully protected. He referred to reports from all over tsunami-affected Asia on how mangroves, coral reefs and sand dunes had acted as natural barriers and absorbed the brunt of the wave impact.

But he was no armchair conservationist, and recognised the practical difficulties involved. “For half a century, I have watched with mounting dismay how the coral reefs were plundered…and been calling for their greater protection. For every person who heeded my call, there were many who did not. Fuelled by a combination of poverty, indifference and official apathy, coral mining has continued to destroy these ‘rainforests of the sea’ – thus eroding our natural defence.”

This fervent plea came from Arthur C Clarke the diver and marine enthusiast who loved to spend time on the beaches of Unawatuna and Hikkaduwa. For decades, he used every conceivable argument to call on the authorities to enforce existing laws and regulations for protecting coral reefs. In a newspaper interview in April 1984, for example, he posed the query: “Ask your readers this question: which is the greater danger – the terrorists who want to divide the country, or the people (coral miners) who are literally destroying it?”

Reacting to intensified coastal erosion in Seenigama and Kahawa on the south coast at the time, Sir Arthur issued a dire prediction: “If the terrorists just sit and wait, the job will be done for them by the sea.”

Not even Sir Arthur could have anticipated the tsunami, but when it happened, he wondered aloud how many thousands of innocent lives could have been saved if right actions had been taken at the right time. His concern was: “As memories of the tsunami slowly begin to fade, it can once again be tempting to resort to these and other gross violations of nature and law.”

Sir Arthur was not a placard-carrying, greener-than-green activist who wanted nature conserved at any cost. Instead, he wanted to see viable job opportunities created for millions of people who would otherwise be forced to return to illicit and unsustainable practices.

Balancing acts

The desire to balance technology, environment and people characterised Sir Arthur’s public advocacy on many fronts (which earned him the Charles Lindbergh award in 1987). This was also the approach he advocated for meeting Sri Lanka’s growing energy needs. Soon after the first OPEC oil shocks in the early 1970s, he wrote that the age of cheap fuel was over, and the age of cheap, unlimited energy was 50 years in the future. In that long interim, he wanted Sri Lanka to achieve a judicious and balanced mix of conventional and renewable sources of energy.

In the early 1990s, as the Science Editor of The Island newspaper, I ran a series of articles that ex-plored energy options for Sri Lanka beyond the finite and imported petroleum. Writing the opening contribution, Sir Arthur said: “Our goal should be to achieve clean, safe and cheap sources of energy that are available to all those who need it, wherever they need it. Options such as solar, wind and biomass have all been proven, while other methods, such as Ocean Thermal Energy Conversion (OTEC), are less widely known and being tested.”

He was fascinated by OTEC, a method for generating electricity using the temperature difference that exists between deep and shallow sea waters. He found out that the Trincomalee Harbour, one of his favourite locations, had ideal conditions for trying out OTEC. His dream – of countering the might of OPEC with our own OTEC – awaits better times.

In contrast, his advocacy for plugging directly into the sun has spawned and sustained the local solar photovoltaic industry for a quarter of a century. In that time, over 75,000 households, mostly in rural areas, have been electrified without burdening the national grid. Besides helping modernise the proverbial ‘village in the jungle’, Sir Arthur saw solar power as the answer to the notorious kerosene bottle lamp responsible for hundreds of accidental fires and burn victims every year.

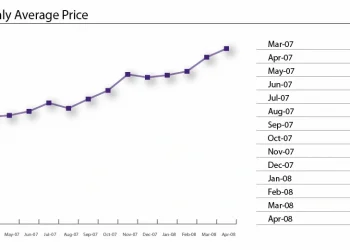

On matters of energy, Sir Arthur liked to quote his friend, the American inventor Buckminster Fuller (of geodesic dome fame): “There is no shortage of energy on this planet, but there is a serious shortage of intelligence!” As we grapple for solutions to our energy crunch and relief from the crushing oil prices, we would do well to go back to Sir Arthur’s published views over the years.

For example, we might find some relief by practising a slogan that he first coined in the 1960s: ‘Don’t commute – communicate!’

The rolling out of telecom networks, especially the spread of mobile phones, allows us to cut down a good deal of unnecessary travel. As more information becomes available on the web or mobile devices in real time, it presents new ways of doing business and enjoying our leisure.

Reducing our needless travel also benefits the global climate. Transport is the biggest contributor of carbon dioxide that traps the Sun’s heat and warms up the planet. Even a few percentage points of travel that we cut down can achieve significant savings in carbon dioxide emissions. Again, Sir Arthur foresaw how improved telecommunications can enhance our lives and also benefit the environment.

“A Guest Must Be Careful About What He Says Of The Host: Contrary To Popular Perception, I Am Not A Sri Lankan Citizen – Only A Resident Guest.”

Age of transparency?

Of course, Sir Arthur’s vision for a digitally empowered Sri Lanka went beyond the utility functions of phone access, internet connectivity, online content and electronic commerce. He was interested in how information societies could improve systems of governance and democracy, continuing a quest that started in ancient Greece.

He shared Winston Churchill’s view – “Democracy is the worst form of government, excepting all the others” – but believed that democratic processes needed some updating to take advantage of new technological possibilities. For example, public-spirited citizens could take advantage of information and communications technologies (ICTs) to hold governments more accountable. Just as satellite television had forced open the flow of news across political borders, the Internet could usher in a new era of transparency, he said.

Around the world, people typically respond to bad governance by rejecting governments at elections, or by occasionally overthrowing corrupt or despotic regimes through mass agitation now known as ‘people power’. To Sir Arthur’s mathematically precise mind, all this was necessary but not sufficient. “The solution must lie in not just participating in elections or revolutions, but in constantly engaging governments and keeping the pressure on them to govern well,” he wrote in 2005.

This new face of people power involves concerned citizens gathering information, analysing it sys-tematically and engaging elected representatives and public officials on an on-going basis. Crucial to this process is accessing information – about budgets, expenditures, excesses, corruption, perform-ance, etc. Sir Arthur held that as ICTs proliferated, such information was becoming more readily available. And if local sources were blocked, resourceful citizens would find other, smart ways to get at it.

He saw this already happening in places as far apart as Brazil and India. “The new breed of citizen voice is thus about using information in a way that leads to positive change,” he said. “In the emerging knowledge-based society, citizens are increasingly using knowledge as a pivotal tool to improve governance, use of common property resources, and management of public funds collected through taxation or borrowed from international finance institutions.”

All this might sound a bit far-fetched in today’s Sri Lanka, where public and private entities still block the free flow of information and there is no legally guaranteed right to information. But let’s not forget how Arthur Clarke’s dreams have a habit of coming true, often faster than his own vivid imagination envisaged.

In the short term, meanwhile, we see the unfolding of Sir Arthur’s vision of mobilising ICTs in education, healthcare and other areas of development. Here again, he saw the hardest task was in making the right choices, policies and investments.

“There is a danger that technological tools can distort priorities and mesmerise decision-makers into believing that gadgets can fix all problems,” he said a foreword to the UNDP’s Asian Human Devel-opment Report in 2004. “A computer in every classroom is a noble goal – provided there is a physical classroom in the first place. A multimedia computer with Internet connectivity is of little use in a school with leaking roofs – or no roof at all. The top priorities in such cases are to have the basic infrastructure and adequate teachers – that highly under-rated, and all too often underpaid, multimedia resource.”

He urged everyone to take a few steps back from the ‘digital hype’ and first try to bridge the ‘Analog Divide’ that has for so long affected the less endowed communities in developing countries. He be-lieved that ICTs could be part of the solution, but not the only solution.

He just loved a cartoon I sourced from an Indian magazine some years ago. It showed a young man armed with every portable communications device telling a poor, old man: “No I have no idea where your next meal is going to come from.”

When Sir Arthur passed away on March 19, the global geekdom was united in its salute — thanking him for having invented the communications satellite, inspired the World Wide Web, and created the supercomputer HAL, a holy grail in artificial intelligence.

Eulogies over, now they can get back to a little challenge he left behind: “The information age has been driven and dominated by technopreneurs – a small army of ‘geeks’ who have reshaped our world faster than any political leader has ever done. And that was the easy part. We now have to apply these technologies for saving lives, improving livelihoods and lifting millions of people out of squalor, misery and suffering. In short, the time has come to move our focus from the geeks to the meek.”

Lost causes

Like any public intellectual, Sir Arthur won some battles and lost others. One area where he made little headway was in countering astrology, a belief system that claims stars and planets control the destinies of men and women – and even whole nations.

Half a century of exposure to the rational Arthur C Clarke has not shaken a majority of Sri Lankans off their obsession with astrology. A life-long star gazer, he repeatedly asked astrologers to explain their basis. Although this challenge was craftily avoided, astrology continues to exercise much influence over the island’s politics, public policy, business and everyday life. When the government technical institute named after Sir Arthur Clarke itself uses astrologically chosen ‘auspicious times’ for commissioning new buildings, the habit is clearly entrenched.

Sir Arthur tried probing some occult and paranormal practices in his TV series Arthur C Clarke’s World of Strange Powers (1985). Even when he didn’t always find full explanations, he showed the value of keeping an open mind and asking the right questions. And instead of ignoring or dismissing popular obsessions, he tried engaging their proponents in rational discussions.

Despite this broad-mindedness, Sir Arthur couldn’t understand how so many highly educated Sri Lankans practised astrology with a faith bordering on the religious (another topic where he had strong views). In later years, he would only say, jokingly: “I don’t believe in astrology; but then, I’m a Sagittarius and we’re very sceptical.”

And in April 2006, when astrologers, nationalists and Buddhist monks pressurised the government to revert Sri Lanka’s standard time to GMT+5:30 from GMT+6, Sir Arthur’s voice of reason was completely ignored. Propagandists of the government-run media asked what business it was for ‘a science fiction writer’ to question public policy.

Perhaps it’s such ridicule that scares away most scientists and other professionals from speaking out on matters of public importance. I could count on the fingers of one hand the number of professionals who joined the standard time debate. When I wrote a commentary on that sad episode for the international website SciDev.Net, my editors introduced it with these words: “Sri Lankan science writer Nalaka Gunawardene is desperately seeking a cheap cloning kit to mass-produce public intellectuals in his country.”

Sir Arthur, long interested in human cloning, was amused to read this, but gave me some friendly advice: “Be careful with what you wish for – it can come true!”

Whatever battles he won or lost, Sir Arthur never gave up the good struggle, and remained an out-spoken public intellectual to the very end. In doing so, he lived a vision that he had outlined over 40 years earlier. Accepting the UNESCO Kalinga Prize for the popularisation of science in New Delhi in 1962, he said: “Two of the greatest evils that afflict Asia, and keep millions in a state of physical, mental and spiritual poverty are fanaticism and superstition. Science, in its cultural as well as its technological sense, is the great enemy of both; it can provide the only weapons that will overcome them and lead whole nations to a better life.”

“We Now Have To Apply These Technologies For Saving Lives, Improving Livelihoods And Lifting Millions Of People Out Of Squalor, Misery And Suffering.”

Walking the talk

It was not just lofty cerebral causes that he championed. From garbage dumps in Colombo and the plight of stray dogs to road safety and media freedom, he was deeply interested in a wide array of social and humanitarian issues. The numerous letters to the editor he wrote in local newspapers were always precise, well argued and often humourous. At other times, he encouraged activists or academics to take up an issue giving freely of his time and ideas.

Confined by Post Polio to a wheelchair in the last decade of his life, Sir Arthur turned his personal plight into a campaign for “user-friendly, barrier-free physical environments” in public buildings for the mobility challenged.

“I didn’t know that we have as many as two million persons with disabilities in Sri Lanka, many of them confined to wheelchairs sometimes at a very young age,” he once wrote in a local newspaper. “I have been waging a battle on my own, urging the proprietors, managers or custodians of public places to introduce relatively simple arrangements like wheelchair ramps.”

The supreme irony, he pointed out, was that some government and private sector institutions serving the needs of disabled soldiers were also totally inaccessible to those using wheelchairs! From his own wheelchair, Sir Arthur ‘walked the talk’: he declined to attend any public event held at a venue that didn’t support wheelchair access.

He also challenged architects and town planners – many of them trained at the University of Moratuwa where he was Chancellor for 23 years (1979 – 2002) – to ensure that all new buildings and city structures were designed as wheelchair friendly. He once suggested: “Perhaps we should ask all new architects to spend an entire day on a wheelchair, going about with their daily business. That will surely make them realise what a struggle wheelchair users face everyday!”

Tongue in cheek

Despite his impeccable credentials and multiple accolades from around the world, Sir Arthur was no crusty academic. Indeed, he was critical of ‘ivory tower’ universities and research institutes and poked fun at intellectuals with their heads in the cloud. He cheered – and sometimes personally helped – lone inventors and maverick scientists swimming against the current of conventional wisdom. He was fond of quoting Mark Twain: “The man with a new idea is a crank – until the idea succeeds”.

He welcomed governments and industry funding research, but didn’t want bean-counters in charge of discovery and invention. For many years, he gleefully peddled the well known joke among scientists about the discovery of the heaviest elements known to science: Administratium and Bureaucratium. “If there had been government research establishments in the Stone Age, we would have had absolutely superb flint tools,” he said. “But no one would have invented steel.”

Sir Arthur was a great deal more than his public persona. Those who knew him remember a cheerful man who loved to share good jokes; had a rich collection of anecdotes, limericks and brain-teasers; and had a child-like fascination for the latest gadgets and computer software. He also had the capacity to laugh at himself – and at various Sri Lankan idiosyncrasies (see box: Sir Arthur’s close encounter with cricket).

His optimism and enthusiasm were infectious, and these qualities never left him despite his own failing health or while living through turbulent times in Sri Lanka. He never missed an opportunity to promote Sri Lanka’s image overseas: for millions of readers and television viewers worldwide, Sri Lanka was simply the island where Arthur C Clarke lived. When asked by ill-informed foreign journalists whether he missed home (England, his land of birth), he quipped: ‘This alone is my home now’.

There’s some incongruity that we left Sir Arthur six feet underground at Colombo’s general cemetery on a sombre March afternoon. The late Bernard Soysa, a leading leftist politician and one time Minister of Science and Technology (and a friend of Sir Arthur), once called it ‘the only place in Colombo where there is no discussion and debate’.

Arthur C Clarke’s Close Encounter with Cricket

Sometimes Sir Arthur spoke with his tongue firmly in his cheek, and that landed him in trouble. In early 1996, he told a Reuters correspondent that he shared the (minority) view that cricket was the slowest form of animal life: test cricket in particular can drag on for days and yet end up without a result.The reporter apparently mis-heard Sir Arthur, and quoted him as saying cricket was the ‘lowest form of animal life’. For cricket-worshipping Sri Lankans, this was blasphemy – and Sir Arthur soon found out how the English game of cricket had evolved to become South Asia’s dominant religion. Clarifying matters in a media statement, Sir Arthur said: “During a phone interview, I protested about the continuous coverage of cricket matches – to the virtual exclusion of world news and other important features – on most of our TV channels. As one who enjoys this elegant game for a maximum of ten minutes, I repeated the well-known and perfectly good-natured joke that cricket is the ‘slowest form of animal life’. ‘Slowest’ has been converted to ‘lowest’, thus completely ruining the pun.” In fact, by inventing communications satellites, he had inadvertently contributed to the mass hysteria inspired by the game of ‘flannelled fools’. The day after Sir Arthur’s explanation was released to the media, Sri Lanka won the cricket World Cup — in the euphoric afterglow, die-hard fans and editorialists continued to be irked by what they considered an ill-timed snub by the country’s most famous foreign resident (hailing from the land of cricket, no less). If Sir Arthur was taken aback by all this, he took it in his stride. “When an important cricket match is being broadcast live, I have to look hard to find any signs of life on the streets of Colombo,” he wrote in 2003. And he once privately joked how easy it would be to stage a coup in Sri Lanka on the night of a cricket final..

Sir Arthur, a passionate public intellectual to the very end, has surely earned his peace and quiet. But we who want his legacy to continue must be relentless: never allowing a moment’s peace to the as-sorted bureaucracies, hierarchies and oligarchies that constantly undermine and invade the public sphere. And keep looking for that cheap cloning kit.

Nalaka Gunawardene worked closely with Sir Arthur Clarke for 21 years (1987 – 2008) while pursuing his own professional interests as a science writer and broadcaster. He was a researcher for several Clarke books, and coordinated his media, scientific and academic relations. Nalaka blogs on media and society at: http://movingimages.wordpress.com