Farah Mihilar

Plantations have come under a spotlight ever since their privatization. But the biggest difference the privatization process has brought to the plantations is the turnaround in their revenues.

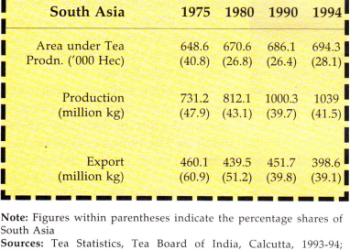

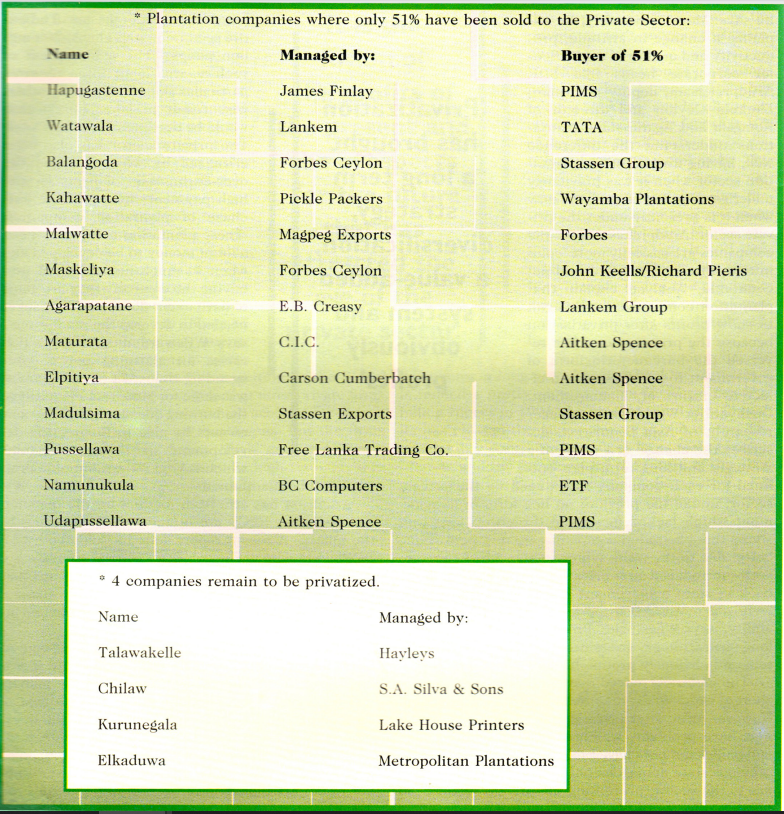

The Sri Lankan government sold 51% stake of the share holdings of 5 plantation companies this month. Maturata Plantations, Malwatta Plantations, Namunukula plantations, Kahawatta plantations and Alpitiya plantations were purchased by the Employees’ Trust Fund, Wayamba Plantations, John Keells Holdings, Forbes Ceylon and Aitken Spence respectively, earning a total of Rs 10.2 billion. This year’s earnings only tipped last year’s figure by Rs 2.3 million. In 1996 State funds gained Rs 1.57 billion from the sale of 6 plantation companies.

Plantations have taken center stage in the Sri Lankan economy ever since the companies were privatized last year. The eyes of the corporate world seem to have been focused on the plantations since then, with the sector offering more to investors than the other industries. Analysts vary in their views on the success of plantation companies but almost all stand firm on the fact that plantation companies have shown a marked improvement since their privatization.

‘Privatization’, the word itself is often spun in controversy and the privatization of plantations has its fair share of controversy as well. However ‘privatization’ and ‘plantations’ have a far greater link than any other industry. This is mainly due to the success plantation companies have shown since privatization.

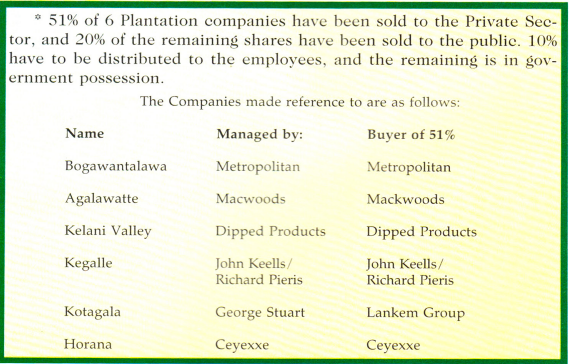

The plantation sector has always been a dominant income earner for Sri Lanka. In early 1991, however, a government decision to handover 23 regional plantation companies (RPC’s) to the private sector saw the turning point in the industry. This led to the privatization of RPC’s in 1995 with 6 companies going public subsequently. The following diagram shows the current standings and ownership of 23 RPC’s in Sri Lanka.

Privatization of RPC’s brought with it not only new management, but most importantly, the companies started showing higher profits. From 1994 to 1995, companies that were privatized showed almost 100% profits. Of the companies to release their annual reports for the year 1996, Kegalle plantations has shown a profit of Rs 92,859,981 compared to the previous year’s Rs 66,164,425, whilst Horana Plantations. showed a Net Profit of Rs 52,733,000 for ’96, as against Rs 37,630,000 in 1995.

The burning question in everybody’s mind at present is ‘What difference has the privatization process brought to the plantation sector? Most analysts refuse to quantify the difference but all were fast to explain the facts. Rohan Fernando of Aitken Spence Plantations explained in two words the biggest dif ference privatization has brought to the plantation sector, plantation companies have become more. commercially responsive, he explains. Lucile Wijewardene, MD, Hayleys Plantations agrees. “There has been a huge, massive change after privatization,”

he says. More elaborately, he explains ‘a change in attitude, productivity and quality of work.” Senior corporate heads like SDR Arudprakasam, deputy chairman, Lankem Ceylon and director of Kotagala and Agarapatana plantations understand the difference well, having worked in the plantation sector when it was previously under government control and now when it is presently under the private sector. Arudprakasam says the companies are basically more ‘committed, directed, focused and accountable. Analysts explain that plantation companies have begun to show profits after privatization because the private sector has reversed the bureaucratie form of government to an efficient and effective form of management. Dushyantha Wijesinghe, manager research, of Asia Securities, describes the change as a result of a strategic and long term plan outlined for each company introduced by the private sector, unlike the previous ad hoc form of management which lacked focus and direction. Research shows that plantation companies are now performing better due to the traits synonymous with the private sector introduced after privatization. “The main drawback in state management was that the employees were not motivated to perform to the best of their ability,” says Wijesinghe. Privatization has brought a long term strategy, diversification, a value-added system and obviously profits, he says.

The picture is indeed rosy. Analysts are in no way short of words to express the benefits of privatization. However, even after privatization plantation companies have problems which cannot be ignored. The companies not only have problems inherited from the previous state management but also problems inherent to the sector, preventing the private sector from blinding themselves to the current upward trend in profits.

Plantation companies have a major risk factor associated with them. Tea, rubber and coconuts, are volatile products, the yield of these crops depend on unpredictable factors such as the weather. Prices of tea, and rubber are also highly dependent on World prices and the performance of big players in the World market. At present, all commodities appear to fetch high prices. However, the trend is in no way predictable. Plantations are also greatly dependent on the labor force. Not many people understand that this is the only industry which employs labor to this extent,’ says Arudprakasam. The entire sector employs almost 300 million people. The management of such a large labor force requires particular skills which could other- wise result in labor unrest that would be detrimental to the sector. The private sector has also been criticized by what is called the over enthusiasm of firms for the high payments made for the purchase of plantation companies. “These plantation companies need a lot of money to be developed and when so much money is put into buying the company they are going to have to cut down on the finances needed to develop the plantations,” says Wijewardene. A fact which raises an alarming point. After spending almost Rs 61 per share ast was done for Madurata Plantations, the burning question is will the new owners be able to finance the development of these companies which is vital if the admirable profits are to be maintained.

Attention has also been focused on the question as to whether RPC’s are utilizing their resources to the fullest. A recent report done in Colombo by AP DOW Jones shows the extent to which resources are neglected at the plantations. The report explains that ‘Sri Lanka has an uncultivated land area in excess of 15%, laying bare pristine, arable land for further investment opportunities.”

Despite the pitfalls plantation companies seem to be in demand. In the recent past the private sector has shown keen interest in them, firstly by managing RPC’s and later by taking possession of most of the companies. Most people appear to ask the question, ‘why is the private sector showing so much interest in the plantation sector?” “Plantation companies are profitable,’ explains Arudprakasam. Tea and Rubber prices are high so profits are flowing in, he says. Analysts agree. ‘Kenya has had problems in the World tea market which has put Sri Lanka in a comfortable position,’ says Panduka Ambanpola head of research, Jardine Fleming. Lucile Wijewardane has a different view, I don’t think it has much to do with prices, Man has always had this desire for land. It is the greed for land,’ he says. An interesting factor when understanding the desire of the private sector with regard to plantation companies. “They see a huge potential with land of this nature,’ says Rohan Fernando. It appears to be the attractive combination of high tea and rubber prices and the potential use of land. It is the fusion of the profits of the present and the prospects for the future that has attracted the eye of the private sector.

Tea plantation experts also explain that some companies like John Keells Holdings have been in the trade and therefore expanding It is the fusion of the profits of the company from being a mere tea the present and the prospects for the future that has attracted the broking firm to an owner of tea plantations can only be profitable. Companies like JKH are cash-rich, they are big conglomerates, when they see a good investment opportunity they take it,’ says Ambanpola. It is questionable though if these companies are aware of the risk involved in the plantation sector. The private sector must realize they will always be victims of volatile prices, unpredictable weather patterns, possible labor disputes and intense competition in the World market. Arudprakasam explains that most private firms ensure that plantation companies account for only a certain percentage of their businesses. But the firms have their usual confidence. ‘Risk’ does not pose a problem to them, ‘If there is to be high returns there will always be risk,’ says Fernando with a simplicity that is probably the secret of the private sector’s success with plantations.

The privatization of plantations have another aspect which has taken a back seat amidst all the excitement. That is the fact that 10% of the share holdings has to be distributed amongst employees. This has not been done yet. Arudprakasam explains that distributing shares amongst so many employees is not easy but he confidently assures that it will definitely be done. Most companies have already begun the process of listing the employees and calculating the quantities to be distributed,’ he says.

The plantation sector has indeed come a long way. Looking back at statistics it is indeed a pretty picture. From losses of nearly 7 billion rupees in 1991, the present trend of high profits has pleased the major players in the sector. The profitability continues to attract large scale investor interest and the prospects for the future of the plantation sector in Sri Lanka can only be positive.