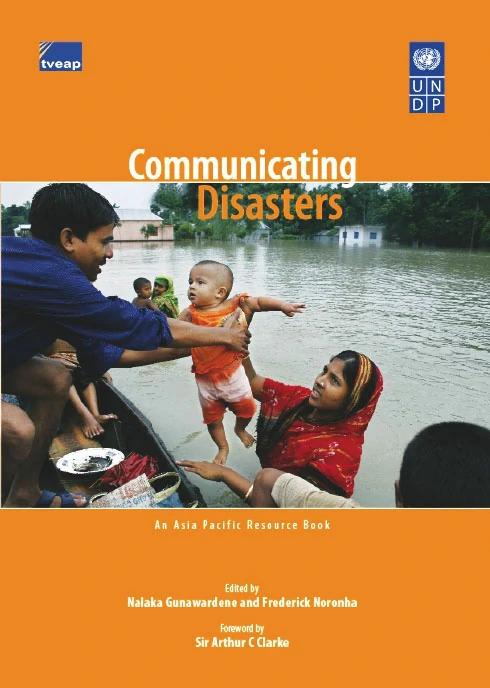

A new Asian book takes a critical look at the communication lessons of the Indian Ocean tsunami of December 2004, and explores the role of good communications before, during and after disasters.

Titled ‘Communicating Disasters: An Asia Pacific Resource Book’, the multi-authored book discusses how information, education and communication can help create disaster resilient communities across the Asia Pacific region, home to half of humanity. With its release coinciding with the third anniversary of the tsunami, the book carries an entire section reflecting on the communication lessons of that mega-disaster.

Drawing on the tsunami, Kashmir earthquake and other recent disasters, the book concludes: adequate planning by media and disaster managers can help avoid communications disasters.

With focus on the appropriate use of media-based communications, the publication covers rapid on-set disasters such as tsunami, earthquakes, cyclones and landslides as well as those that unfold slowly, such as drought.

The book, co-published by the non-profit media foundation TVE Asia Pacific and the UNDP Regional Centre in Bangkok, brings together 21 authors – most of them from Asia – who share their experiences and insights on effective communication related to various disasters.

It was released during the Third Global Knowledge Conference (GK3) held in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, from December 11 – 13, 2007. The role of information and communication technologies (ICTs) in disaster prevention and early warning was discussed during the event, attended by 1,700 people.

Communicating Disasters was edited by two leading Asian journalists – Sri Lankan Nalaka Gunawardene and Indian Frederick Noronha – and carries a foreword by Sir Arthur C Clarke, inventor of the communications satellite.

“Communicating disasters — before, during and after they happen — is fraught with many challenges,” Sir Arthur C Clarke says in his foreword. “Today’s ICT tools enable us to be smart and strategic in gathering and disseminating information. But there is no silver bullet that can fix everything. We must never forget how even high tech (and high cost) solutions can fail at critical moments. We can, however, contain these risks by addressing the cultural, sociological and human dimensions.”

The book’s contributors come from backgrounds in print and broadcast media, photojournalism, the UN system, civil society, academia and the humanitarian sector. They draw on their rich and varied experience in either preparing disaster resilient communities or responding to humanitarian emergencies triggered by specific disasters. Five chapters are written by leading Asian journalists who covered the aftermath of the Indian Ocean tsunami.

“This book comes out at a time when both the media industry and the global humanitarian sector are undergoing rapid change,” says co-editor Nalaka Gunawardene, who is also Director of TVE Asia Pacific. “Our contributors are among the ‘change agents’ leading or consolidating these changes, and thus able to offer insights from the cutting edge in their respective spheres.”

Whenever a hazard turns into a disaster of any kind, journalists and humanitarian workers are among the first to arrive on the scene. But their needs and agendas are different: journalists have to access and verify real time information, and get their story out ahead of the competition, while the priority for humanitarian workers and disaster managers is to provide relief to affected people.

“In the information age, disaster managers have to balance their own humanitarian priorities with the need to manage information flows and maintain good relations with the media,” the book points out. Several chapters explore the nexus between journalists and humanitarian workers, identifying the common ground for them to cooperate better.

While ICTs – ranging from radio and television to computers and mobile phones – make it possible to reach more people faster, the book emphasises that technology is insufficient to achieve this potential. “It requires a mix of sociological, cultural and institutional responses by governments, corporate sector and civil society. This also calls for building or reinforcing ‘bridges’ between media practitioners and disaster managers who have traditionally been on two sides of a divide.”

Asia’s recent experiences have shown how governments, civil society and aid agencies mismanage information and communication, aggravating the agony of affected people and wasting limited resources. As the book’s introduction says, “There is growing recognition on the need for a culture of communication that values proper information management and inclusive information sharing.”

The book also quotes from the World Disaster Report 2005, published by the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC), which made a strong case for a greater role for information and communication in disaster situations: “Information is a vital form of aid in itself – but this is not sufficiently recognised among humanitarian organisations. Disaster-affected people need information as much as water, food, medicine or shelter. Information can save lives, livelihoods and resources.”

“The discussion on the role of information and communication in disaster situations continues,” the co-editors Gunawardene and Noronha say in their introduction to the book. “Media-based communication is vitally necessary, but not sufficient, in meeting the multiple information needs of disaster risk reduction and disaster management. Other forms of participatory, non-media communications are needed to create communities that are better prepared and more disaster resilient.”

They add: “This book does not claim to provide all the answers, but we hope it has at least raised many pertinent questions. Instead of trying to be comprehensive or definitive, our contributors are being provocative and imaginative.”

The book is the culmination of a year-long process that began with an Asian brainstorming meeting on communicating disasters that TVEAP and UNDP convened in mid December 2006 in Bangkok, Thailand. That meeting, attended by three dozen participants drawn from the media and disaster management sectors, identified the need for a handbook that could strengthen cooperation of these two communities before, during and after disasters.

The 160-page book comprises 19 chapters and seven informative appendices. It is richly illustrated using images drawn from Drik Picture Library, PhotoShare, TVEAP image archive and the work of individual photographers across Asia.

The book is aimed at journalists and disaster managers who often have to communicate under pressure during the aftermath of disasters. It is also a useful guide to civil society groups who are keen on using information and communication to create safer societies and communities.