Dr JB Kelegama

After twelve years of cooperation, SAARC agreed in April 1993 to establish a SAARC Preferential Trading Arrangement (SAPTA), as an umbrella framework for step-by-step liberalisation of intraregional trade through periodic rounds of trade negotiations for exchange of trade concessions on tariff, para-tariff and non-tariff measures. SAPTA, like other sub regional groupings, gives special and favorable treatment to the least-developed countries (LDCs) in the grouping. It also contains provisions for safeguard action and balance of payments measures to protect the interests of member states during crises.

The first phase of trade negotiations on the basis of bilateral offer and request lists, product by product, was completed and the first consolidated tariff schedule of tariff concessions on 226 products was finalized and ratified by all member states and came into effect on 7 December, 1995. This is regarded as the first step towards greater liberalization of sub- regional trade through gradual removal of para-tariff and non-tariff barriers, widening and deepening of tariff cuts and expanding the list of concessionary products in order to achieve a South Asian Free Trade Area (SAFTA) in the future.

Unsatisfactory Start

The first round of trade negotiations and the 226 tariff preferences it resulted in seem to hold little promise of a regional trade expansion for the following reasons:

- The value of preferential imports (those items receiving tariff preferences) is too small to make an impact on the intratrade of the region. In 1993, for example, the value of preferential imports of member states was about 6% of that of total intraregional imports among them, i.e. US$73+ US$1163 x 100. In the case of India, the largest trader in the grouping, her preferential imports form about 10% of its total imports from the region. Further, India’s world imports of negotiated products constituted less than 2% of her global imports of all products. As for Sri Lanka, preferential imports amount to about 7% of its imports from the region and her world imports of negotiated products were a little over 2% of her global imports;

- Of the 226 tariff preferences, 100 are targeted in favor of the least developed countries. Thus, the preferences exchanged by other countries with one another are only 126;

- The preferential margin in tariffs is relatively small, in most cases only 10% of the MFN tariff rates. Of the three countries with the highest tariffs in the region, only India offered tariff cuts of 50 to 100% while Bangladesh and Pakistan have offered only minor cuts of 10 to 15%. The MFN tariff rates of Bhutan, Maldives, Nepal and Sri Lanka are relatively low yet they have made tariff cuts of 10 to 20%;

- Some of the tariff preferences are of no practical value as they are a mere duplication of preferences granted under other arrangements earlier. For instance, 25 of the 149 products granted preferences by Bangladesh, India and Sri Lanka do not stand to gain any benefit as they have received equal or higher preferences under other arrangements. Of the 18 products offered tariff preferences by India to Sri Lanka, 17 have the same preferences as those extended by her under the Bangkok Agreement; thus Sri Lanka will not derive any benefit from these concessions;

- Tariff preferences have been granted to a large number of products which are not being traded in the region at present. For example, of the 106 products offered preferences by India, only 22 are being imported; thus preferences on 84 items are of no practical value. Similarly, Pakistan imported only 13 of the 35 products it had offered preferences. This reminds us of the tariff preference extended to snowploughs in ASEAN! On the other hand, tariff preference have not been exchanged on many items which are being traded on a large scale and they continue to bear the high tariff rates 60-70% in some countries;

- Trade preference exchanged were confined to tariffs. Thus, even those products for which tariff preferences have been granted may be subject to non- tariff restrictions such as import licensing, prohibitions, paratariffs, canalization through state trade corporations and technical specifications. Meaningful trade liberalization can be achieved only if tariff preferences are combined with relaxation of non-tariff restrictions, but SAPTA has not yet advanced to this stage.

Limited Complementarity

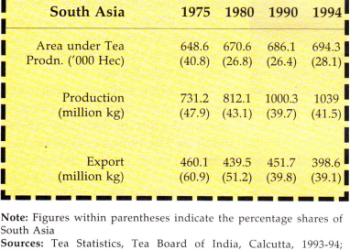

The main constraint to the expansion of regional trade in SAARC is the limited complementarities in trade among the countries of the region. What this means in practical terms is that what is demanded in the region is not produced at all or in adequate quantity in the region and what is produced in the region is not demanded at all or in adequate quantity by the region. This is mainly the result of almost all the countries of the region being in a similar stage of development and producing similar export products both in agriculture and industry, partly on account of their colonial history of producing the food and raw materials needed by the metropolitan powers and partly owing to the establishment of the same type of industries on their road to industrial development. Thus their export production is mainly geared to meet the demand of developed industrial countries whether they be agricultural products like tea, jute, cotton, rubber, spices, leather or industrial products such as cotton fabric, garments, diamonds, jewelry and rubber and leather products. Their imports similarly are mainly from the developed countries as manufactured goods they require are produced mainly by them and furthermore they are used to them. Their trade pattern thus is not one conducive to the rapid expansion of mutual trade.

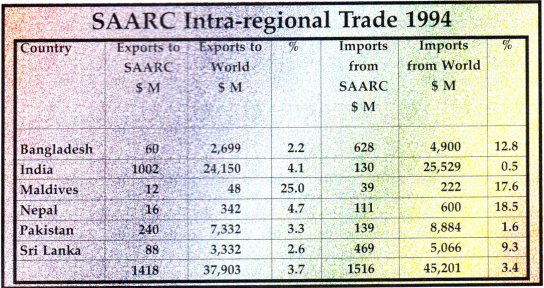

Trade among the member states of SAARC or intraregional trade is as low as 3 to 4% of their world trade. In fact, it has declined since the establishment of SAARC-from 4.5% of world trade in 1985 to 3.5% in 1994 – indicating that trade complementarities have shrunk in the last decade. In the case of exports, the share of exports destined to the region is below 5% of their world exports in all countries except Maldives. This share in 1994 was 2.2% in Bangladesh, 2.6% in Sri Lanka, 3.3% in Pakistan, 4.1% in India, 4.7% in Nepal and 25.0% in Maldives (virtually all exports of Maldives are to Sri Lanka). Taking SAARC as a whole, its intraregional exports med 3.7% of its world exports in 1994. The picture is different. Se intraregional imports. The share of imports from the region was high for Nepal (18.5%), Maldives (17.6% ), Bangladesh (12.8%) and Sri Lanka (9.3%), while it was low for Pakistan (1.6%) and India (0.5%). For SAARC as a whole intraregional imports formed only 3.4% of its total imports from the world. Net importers in SAARC are Bangladesh, Bhutan, Maldives, Nepal, and Sri Lanka, while the net ex- porters are India and Pakistan.

A major reason for the low volume of intraregional trade is the relatively small volume of imports by India and to a lesser extent Pakistan. India is the region’s largest exporter to other SAARC countries: her exports of US$1002 million in 1994 accounted for 71% of SAARC’s intraregional exports; as shown earlier, they formed 4.1% of India’s total exports to the world. India’s imports from the region, however, are relatively small and are not commensurate with her exports. In 1994, for instance, her intraregional imports amounted to a mere US$130 million which was even lower than the intraregional imports of Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and Pakistan and they formed only about 9% of the total intraregional imports. They were about 13% of the value of her intraregional exports and formed a mere 0.5% of her total imports from the world. Pakistan’s imports from the region too are relatively small; they formed 58% of her exports to the region in value; they were 1.6% of her world imports while her exports to the region were 3.3% of her world exports.

Indian Market

The fact that India is not purchasing enough goods from other SAARC countries is partly due to denial of access to exports of these countries by tariff and non-tariff restrictions in the Indian market but mainly on account of the fact that these countries are not producing the type of goods demanded in India. India has a broad and diversified industrial base in addition to its traditional agricultural base and its import needs are being increasingly met by countries outside the region. The trade complementarities

based on agricultural products and light manufactures between India and the others seem to have reached their limits with increasing self-sufficiency in food and high industrial development. The logical way out of this impasse is for other SAARC countries to begin producing those goods demanded by the Indian market but this involves a gigantic and costly exercise in industrial restructuring and product diversification of these countries. Besides, under the free-market and free-trade policies being pursued under IMF instructions by all these countries, there is no guarantee that even if these goods are produced at a later stage, they will find a market in India as they may not be competitive with products from outside sources.

The direction in which the SAARC countries are moving under free-market policies is also likely to reduce the existing trade complementarities of the region further and thereby reduce the intraregional trade in the future. All the SAARC countries are pur- suing export-oriented policies and inviting foreign capital mainly from transnational corporations to develop their resources. Private enterprise including transnational corporations are investing in those sec- tors which give them the highest profits and not those which are considered desirable by the national gov- ernments or SAARC. Generally, they are investing in import-substitution industries and other industries like garments, electronics, cut diamonds or fresh fish -the products of which are to be sold outside the region. There is like evidence of new export indus- tries being established in the much publicized export processing zones or elsewhere for the South Asian market. Thus, with the new export industries, SAARC countries are increasing their trade complemen- tarities not with countries in the region but with those outside and thereby strengthening the tendency for trade to grow with outside countries more rapidly.

A breakthrough may be possible by means of joint ventures incorporating buyback arrangements with India, but India may not be enthusiastic about them partly because she has little surplus available for foreign investment and partly because the labor costs in other SAARC countries are not very different from hers. Further, other SAARC countries do not seem to attach sufficient importance to such ventures and to the Indian market as their new exports are doing well in other markets.

Tariff preferences alone not enough

In this situation, it is doubtful whether tariff preferences alone and marginal preferences at that – can contribute to an expansion of intraregional trade Lower tariffs relative to third countries, which result in lower import prices, do not automatically result in exporters increasing their exports to the region as there are other factors which are necessary for trade to take place. Even if the prices are lower, the goods. should be available in adequate quantity and regularly in the exporting country and they should be of comparable quality and standard as those already imported from third countries. These factors in fact, are more important than tariff preference. Only India has a relatively diversified export base which explains her large export surplus in regional trade.

One wonders also whether SAARC should spend so much time and energy on negotiating tariff preferences when all of them are in any case reducing their tariffs under pressure from the IMF. India for instance, has reduced its maximum level of tariff to 110% and tariff on capital goods to 55%. The process of trade liberalization is still going on and if on ac- count of IMF pressure, trade regimes in all SAARC countries become truly liberalized with low tariffs and free imports, then trade preferences become superfluous. For example, a 50% preference on a 60% tariff rate will bring down the preferential tariff rate to 30% whereas a 50% preference on a 12% tariff rate will reduce it to 6%; thus, the effect on price of the latter is much less than the former. Similarly, if imports have few restrictions, the question of preference does not arise in non-tariff barriers.

The assumption that tariff preferences result in mutual trade expansion is not supported by the experience of almost all the preferential tariff arrangements of developing countries. The Bangkok Agreement of 1976 between Bangladesh, India, Republic of Korea, Laos and Sri Lanka is one of the oldest preferential tariff arrangements in Asia but the Intra-trade of its member states actually declined in 1980-1990. What is more significant is that the imports which had been given tariff preferences actually declined in value between 1981 and 1986 almost half of the concessional items having no record of import from member countries. In nearly all preferential trading groupings in Africa, Latin America and the Middle East, mutual trade has stagnated in recent years. Even in ASEAN, mutual trade declined as a share of world trade between 1980 and 1990, although the number of trade items granted tariff preference rose from 71 in 1976 to 20,000 in 1990.

The Bangkok Agreement is moribund. Its intraregional trade is so small and stagnant that it has not warranted the setting up of a secretariat as in other similar organizations, the secretariat functions being performed by the ESCAP Secretariat. Although its original intention was to cover the whole Asian Pacific region its membership has remained at five from the inception with no new additions. Its annual meetings are routine and little worthwhile is discussed, for the members know, although they do not say so in public, that it has no future. Will SAPTA suffer the same fate?