KLAUS BRINKBÄUMER and THOMAS SCHULZ

From Der Spiegel

© 2010 Der Spiegel

Distributed by The New York Times Syndicate

The Apple story, which is Jobs’ story, can be described in six chapters, as told by six contemporary witnesses, each of whom spent time with Apple from its humble beginnings through to its current position as one of the most powerful companies in the world.

I. The Founder

The Apple story begins in a garage in Los Altos, south of San Francisco, Calif. The setting is the Jobs’ family garage in 1976. Jobs and his friend Steve Wozniak are tinkering with a computer prototype. The two youths in T-shirts and cutoff jeans dream of great things: an affordable computer for everyone.

Each has a different role to play in that dream. Wozniak dreams of building the machine; Jobs wants to sell it.

Back then, computers were for rich companies and the CIA, enormous machines that cost $100,000 at least. However, Wozniak has been working on a new computer for 13 years. He knows he has talent and a feel for technology, yet he has no idea how revolutionary his talent will be. He first gets a glimpse on a Sunday evening in June 1975, when he takes two cables and connects one of his computer prototypes to a screen and a keyboard.

“I didn’t realize how significant that was,” says Wozniak. He laughs.

“It was the first time anyone typed a letter on a keyboard and the letter appeared on his computer monitor at the same time,” he wrote in his autobiography.

A Young Woman Storms In Followed By Armed Police. She Shatters Big Brother And Frees The Enslaved Masses. The Woman Is Apple. A Voice Announces: “On Jan. 24, Apple Computer Will Introduce Macintosh. And You’ll See Why 1984 Won’t Be Like ‘1984.”‘

On April 1, 1976, the two friends found the Apple Computer company. Wozniak takes care of the technology while Jobs hires new employees – though not too many. There always has to be more work than employees, he says. Jobs finds an investor and organizes the sale of a product for which no market yet exists.

In June 1977, the Apple II computer is introduced to the market. Price: $1,298, including keyboard, excluding monitor. It’s the first computer for ordinary people, and it becomes a worldwide sensation, with over 2 million in sales. A beginning.

“Everything we made turned into gold, really nothing existed, everything was brought into the world for the very first time,” says Wozniak. But he leaves Apple in 1985. “Steve saw (the personal computer) as the future of a company, I saw it as my entire life,” he says, “I didn’t want to be in the limelight anymore.”

II. The Magician

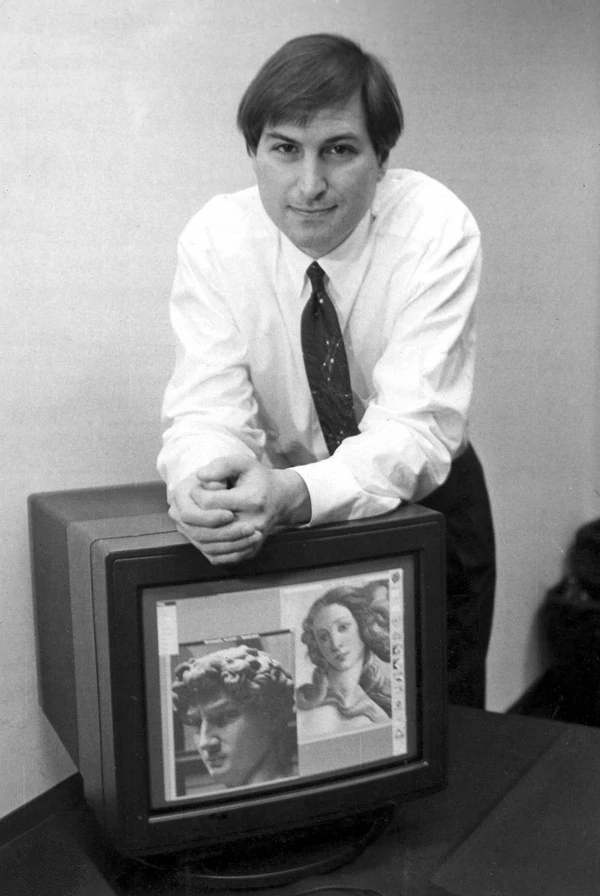

In a world of high-resolution interfaces and sensory touch screens, it’s easy to forget how a PC looked in the early `80s. Green type glowed on a black background; commands were entered by keyboard. A PC was something for technology fans alone.

In 1979, Apple begins work on a new computer. Jobs soon assumes leadership of the development department; he wants something unprecedented. The Macintosh is supposed to reflect how its developers see the world. The Mac proves to be the first mass-produced PC with a graphical interface and windows that can open on top of one another. And it has a mouse.

“It was clear to us that every computer in the world would be like that in the future,” Jobs said years later.

Andy Hertzfeld, a key member of the Mac’s development team, says: “Apple doesn’t want to make a product that is the most lucrative financially or the most impressive technically. It should be the greatest thing in and of itself, simply perfection.”

The Mac is introduced on Jan. 22, 1984 in a 30-second commercial during the Super Bowl; the ad is filmed by Hollywood director Ridley Scott. You see endless rows of workers, a joyless army and a being like “Big Brother” from George Orwell’s apocalyptic novel “1984”; the army is IBM, at that time still an Apple rival. A young woman storms in followed by armed police. She shatters Big Brother and frees the enslaved masses. The woman is Apple. A voice announces: “On Jan. 24, Apple Computer will introduce Macintosh. And you’ll see why 1984 won’t be like ‘1984.”‘

Almost 80 million television viewers are fascinated and bewildered. Advertising experts consider the ad to be the best in the industry’s history.

Apple succeeds in doing what most big companies only try to do: associate products with emotions and embellish them with values until the products themselves turn into values. Apple seduces. Whoever buys a Mac is young, creative and revolutionary, therefore cool. “Think different” later became Apple‘s slogan, and who doesn’t want to think differently?

III. The Artist

The house is like an Apple computer. White, wide and warm. On the outside are olive trees and palms, on the inside white walls and chrome, a grand piano, Chinese tea service, Meissen porcelain.

Hartmut Esslinger can speak both German and English; he has lived in California for decades. Esslinger is also the greatest designer in his world. Esslinger founded Frog Design in 1969, in a garage in Altensteig, which is in Germany’s Black Forest region.

“Design isn’t packaging. Design is a way of thinking, design thinks about the entire product,” Esslinger once said. “Design is not only how something looks and how it feels. Design is how something works,” Jobs said a few days later.

“Sometimes Steve hears something, then he presents it as his theory,” Esslinger says today, laughing. He regards Jobs highly, especially his boldness.

Jobs called on Esslinger because he needed a design for a graphical user interface, but Esslinger believes “that people sometimes don’t know yet what they want.” He also believes that “good design must find the exact balance between provocation and familiarity, or between absurd and boring.” That’s why he suggested something different to Jobs: white computers. “California white,” he called it. “The computer industry has never understood that people develop an emotional attachment to things,” he said. Naturally, Jobs also spoke this sentence, word for word, at a conference days later.

“Be insanely great” – those were Jobs’ orders. As the Frog people built prototypes, the artists and engineers were in constant exchange, and Jobs let them build. Frog received $200,000 per month – a lot of money for something that no one in the conservative Silicon Valley took seriously.

25 years later, designers and advertisers praise no cooperative effort more highly than the collaboration between Esslinger and Jobs. “Understand what people need. Develop things that make life easier and add joy. That’s the Apple secret,” according to Suze Barrett, creative director of the Scholz & Friends ad agency in Hamburg. While other computer companies were committed to the technology, “Apple focused on what is comprehensible and useful for people. So Apple products were a symbol of a new lifestyle, the ‘digital lifestyle’ in which design plays the essential role.”

Apple’s devices look simple and functional. That idea was really stolen, from Braun pocket calculators for one, but Apple products remain what advertisers call “must-have products.”

Apple focused on what is comprehensible and useful for people. So Apple products were a symbol of a new lifestyle, the ‘digital lifestyle’ in which design plays the essential role.

The “i” that adorns essential Apple projects once stood for “Internet” and today stands for “I.” It’s about self-realization, or the illusion of it. “Must something be unusable if it’s art? Can’t art be something that’s usable?” asks Esslinger, who is now a professor in Vienna and writes books containing phrases like “seeing is believing, believing is seeing.”

Apple presented the first Esslinger computer, the Apple IIc, in Jobs’ office in Cupertino, Calif. – 25 models, all white. Jobs didn’t look pleased. “I hope it works,” he said. “I’m not convinced.” On the first day, Apple sold 50,000 units. That was on April 24, 1984. Today, the Apple IIc stands in the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York City.

IV. The Enemy

Jobs was never infallible, though he is worshipped. He wasn’t even always the “best CEO in the world,” as Google chief Eric Schmidt calls him. For a while, he wasn’t even CEO.

In 1980, after Apple’s initial public offering and the beginning of the company’s expansion, its board of directors want to install an experienced manager as head, one who can supervise the difficult Jobs, and show him how a global company can be run: respectably.

Jobs doesn’t put up a fight, but he wants to have a say in the selection, and he only wants one man: John Sculley, head of Pepsi-Cola, a marketing expert clueless about the computer business. He courts Sculley for 18 months, then finally Jobs says: “Do you want to spend the rest of your life selling sugared water or do you want a chance to change the world?”

Sculley accepts. And Jobs likes Sculley: They hike together in the hills of Northern California. The press calls them the “Dynamic Duo.” But after two years Sculley and Jobs have a falling-out. Things had devolved into a showdown: Who has the power, the founder or the manager? The one with vision or the respectable one? The board decides in favor of Sculley. In the fall of 1985, Jobs leaves Apple – his baby, his life.

Sculley remains. For eight more years.

“I believe it was a huge mistake to take me on (the job) as CEO,” says Sculley in early 2010. He is sitting at a solid conference table in New York City, with a window overlooking Central Park behind him. “The management board should have made Steve head.”

Why would he say something like that? What CEO downplays his own achievements? Shouldn’t he talk about how the company grew under his leadership from $600 million in turnover to $8 billion? “They should have just left the marketing to me, a board position or something like that,” says Sculley, “then Steve and I would never have separated.”

Jobs never spoke to Sculley again. “I believe he’ll never forgive me, and I understand him,” says Sculley. He looks tired. He is 71, a partner in a private equity firm, with an estate in Palm Beach, Fla., but after all these years he still suffers from Jobs’ withdrawal of affection.

Unfortunately, he himself was not talented enough “to build products or to look into the future like Steve,” says Sculley. In 1993, he had to leave Apple as well. The company was in a blind alley, devoid of ideas and without leadership, and therefore bound to lose against the new star of the computer world: Microsoft.

“Fortunately, Steve is there again,” says Sculley.

What makes him a genius, Sculley says, is Jobs’ ability to recognize, 20 years before everyone else, what will be standard in the distant future. “And Steve can do just that, he proved it with the iPod, he proved it with the iPhone, why shouldn’t he do it now in other areas as well?”

V. The Woman Who Understands The Man

“Steve is like all geniuses,” says Pamela Kerwin, “whoever said Mozart was a good person?” She laughs. And then she says: “Yes, he can be harsh and contemptuous, but he’s a visionary. And other managers want money and power, but he’s driven by the big idea. He has the ability to give birth to outstanding technology, and he’s never concerned with small steps – he wants whatever he makes to have a massive influence on the entire world.”

Kerwin is one of few women at the center of Jobs’ world. She is also one of the few people in his world who are able to take a reflective look at Jobs. She can say what she thinks of Jobs without falling into a state of shock, without fearing the withdrawal of warmth.

Things are pretty infantile in the Apple empire. Sometimes, a woman like Kerwin seems like the only adult there.

Perhaps it’s because she was never with Apple; Kerwin was from Pixar. Jobs took over her outfit in 1986 and then shook things up. Perhaps it’s because she was a teacher on the East Coast – a specialist in digital learning – before she came to Silicon Valley in 1989. She’s blond, wears glasses and a black turtleneck; she sits in the basement office of her house in Mill Valley, Calif.

Pixar, founded at the end of the ‘70s as a branch of George Lucas’ film empire, wasn’t yet one of the most successful studios in movie history, but one of several hundred startup companies in California. There was an idea, a handful of gifted people, parties and a lot of work. The grand old times. There was this uncertainty: Will we survive?

It’s not easy to create 3-D pictures. Pixar could do it, Jobs saw. “Back then, all of Silicon Valley said that he would sink his money into Pixar. He saw something that no one else saw. I think you could call that courage,” says Kerwin. Jobs gave Lucas $5 million and put up $5 million more for the company, and a journey began for the young people at Pixar.

Jobs hired creative types, but especially people “with developed left brains,” Kerwin says. Jobs didn’t really understand how the software worked. “When it came down to it, he didn’t understand what we were doing,” says Kerwin. “That probably protected us from him.” Certainly he yelled. Yes, he was punishing. He was moody. But he let animator and director John Lasseter, the main creative force at Pixar, take care of things.

Jobs sold Pixar’s services to Disney. “He could swim with the sharks, we couldn’t,” says Kerwin. “Steve wanted $10 million for everything he had to sell, always $10 million, even if it wasn’t worth $10 million.” He destroyed months of work. In negotiations with people from Intel, Jobs was in a bad mood shortly before the signing; Jobs swore, Intel was upset.

Kerwin says: “He’s not especially good at doing business with other important managers because then it’s ego against ego, and Steve never retreats, not even one step. But when he’s selling products to customers in jeans and a black turtleneck, like a messiah at these presentations, then he’s a brilliant showman. In that case, a big ego doesn’t interfere. An emcee needs a big ego.”

He changed Pixar’s direction: Animated pictures turned into short films, which turned into cinematic films. The screenplay for “Toy Story” was written, Jobs prepared the IPO. “Back then, all of Silicon Valley said this could never work, that a company that still hadn’t made a single dollar of profit was going on the stock exchange,” says Kerwin. “Toy Story” came out. Many years later, “Finding Nemo” followed. Those at Pixar who had made the journey with Jobs became millionaires.

And Jobs learned. He absorbed, took things apart, put them back together again, thought once more. He returned to Apple with the Pixar ideas. Animated pictures. Linking forms of communication. Mass media.

In August 1998, the iMac is introduced to the market. The response is tremendous, sales figures are great. But much more importantly, the fans are blown away. The Apple cult lives again. The slogan “think different” transforms Apple customers into allies, rebels against the mainstream, against Microsoft, fighting for personal individuality.

That’s the image, but it lies. Jobs is no longer a rebel: His company is about monopoly, market dominance. The next ruler always follows the revolution.

Jobs isn’t exactly a gentle person, according to all reports. He hates Bill Gates. Jobs was sick, perhaps he still is, and he hates his own young, healthy employees – in any case, that’s what young, healthy people at Apple say.

His natural parents are the Syrian political scientist Abdulfattah Jandali and the American Joanne Schieble; Paul and Clara Jobs adopted him. He grew up California, in Mountain View and Los Altos. Steven Paul Jobs was about 30 years old when he learned the truth. He began to look for his natural sister, Mona. He found her and they became friends. Then Mona wrote “A Regular Guy,” a novel. She told of a multimillionaire who “was too busy to flush the toilet,” who gave his ex-girlfriends houses so they would keep quiet; a narcissus who demanded that his lovers had to be virgins. Steve? It was never denied.

The Screenplay For “Toy Story” Was Written, Jobs Prepared The IPO. “Back Then, All Of Silicon Valley Said This Could Never Work, That A Company That Still Hadn’t Made A Single Dollar Of Profit Was Going On The Stock Exchange”

The actual Jobs was a fan of the folk singer Joan Baez. He said that he valued “young, superintelligent, artistic women.” In 1977, Jobs fathered a daughter, Lisa, with his then-girlfriend Chris-Ann Brennan. But they separated and he then refused to recognize the paternity. Chris-Ann and Lisa lived on welfare until Jobs was taken to court by the state for recognition of paternity. In a signed document, Jobs stated he was sterile and infertile and therefore physically incapable of fathering a child. The court forced him to take a blood test, which determined that he was the father; still, he refused maintenance payments. Finally, Jobs settled for monthly payments of $385.

In 1991 he married Laurene Powell; the couple now has three children.

A balanced life? Can a man who has this career behind him doubt himself?

About 10 years ago, Apple was worth $5 billion; today it’s worth over $240 billion. In 2006 Disney paid $7.4 billion in stock to acquire Pixar.

Vl. The Soldiers

Nobody at Apple wants to meet Jobs in the elevator, because then he’ll start asking questions: “Who are you? What are you working on? Why do we need you?” And when he gets out he’ll say: “No, we don’t need you anymore.”

Some teams always work in the spotlight – in other words, under Jobs’ eyes. These teams get all the resources and money, all the privileges in the world. But the spotlight wanders around campus. That means lively company politics, a lot of talking. Everyone wants someone’s attention, and everyone wants Jobs’ attention. But Jobs wants results; nothing but results really interest him. The best managers, the real heroes at Apple, are those at whom Jobs shouts most often – and who, in spite of that, speak calmly to their subordinates.

One employee who was there for a long time – until he got fired – is David Sobotta. He says that such uncertainty is “inherent in the system.” Sobotta sold what was developed in Cupertino. The Army, NASA and American universities were his customers. Today he lives in Roanoke, Va., high up on the mountains. “It extends throughout the company,” says Sobotta: “Nobody wants to decide anything, because a decision means that Steve can get mad. There’s a lot of dead meat at Apple.”

“Dead meat” being a cynical term for those people who could just as well be unemployed, and nobody would notice it.

“There Were The Golden Apple Sales Trips” – Trips To Paris, Sydney, Vienna, For The Upper 10 Percent, The Most Successful Sellers. With The New Leader, Everything Was Different. Better On The One Hand, But On The Other The New Leader Was Once Again Named Steve Jobs.

Sobotta says that it was once different; those were the years without Jobs. “There were the golden Apple sales trips” – trips to Paris, Sydney, Vienna, for the upper 10 percent, the most successful sellers. With the new leader, everything was different. Better on the one hand, but on the other the new leader was once again named Steve Jobs. Sobotta flew to Cupertino with generals and professors, but never once secured an appointment with Jobs, never received a promise that he would actually appear in person – always only a hint. “But the generals flew in, all of them wanted to be near Steve,” according to Sobotta. And sometimes Jobs appeared “in shorts and Birkenstocks, unshaven, and he never answered questions. He always just talked about the subjects he wanted to talk about. But the room heard him. Always,” says Sobotta.

Apple is a meeting company. They have meetings constantly, but nothing is decided. Then Jobs goes home. He goes to think. He has learned to trust his instincts; for years he’s been hearing that he’s a genius. For that reason, he’ll take showers in the morning and bury projects that he approved only yesterday. “No one knows what’s going to happen until the moment Steve goes on stage and addresses the faithful,” says Sobotta.

These are the moments of glory for Apple’s army. It’s all about these moments, for naturally the soldiers get paid well, but not outstandingly well; they get their pay plus bonus plus shares; they say that what counts are those fleeting moments in Jobs’ spotlight.

Jobs seldom names names on these occasions. He simply says, “This is the team that developed the iPhone. A round of applause, please.”

They stand up. They turn. Jobs nods and claps. That’s all they want, these five seconds, that’s what they’ve been working for for three months, 20 hours a day.

Could Apple be more successful if things were managed differently? With respect, with communication, like a modern company?

Since Jobs returned to Apple in 1997, the annual turnover spiraled up from a solid $7 billion to almost $43 billion. The share price rose from about $5 to over $260. In 2009, Apple made a profit of $8.2 billion. With 34,000 employees, that means a solid $240,000 profit per employee.

Thirty-four years after it was founded, Apple is no longer a computer manufacturer. It’s not very easy to say what Apple is, and somewhat harder to guess what Apple will be in the future: an electronics giant? An inventor of lifestyle products for the digital age?

How music is consumed, produced and sold today is different than 10 years ago. Tens of thousands of songs fit onto an iPod – a complete music collection in your pocket, always ready to be played. Large companies were brought to their knees because of it – because of iTunes, that is. Once Apple took over, music stopped being sold almost anywhere but through online stores.

The iPod turned into a phenomenon, into a “life-changing cultural icon” as Newsweek wrote three years after the device appeared; Apple had sold a good 3 million iPods at that point. In the past three business years alone, the company has sold 160 million units.

The Apple decade will come to an end. But that’s probably not the case. More likely, the coming decade will be even more successful for the company than the previous one, because Apple has the entertainment market within its grasp.

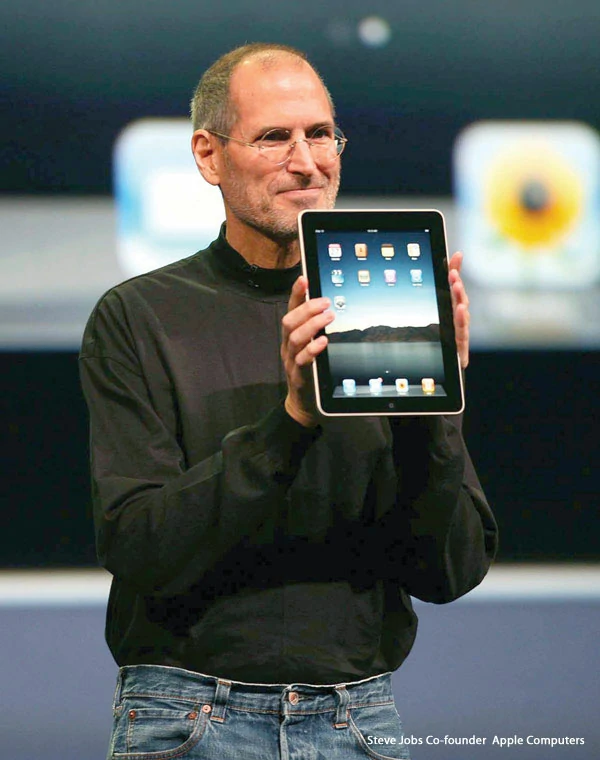

Now, with the launch of the iPad, publishing houses and media companies are racing to build something for Apple’s new gadget. They want to offer their books and magazines in electronic form on the iPad, a device Jobs naturally calls “magical” and “revolutionary.”

The iPad won’t just be a gift for magazines, newspaper companies and television corporations. They have high hopes of attracting new readers and viewers, and above all, endless new revenue. They all hope that money can be earned with old products, even in the digital age. Newspapers and magazines offer iPad applications for their print editions, with extras similar to those offered on their online sites: videos, interactive graphics. The intent is to lure readers into paying for digital editions, perhaps more than for the print edition.

All this in turn lures advertising customers, since they can make advertising more vivid and interactive with, for example, embedded videos. Time magazine is charging $200,000 for an advertisement in its first iPad edition.

But naturally Jobs knows all that – that’s the reason he developed the iPad in the first place. Jobs hopes to transform multiple branches of industry and bind them to Apple all at the same time. Apple will have a say in how a magazine looks so it can be read on the iPad, and how much money the publishing company will charge for this service.

Isn’t a new market dominated by Apple better than no market at all?

That may be. In any case, Jobs’ competitors say that Apple’s dominance will come to an end with the iPad, because the market will become so saturated with the company’s products. The Apple decade will come to an end. But that’s probably not the case. More likely, the coming decade will be even more successful for the company than the previous one, because Apple has the entertainment market within its grasp. And Apple is constantly growing, expanding as it always is into other, newer areas of modern life.

It is also possible that the company will continue on for a while longer and then, very abruptly, the iWorld will collapse. For good, if Jobs himself collapses and it becomes clear that his company isn’t prepared for life after Jobs.

The first time Jobs was absent was in 2004, it was due to pancreatic cancer. The doctors said the operation would save him and he would live at least 10 years longer. But Jobs hesitated. The pope of technology didn’t trust modern medicine. Jobs, a Zen Buddhist and vegetarian, preferred alternative methods. A diet, the pellets his nonmedical practitioner recommended. Jobs refused the operation for nine months, and during these nine months had discussions with the board of directors about whether he had to inform shareholders about the disease and methods of treatment.

But since the board is made up of people who revere Jobs, they said nothing.

On July 31, 2004, Jobs had the operation. On the next day he wrote an e-mail to employees: He had had a life-threatening disease, but now he was healed.

Five years later he was absent again. He needed a new liver, and naturally he got it quickly. From “a young man in his 20s, who died in a car accident,” according to Jobs. In the middle of 2009 the ruler returned to his empire, acting like everything was as before, but that wasn’t the case.

“It felt like late Rome,” says one person, who was there during those periods. Before Jobs was away for long, it was clear that no stable structures or rules existed: not for product development, not for communication. Was Steve’s thumb up or down? That was the only thing that counted.

But now, “The emperor was sick, and all the senators were arming their private armies and wanted power,” says the former employee, who would know. There were acts of vengeance: Those people who had come up with Jobs, lost their jobs and were excluded from all important discussions. “Products were announced and retracted, others were developed rashly and shot down again. Everything was company politics.”

Jobs was absent, and Apple employees were unsettled.

When the company has to carry on without Jobs, according to Hertzfeld, the Macintosh developer, then it would be better if at first it acted according to a plan. Customer needs could be taken into account; Apple could relearn things, like humility. After a while, however, Hertzfeld also says “the drive to create the best possible things would be missing.” And Apple would become a company like a thousand others.

The boss generally doesn’t like to talk about himself – in any case, he doesn’t say anything about his weaknesses. That time at Stanford, however, on a hot June day in 2005, when he spoke to students at the university stadium and made a speech that was like a confession, he finally told his third story: the story of life and death.

As a young man, Jobs said, he encountered a quotation: “When you live every day as if it were your last, you’ll be right sometime.” Since then, he has always asked himself whether he’s doing what he wants to do in case today is his last day. If the answer is “no,” he changes the plan.

He gulped. Then Jobs told Stanford that a year ago at 7:30 in the morning he was at his doctor’s office. The diagnosis: pancreatic cancer, incurable. He still had three to six months to live. “Get your personal affairs in order,” the doctors said.

“I lived with the diagnosis. On that same evening, I had a biopsy,” Jobs said.

The doctors inserted tubes, withdrew tumor cells, examined them. An operation could probably cure him after all. He was a rare exception, they said.

Is there a moral? There’s always a moral. “Your time is limited. Don’t waste it living someone else’s life. Don’t be trapped by dogma, which is living with the results of other people’s thinking. Don’t let the noise of others’ opinions drown out your own inner voice. And, most important: Have the courage to follow your heart and intuition. They somehow already know what you truly want to become.”

And finally he spoke his closing words: “Stay hungry. Stay foolish.”