It was almost a day of reckoning, at least an attempt at obtaining an iota of accountability and insight, when chief executives of six titans in banking on Wall Street testified before the US Senate Banking Committee in late May 2021 on their role as the COVID-19 pandemic hit America in 2020. The financial bosses presented a show of action in terms of lending, share buy backs, worker pay and their commitment to green energy. But in this well scripted presentation was the stark reality in the incongruences between paybacks and stakeholder interests.

The purpose of the Senate Hearing Annual Oversight of Wall Street Firms, in the words of its chairman, was to show Americans that their government is finally looking out for them; that the government understands that its economic system had betrayed millions of workers, and that it has and will continue to hold the country back. The Committee summoned the CEOs of the six biggest banks in the US to hear them say what they and their companies intend to actually do to change. They sought specifics; what concrete actions they will take to change the incentives on Wall Street, to reward work instead of wealth, and to undo the damage Wall Street has done, and continues to do, to communities of color, to stop investing in corporations that fuel climate change, threatening people’s communities and livelihoods and to channel their vast resources into businesses that employ actual people in cities and towns.

Within the framework of the primary objective of the Senate Hearing was the central thrust to examine the role of these leading financial institutions during the pandemic, their low levels of lending, despite their claim to the contrary, their approach to pay gaps between top executives and regular staff and their commitment to financing green energy. However, the hearing that was conducted remotely, once again highlighted the scourge in the financial services industry in the US where despite their overt commitment to support stakeholders and thereby the wider economy, the glaring contradictions that exposed their obligation to their diverse groups of stakeholders customers and employees – is not at the risk to their bottom line, CEO bonuses and paybacks to their shareholders.

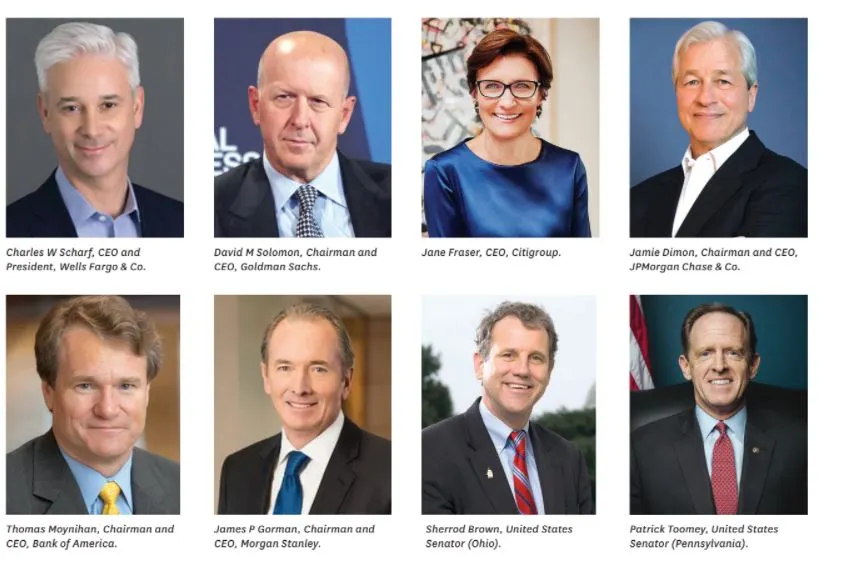

Interestingly, the presentations of Charles W Scharf, CEO and President, Wells Fargo & Co, David M Solomon, Chairman and CEO, Goldman Sachs, Jane Fraser, CEO, Citigroup, Jamie Dimon, Chairman and CEO, JPMorgan Chase & Co, Brian Thomas Moynihan, Chairman and CEO, Bank of America; and James P Gorman, Chairman and CEO, Morgan Stanley, focused broadly on their institution’s contribution during the pandemic hit 2020 and thereafter to change the existing trajectory that Wall Street has been accused of perpetuating; and this they had done by reaching out to the marginalized, low to middle-income groups, majority-minority businesses and women of color to offer credit, with an overarching emphasis on respecting diversity and focusing on racially marginalized groups, especially in assisting small businesses owned by people of minority groups and providing deferment and moratoria for struggling entities. Their figures in millions of dollars was indeed impressive, because these big banks, going by their data, had tied up with the Federal agencies to provide lending to the small business ecosystem, and also with businesses that serve underserved communities, thereby claiming to drive a sustainable and equitable recovery to the pandemic.

Right, these banks had done a fair amount of work during the pandemic in 2020, with commitment to continue their role in 2021, but the problem with them is that often they don’t respond adequately to issues concerning equity, often falling short of acting significantly to ensure parity. For instance, the chief executives with one voice agreed that capitalism was the best system, but the capitalism that these big financial institutions subscribe to in Wall Street contradicts the values and business practices that they were presenting before the Senate Hearing, because the “invisible hand” made up of people that make choices about the values and the society that people want to live in, an economy that is often dictated by the big banks and their lobbyists and the CEOs, was in fact for the benefit of their shareholders and at the cost to other stakeholders, which is in contradiction to the fundamental principles of capitalism. But, then the problem with capitalism is that it barely empathizes with social issues and social justice. There’s a good case in point. Citigroup’s top executive said that in the aftermath of the George Floyd killing, it launched billions of dollars to close the racial wealth gap in the US in its commitment to equity. Moreover, she said the fact that Citigroup holds itself accountable for and acknowledges where it has more work to do, sets it apart. But Citigroup was among several large US companies this year that asked shareholders to reject racial-equity resolutions and audits in the aftermath of the BLM activism and arbitrary killings.

In this backdrop, these executives were challenged. Notwithstanding the millions of dollars’ in deferred payments and waived fees for consumer and small business accounts, support for small businesses with lending to low and moderate-income and majority-minority businesses, that the skewed distribution of debt, drained wealth from the marginalized, thereby intensifying the racial divide and the gender gap. Albeit the contributions made by these banks to support business of minority groups, in 2020, the US had lost 440,000 Black businesses along with those of Latinos, and the Committee found that despite the very publicly asserted commitment, these institutions had an underlying reluctance to offer more to these communities’ businesses, constantly finding cover in regulatory justifications to not lend more to them. While the Federal Reserve had provided these banks with complete protection from overdraft fees, none of the CEOs present raised their hands when asked whether they had provided the same automatic protection to their customers and automatically waived all of their overdraft fees. What the Committee members felt was a need for these banks to step beyond the public messages of how much they do among communities and their stakeholders to bring about a systemic change to bridge the wealth gap in the country and to provide access to capital.

Good corporate citizenry and good corporate behavior in a capitalistic economy is for these companies to use their power to espouse good causes such as environmental protection and supporting sustainable initiatives, while reaching out to communities that face discrimination at the hands of the financial system, both private and state. As revealed at this Senate Hearing, often financial institutions complain the bane of relief programs given to groups that have the least access to resources, such as farmers, on their profits. As these executives were asked to distance themselves from the stand taken by the American Bankers’ Association’s claim that a farmer’s relief program would affect institutional profit, their responses were vague, alternating between a claim of not having read the letter or not being an issue concerning them.

The Committee heard that in the US alone two million families are at least 90 days late on paying their mortgage, millions of jobs lost and at one point the highest unemployment rate, with four per cent borrowers unable to pay mortgage. The banks have openly lent their support to the government’s proposal to extend their moratoriums for foreclosures and evictions until 2021. On the other hand, the banks while working closely with external groups and community organizations to encourage payment, in case of default, are prepared with a significant number of changes to work with.

The Senate Hearing also listened to detailed employee based initiatives taken during the pandemic, where employees were not laid-off, benefits extended, with provision for mental health support and paid family leave, costs of COVID-19 consultations, testing and health screenings being borne by employer; commitment to increase minimum hourly wages, time to care for family members or child care needs, and more importantly to maintain diversity in workforce. Despite the vocal articulacy concerning the value of employees and teammates, none would explicitly support if employees wanted to unionize. It was pointed that these very institutions don’t favor increments to employee wages. For instance, prior to the pandemic, the Bank of America had downgraded Chipotle’s stock value because analysts had determined that the company overpaid its workers; likewise, Wall Street punished American Airlines by reducing its stock value by five percent when it was announced that the flight attendants’ pay would be increased. Corporate leaders cry themselves hoarse that labor is being paid first and the shareholders the leftover. While it is imperative to reward talent, the Wall Street mantra is that the less you reward your workers, the better off you will be. What is overwhelmingly wrong with the system in the US, it was pointed out, is the underrating of workers as an asset. These big banks make decisions for employees far removed from their bases, living in faraway regions and whose reality they do not know and whose worth is grossly undervalued by Wall Street. The current system, pointed out Senator Sherrod Brown (D – Ohio), treats workers as a cost to be minimized – instead of the engine behind the country’s success. Then, the eloquent schemes that these CEOs say they have put in place for their employees sound a bit farcical.

These banks have committed to promote green energy initiatives as part of their sustainability agenda and commitment to be net zero emission by 2050. Clients’ transition to a low carbon economy will be supported by these banks. What is crucial in this transition process is to balance between energy policy and the economy and making sure that transition achieves both goals. In this light, the ethical financing of businesses was also highlighted at the Hearing with recent emphasis on financing green energy and ending financing to companies that do not follow proper environmental protocols. In the US, activists have applied pressure on the nation’s largest banks, such as to withhold offering banking services to certain types of businesses including energy companies and gun manufacturers among others. And many banks have responded by restricting credit and financing to such businesses. However, it was pointed out that restricting access to capital to law-abiding companies’ results in higher costs for consumers and slower economic growth. The executives’ response was that what dictated decisions pertaining to credit provision to companies is generally based on risk-based analysis. The banks’ representatives said that their commitment to green energy initiatives is evident through their carbon emissions that are published publicly, while they continue to be focused on wanting to have a constructive conversation about how they can improve emissions going forward. The point is will Wall Street undo the damage it has done? Will it stop investing in corporations that fuel climate change, threatening people’s communities and livelihoods?

The US is on a trajectory where everything has transitioned. Wages, machinery, and research, and new construction was where Wall Street funneled its capital decades ago. This was described as consisting of the ‘real economy’ of the US. Today, much of this is directed into stock buybacks, dividends, and complex financial instruments, with only about 15 percent going into the real economy. “Instead of investing in businesses that actually make things or provide useful services, and that create real jobs in towns all over the country, companies spend billions buying back stocks and handing out CEO bonuses. Stock buy-backs used to be illegal market manipulation. Today, they’re routine. Wall Street’s interests and Main Street’s interests no longer match up” (Senator Sherrod Brown). Finally, Patrick J. Toomey (R – PA), provides the prototype for what works in the economy – a three-way remit where “Business can only profit when they satisfy customers and that can only be achieved with a satisfied workforce and good relationships with the community.”