How many gifts did you give this Christmas to people you can’t stand, but have to keep sweet for the sake of your business? Richard Simon reflects on Yuletide in the Land of Waving Palms, and attempts to exorcise

It was the Saturday before Christmas, somewhere near the beginning of the Socialist Seventies: that era of queues, ration books and shortages which we all remember with such fondness. My father, then a branch manager at the Bank of Ceylon, was taking his afternoon nap, so when the doorbell rang, it was my mother who answered it. Standing on the doorstep was a man carrying a large, square wicker basket decorated with red ribbons: a Christmas hamper, no less. A gilt tag on the handle read WITH COMPLIMENTS FROM J- & CO. LTD.

“Mr. Simon’s house, yes?’ the man asked.

‘Yes,’ replied my mother, eyeing him dubiously. Is it important? He’s resting.

” No, no, madam, please not to disturb,’ said the man, smiling oleaginous. I came to give this only.”

He opened the hamper.

Inside was an Ali Baba’s trove of festive goodies: a rich, moist Christmas pudding decorated with holly, a breudher wrapped in red wax paper, an Edam cheese the size of a football, tins of Plumrose ham and Campbell’s soup and Scotch salmon and toffees and biscuits and of less interest to me at the tender age of twelve several bottles of which I remember only the distinctive tricom shape of Dimple Scotch. Nowadays you see such things in every supermarket, but at that time they were costly rarities, well beyond the reach of a junior manager in a State bank. I had stopped believing in Santa Claus a few years previously, but just at that moment I stood ready to revise my views. My mouth watered. I may even have drooled.

I could see my mother was tempted, too, but to my surprise she shook her head.

I’m sorry. I can’t take this,’ she said.

I was astonished. Why not? Hadn’t I heard her reminisce a thousand times about the days of her youth, when you could buy such dainties at Cargill’s or Miller’s or even at the Rupee Stores, Bambalapitya? Hadn’t I watched her driven almost to tears by the difficulties of making ends meet, especially at Christmastime? And now this wonderful, generous man had come to our door with a hamper full of her heart’s desire (and mine). Why on earth was she driving him away?

To my short-lived relief, the man wouldn’t take no for an answer. He argued. He pleaded. But my mother stood firm When the man tried to leave the hamper on the doorstep anyway, she yelled at him so loud he picked up his offering and scuttled off down the driveway. As the gate swung shut behind him, my father appeared, rubbing his eyes sleepily.

“What’s all the noise about? he asked. My mother told him.

Was it from he asked. She nodded.

“Good thing you shouted at him. The man’s a bloody crook. We’re still trying to get him to pay back a loan that was due last January. Says he’s broke, but he can find money to buy Christmas hampers. Wait till Monday, I’ll give him tight.”

My father died last year. He died poor, partly because he never accepted a gratuity in his life, nor disguised his contempt for those who gave and took them. But he died with a clear conscience, which is more than can be said for most of us.

And in this matter I am my father’s son, more or less. Oh, I’ll take a desk diary or a calendar for the servants if you offer me one, but I will make it clear that my acceptance does not oblige me to do you any favors in return. And for the an-

nual mercantile-sector ritual of offering bankers, bureaucrats, politicians, fixers and clients tasty bribes thinly disguised as gifts, I have-as he had-only contempt.

Most of my adult life has been spent in advertising, an industry in which the giving and receiving of presents with strings attached is practically an institution. In the weeks preceding Christmas, the media departments of most ad agencies begin to resemble the back room at Victoria Stores, with bottles-liquid incentives for scheduling and production staff at the newspapers, television and radio stations-piled up to the ceiling. Downstairs in the art studio the boot is on the other foot, as every supplier of magic markers, spray mount, stationery and all the other paraphernalia of the craft tries to make sure the agency places its orders with him next year. Want a diary or calendar? Want a dozen? Just ask the print production manager, whose cubicle is so full of the things he has to sweep them off his chair before he sits

down. Their annual abundance or scar city is as good an indicator as any of how well the printing industry has done that year-the leaner the year, the more numerous the diaries.

The currency of goodwill in the advertising industry is, however, small potatoes compared to what a banker can make if he’s willing to extend credit periods indefinitely or relend to a known defaulter. Many of my father’s colleagues drank whisky all year round. Not a few of them had expensive cars or comfortable houses, registered in the names of their wives and grown-up children, purchased with their ill-gotten gains. They thought my old man was a fool because his hands were clean and his pockets empty. From their own crass, money- grubbing point of view, they were quite right.

But did the givers really get their money’s worth? I wonder. When the squeeze is on and the choice is between you and his job, the world’s most corrupt credit officer is going to start calling in

the dues and won’t take no for an answer. It’s the same in every other field, too. When you’re struggling to make a late press insertion, the memory of last year’s giftie is hardly enough to make the newspaper’s scheduling manager bump someone else’s ad and run yours in its place. The gold-plated Cross pen you sent your biggest customer won’t ensure he places next year’s order with you when your prices have gone up eight percent and your competitors’ have stayed the same. On a more mundane level, the bottle of arrack you gave the municipal garbage collector is no guarantee of a year of promptly collected trash and well-swept streets-far from it. Once he’s salaamed his hypocritical gratitude, drunk up the booze and slept off the hangover, you can whistle for service-until the same time next year, when it briefly improves in anticipation of yet another round of ‘presents.

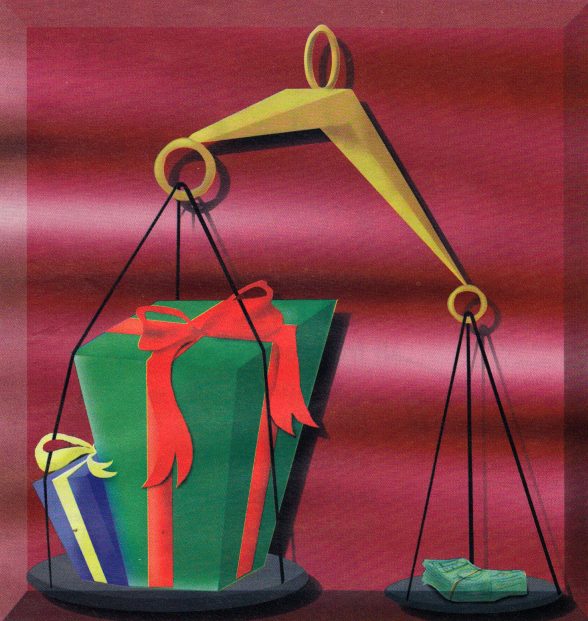

Don’t forget, you’re not the only giver. The recipient of your gratuity is being showered with similar gifts from all your competitors. What makes you so special? The quality or value of your gift? Forget it. Start trying to out-give everyone else and you’ll find yourself in a contest. whose ultimate conclusion is exhaustion and bankruptcy. No, the best you can hope for is to maintain parity with your competitors, thereby keeping the playing field level for one more year. Once the wrapping paper comes off, everybody’s back to square one.

So why do you keep on giving?

Surely not out of the goodness of your heart, or from the irresistible pressure of seasonal goodwill. Oh no. You keep on giving because you know what will happen if you stop.

Your orders will dry up.

Your credit will go bad.

Your ads will disappear from the media.

Tour groups will avoid your ho tel as if it’s a plague zone.

Your licenses will be revoked.

Your vehicles will be repossessed.

Your telephone will go dead.

Your front yard will turn into the town dump.

And your wife will leave you for a man with a firmer grasp on the realities of life.

So you keep the handouts flowing, and what does that make you? The soul of generosity? A smooth operator who

know how to grease the wheel?

No. It makes you a victim of institutionalized blackmail.

I have argued before in these pages that corruption is not, as some people like to think, the preserve of a few bad hats, but is deeply woven into the fabric of our society. The annual ritual of gifts-for-favors is yet another manifestation of this unhappy truth. One day, perhaps, things will change, but for now things just change hands. For the little guys, the little things: bottles of cheap booze, one-sheet calendars, key tags, branded ball-points. For the men and women in the middle, desktop bric-a-brac, hotel weekends, Chivas Regal and French rag dolls wearing t-shirts that assert that you mean a lot to them (you do; in the giver’s eyes you’re next year’s meal ticket). Fatter cats get fancier prezzies: Cartier watches, plane tickets, golf club sets or sexy lace panties with the former owner still inside them. For the lucky few at the summit of this mountain of iniquity, the ‘gifts’ are contractual kickbacks worth millions.

Where will it all end? Maybe there’ll come a day when we dispense with money altogether, and pay each other in goodies instead- a return to the days of the barter economy. Perhaps the government will levy a prohibitive tax on Christmas gifts and save us all from our selves, although I doubt it many of our legislators are as keen on a handout as anyone else, and are unlikely to do anything that might stanch the flow.

If we want to clean up this particularly unsavory aspect of the festive season, we’ll have to do it our selves. By the time this article appears the New Year will have come and gone, but perhaps it won’t be too late to make one more resolution. Let’s all decide that, come next December, we’ll sell out to the blackmailers as we have always done-how could we do otherwise?-but that, no matter how strong the temptation, we won’t take anything ourselves. We’ll be out of pocket, but we’ll feel a lot better about ourselves and best of all, we’ll have broken the chain, so that when the last Christmas of the millennium rolls around, nobody will have to give anyone anything for any reason other than the only really worthy one: honest affection for the recipient. And Dackly, this one’s for you.