A middle-aged lady walks into a shop. The shop assistant is on the phone to a friend, having a good old gossip. Patiently, the lady waits to be served, but the assistant doesn’t even look at her. At last, in exasperation, the lady raps on the counter. This annoys the assistant. What do you want?” she asks rudely. The lady tells her. We don’t stock that,’ replies the assistant, and goes back to her conversation. The lady, who has waited ten minutes for nothing, leaves quietly. What else is there to do? In a government factory, employees discuss the upcoming privatisation. Under State management, salaries and designations were based on seniority, but the new private owners plan to put a stop to that. From now on, both remuneration and promotion will be tied to performance. The angry workers vow to do everything in their power to oppose the privatisation. Angriest of all are four hundred ‘surplus’ workers, hired several years ago, who still have neither duties nor job designations. Soon, a strike is brewing.

•At a privately-owned machining plant, a rejection rate of 50 percent of finished components is knocking selling prices up to uncompetitive levels. The owner knows what’s wrong-shoddy work on the production line. He tries every trick in the book to motivate his workers, but to no avail-and when he tries to fire one of the worst offenders, he finds himself with a nasty Labour Tribunal case on his hands. In the end, he relaxes the stringency of his quality control measures, letting inferior products go to market. He knows it’s bad for business, but he has no option.

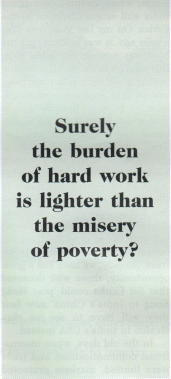

•At a hotel in Kandy, the second phase of a project to assist poor farmers is being planned. In the first phase, various farming methods were tested; in this phase, the successful ones will be taught to farmers. But some of the most promising methods of all will not be taught. Why not? Because, the project staff explains, ‘the farmers find them too hard’. The foreign donors funding the project are dumbfounded. Surely the burden of hard work is lighter than the misery of poverty? ‘In this country, things are different,’ the European project manager informs his compatriots from the home office, while his Sri Lankan colleagues hang their heads in shame.

Yes, indeed: in Sri Lanka things are different, and they seem to have been different for a very, very long time. Sir Thomas Maitland, British Governor of Ceylon be- tween 1805 and 1811, told acquaintances that ‘there was no inhabitant in that island but would sit down and starve out the year under the shade of two or three coconut trees…rather than increase his in- come and his comfort through manual labour.”

A colonial governor’s views regarding his native subjects may be taken with a grain of salt, but Maitland’s words do have an uncomfortable ring of truth. Even today, two centuries after they were uttered, the attitude they describe seems as widespread as ever. Productivity experts bemoan Sri Lanka’s pathetic industrial output and per-capita GNP. Plantation managers compare annual harvests per acre with those of other tea-producing nations, and weep. The machinery of national administration operates as if immersed in molasses. Sri Lanka, it seems, just doesn’t work.

Why not? There are as many explanations as there are self appointed pundits to provide them. Foreigners, for example, like to put our legendary indolence down to what might be called the Tropical Paradise Syndrome. Sri Lanka, they tell us, is a land of plenty, where the fruit drops off the trees, the fish jump out of the sea, and the wonderful climate make clothing and shelter almost unnecessary. In such an Eden, how could anyone possibly develop a work ethic?

Traditionalists, conversely, blame the foreigners. According to them, all our troubles are caused by invaders and imperialists. However, the traditionalists cannot seem to agree on which set of foreigners to blame: was it the Cholas and Cheras or the Parangtyas and Landesiyas? No doubt the all-conquering British had a hand in it. And what about those evil Americans who are even now polluting the morals of our youth with born- again Christianity, Music Television and Coca-Cola? Next pundit, please.

Leftist intellectual types, the ones who inhabit think-tanks and NGO offices, hate to admit that a problem of national inertia exists at all. To do so would spoil a certain image of the Heroic Worker cherished by those who have never flexed a biceps in earnest. If productivity is low in Sri Lanka, they tell us, it is not the workers’ fault; exploitative governments, employers or landlords are the culprits, or perhaps the national. system of education and vocational training is to blame.

The scientifically minded point to poor nutrition and enervating diseases such as malaria and filariasis which sap the energy of the workforce. Bureaucrats blame the politicians for encouraging idleness with favouritism and handouts. The politicians themselves have the simplest explanation of all-obviously, other politicians, from the opposite camp, are the villains.

No doubt all these factors contribute to the overall result, which is that Sri Lanka is a place where nothing ever gets done properly, and only rarely something gets done at all. But people in other countries have faced and overcome any number of similar handicaps; why can’t we? Anyone who has travelled or worked abroad well knows how lethargic the pace of life in Sri Lanka is compared to just about anywhere. else. It isn’t the cause that matters, but the effect. Our efforts to explain our unlovely idleness are nothing but desperate casting about in search of excuses for all the clock-watching, short-leave- taking, sick-note-forging, weekend- extending, buck-passing, upward- delegating and just plain nothing- doing to which we are so prone.

Most of us have heard the story of how our country used to be held up to the people of Singapore as an example of what they might achieve if they were willing to work their butts off, and how, for thirty-odd years, they worked said butts to such excellent effect they not only achieved their goal but considerably surpassed it, while we for our part went backwards. It’s a sorry tale, one that puts us to shame. And-tremble, ye lotus-eaters!-it is happening again, much nearer home this time.

For decades our giant neighbour India lay sleeping, stupefied by bureaucracy and outmoded Socialist policies. But now she has woken up, and already she is outpacing us. When I first visited Bombay in the early Eighties I could afford to be smug about what I saw; at home we had TV, computers, a booming economy and shops crammed with consumer goods, while teeming, struggling India still seemed trapped in the Fifties. On my last visit, just over a year ago, it was evident that the boot was now on the other foot; this time I was the country cousin, paying a call on a relatively prosperous and sophisticated neighbour. From Bangalore to Bollywood, India is racing to embrace the twenty-first century. True, the subcontinent still includes some of the world’s most backward places, but in the big cities and the populous states of the western seaboard you can see the beginnings of an economic tidal wave that could swamp us on our little island as we lie dreaming beneath the shade of those palm- trees. Already, we have lost a great opportunity; those who dreamed that Sri Lanka could ‘play Hong Kong to India’s China’ now fear they will have to see us play. Mexico to India’s USA instead.

In the old days, when international communications and trade were limited, markets protected and national borders really meant something, Sri Lankans could afford the luxury of taking things easy. Our standard of living might suffer, but as long as we could shut out the rest of the world, our society would remain intact. Nowadays only a fanatic or a fool would argue that such a course of action (or rather, inaction) is possible. There are no islands any more- all countries are contiguous. Unless Sri Lanka can compete internationally in this jostling, deeply interdependent milieu, she will not be able to sustain her domestic economy. And if her economy collapses, how will her social institutions survive? And when they founder in their turn, what will happen next? Any student of history can supply the answer: anarchy, followed by tyranny, foreign conquest, or both.

If we love our country, we had better start working. All of us Together.