June 13, 2024.

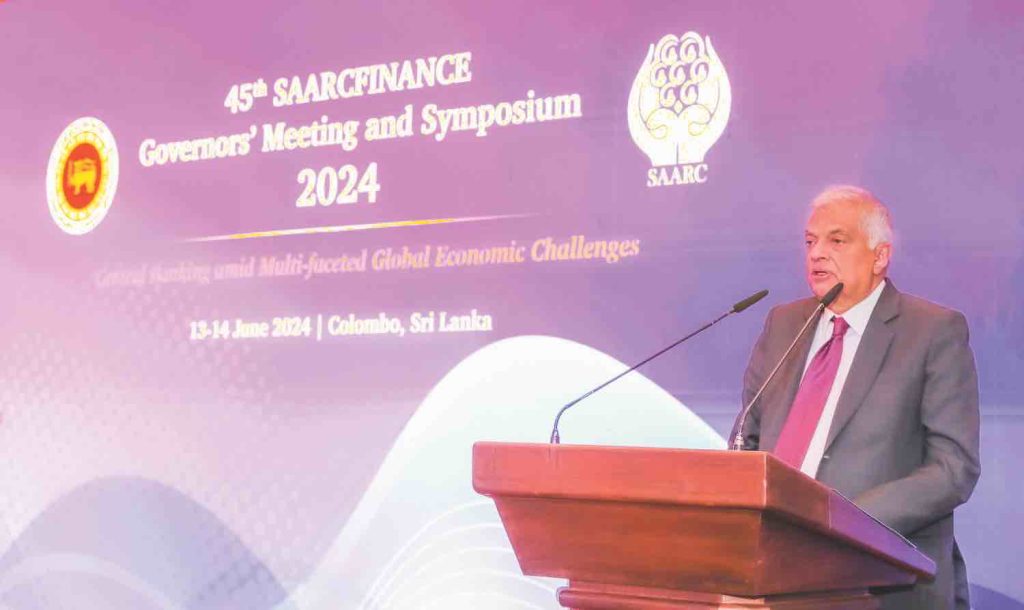

President Ranil Wickremesinghe with officials at the 45th “SAARCFINANCE” Governors’ Meeting and Symposium.

“The work we have been doing in the last two years when many people didn’t expect Sri Lanka to come out of this crisis so quickly, has been remarkable,” President Wickremesinghe stated. He attributed this success to the dedicated efforts of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka, which played a crucial role in guiding the nation through challenging times by enforcing policies that curbed expenditure. He also expressed gratitude to the Government and Reserve Bank of India and the Government and Central Bank of Bangladesh for their financial support, which he described as lifesaving. This assistance and aid from USAID and the World Bank were pivotal in stabilizing the country’s economy.

President Wickremesinghe outlined plans for Sri Lanka, including introducing the new Central Bank Act to ensure monetary stability. He also mentioned upcoming legislation, such as the Public Debt Management Bill and the Public Finance Bill, which are expected to bolster financial and monetary stability in the country.

The President underscored the importance of combating corruption and detailed the government’s commitment to establishing a robust anti-corruption framework by 2025. He also highlighted the need for job creation and economic growth, stressing the importance of transforming Sri Lanka’s import-based economy into an export-driven one.

“As the Governor mentioned, we had good news. It was better than what I anticipated because reading briefly, we’ve been saying performance under the program has been strong. All quantitative targets for the end of December 2023 were met, except the indicative target on social spending. Most structural benchmarks due by the end of April 2024 were either met or implemented with delay.

The work we have been doing in the last two years when many people didn’t expect Sri Lanka to come out of this crisis so quickly, has been remarkable. I was confident, and I am fortunate to have had a team that shared this confidence. I must acknowledge the role played by the Central Bank of Sri Lanka in guiding this group, especially under challenging circumstances. They upheld policies requiring a curb on expenditure, something unfamiliar in Sri Lanka for a long time.

I must also extend my thanks to the Secretary and the Ministry of Finance members, who, along with the Central Bank, were responsible for formulating the policy and handling the pressures of budgetary restrictions that the Central Bank did not have to face.

Additionally, I must thank the Government, the Reserve Bank of India, and the Central Bank of Bangladesh. The three and a half billion and 200 million were lifesavers. Without that, we wouldn’t be here today; there would have been chaos.

Their support allowed us to obtain some fertilizer, which we received as aid from USAID and assistance from the World Bank. That was a challenging year. I won’t delve into it here; it deserves a book, not merely one hour of discussion.

Today, you are meeting to discuss central banking issues amid multifaceted global economic challenges. This topic requires in-depth discussion for this region. I need not elaborate on the role of monetary policy since the 2009 crisis and the necessary measures to recover from COVID. You are also facing two issues: where does the power lie in Montreal—is it exercised by the IMF with the present voting pattern? If not, what’s the challenge that the BRICS can pose? These are concerns for all of us, and South Asia should take a similar stand, especially with the move towards de-globalization after years of being urged to globalize. What happens to the international monetary system? But I will not go into detail on those.

I thought of speaking a few words about what Sri Lanka has achieved and what we plan to do in the coming years. To illustrate the depth of the crisis, let me provide a few facts. I was born in 1949. The fixed exchange rate at that time was three rupees 32 cents. In 1978, when I was in the Cabinet, we did away with the fixed exchange rate and moved to a floating exchange rate of 16 rupees per dollar. By 2009, we had reached 116 rupees to a dollar, despite expansive schemes like the Mahaweli Development Scheme, which required money printing. The IMF stated there was a moderate risk of external debt distress.

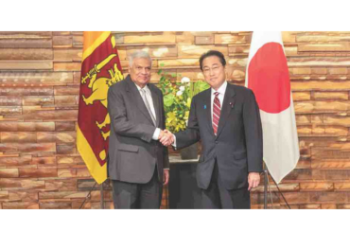

President Ranil Wickremesinghe.

After 2009, the war was over, and the Mahaweli Scheme made us self-sufficient in rice, saving foreign exchange. Our free trade zones ensured our manufactured goods were exported, and we had a thriving tourist industry. By 2024, people expected the rate to reach 400 rupees per dollar. Today, it’s at 300 rupees. So, the story from 1949 to 2024 highlights that the economy’s growth often relied more on printing money than on central bank policies. As a borrower, we either borrowed money or printed it.

Fortunately, I was in a good position because my family was involved in printing, so I understood its limits. The new Central Bank Act, which we have presented, aims to ensure monetary stability. The central bank cannot grant credit to the government. There is no way to obtain loans from the central bank, nor can money be printed or taken from the state bank. This forces us to look at how to raise revenue. Additionally, there are inflation targets. We have three laws: the Central Bank Act, the Public Debt Management Bill, and the Public Finance Bill, which Parliament will pass. These will form the framework of our financial and monetary stability. Once we carry this through, I see Sri Lanka achieving stability in monetary and fiscal affairs for the next decade or more. The second issue is corruption. Corruption has been a significant issue in Sri Lanka, and everyone talks about how to address it.

We need to find out how to catch them. That’s the problem. So, my government has agreed to discuss the matter with the IMF. We also required their help, and we brought the governance diagnostic report. Many laws have to be passed. One has been passed, the Anti-Corruption Act. The second one, proceeds of crime legislation, is now being drafted and sent to Parliament. There are a series of other laws that are required. By 2025, we will have the strongest anti-corruption system in South Asia and even, I think, in Southeast Asia, except for one or two countries. So, this brings us to the next part of the issue. Now we have stability. The next issue is the one that worries all politicians: jobs. How do you create jobs?

There are a large number of people in our country who expect jobs. As the level of education goes up, they are not satisfied with just a menial job; they expect satisfactory jobs. In our country, virtually everyone has a mobile phone or two at most. But what is the expectation of a job? We have to realize that our per capita income also has to increase as we find jobs in this area. This is also a growth area. I read some reports and like to read from them. One World Bank report on growth for 2024 states that growth in South Asia is expected at six percent for 2024. It’s one of the highest, but structural challenges hinder the ability to create jobs and respond to climate shocks. Are we going to get stuck with jobless growth, destabilizing the system? Or are we looking at growth?

This is what I thought we should address in Sri Lanka. We are all in this traditional British system where we don’t address the significant policy changes required. We pass various enactments creating one authority or abolishing it and creating another one, but the total framework is not created by us. In many other countries, you find specific laws on economic development and regulating the financial system. We still need to get that. We stick with the British policy of not doing it. Britain accepts a free market economy. We are in countries where it’s all debated: Do you want a free market economy, a socialist economy, a Marxist economy, a controlled economy, or socialism with Chinese characteristics or Vietnamese characteristics? We just can’t make up our minds about what we want and what our goals are.

Let us bring in the third part of the legislation, which is the most important to me: How do we ensure economic growth? What do we do? For Sri Lanka to grow, we must transform our import-based economy into an export-driven economy. The IMF report says, “Nevertheless, the economy is still vulnerable, and the path to debt sustainability remains knife-edge. Sustaining the reform momentum and efforts to restructure debt is critical to putting the economy on a path toward lasting recovery and debt sustainability.” As a result, we have decided to bring a new law called the Economic Transformation Law.

From British rule onwards, we’ve had laws that created a colonial market economy dependent on plantations. 1972, there was a breakup of capital formation and a strictly controlled economy. In post-1977, we started gradually liberalizing, but we did not bring the necessary legislation. A series of legislation brought in the 1972 economy, but we were chipping away after that. Each time we chipped away, there was some demonstration outside or a campaign against it. Nevertheless, we chipped away. Let’s put the new economy into place. We have failed; there’s no need to be shy about what you are doing. Do it and be done with it. That’s what Erhard did in Germany, what the Japanese did after the war, what the Chinese did, and what the Vietnamese did. There’s nothing to be frightened of.

I have not in any way departed from the principles of our democratic socialist system. In fact, I have incorporated two of its objectives: to ensure that all citizens have an adequate standard of living and to create rapid development of the whole country through public and private economic activity geared towards social objectives and the public good.

First, I made it clear in the law that I am working within this constitution. No one can say that I am going outside the objectives of the constitution. These two provisions are more than enough to rewrite Sri Lanka’s economic policy. It has to be growth-oriented; others have failed.

In clause three, section three, I put down that the national policy on economic transformation must provide for the restructuring of the debt owed by the government. The public debt to GDP ratio shall be below 95 percent by 2032. These are IMF targets. The central government annual gross financing needs to GDP ratio shall be below 13 percent by 2032. Now, that is in the law. That is what we agreed with the IMF. The central government’s annual debt service in foreign currency to GDP shall be below 4.5 percent by 2027 and after that. This is one part of the national policy on economic transformation, which includes some of the factors to be considered in the national economic transformation.

The second part is the transformation of Sri Lanka into a highly competitive, export-oriented digital economy. This legal obligation includes diversification and deep structural changes in the national economy to boost competitiveness. The law states that we must have deep structural changes. I would like to know if anyone can go to court and take action if we don’t have deep structural changes. Achieving net zero by the year 2050, increasing integration with the global economy, achieving stable macroeconomic balances and sustainable debt, modernizing agriculture to boost farmer productivity, incomes, and agriculture exports, and promoting inclusive economic growth and social progress are also part of the plan.

In formulating the national policy on economic transformation, the cabinet of ministers must ensure the following targets: GDP growth to reach five percent annually by 2027 and above five percent thereafter. Unemployment should be below five percent of the labor force by 2025. Female labor force participation should reach at least 40 percent by 2030 and at least 50 percent by 2040. The current account deficit of the balance of payments shall be at most one percent of GDP annually. Exports of goods and services as a percentage of GDP should reach 25 percent by 2025, 40 percent by 2030, and 60 percent by 2040. Net foreign direct investment as a percentage of GDP should reach not less than five percent by 2030 and not less than 40 percent after 2030.

The primary balance in the government budget should reach 2.3 percent of GDP by 2032 and at least two percent from 2032. Government revenue should go at least 15 percent of GDP beyond 2027. The multidimensional poverty headcount ratio should be less than 15 percent by 2027 and ten percent by 2035.

These are difficult targets, but you need to make it difficult to succeed. If a government feels it can’t achieve this, it must go to Parliament and amend the act. Otherwise, it would help if you acted within this framework. This is opening up the system entirely, and that’s what we are aiming for. It also means that, as I have done earlier, we all work together. I meet with the governor, my economic advisor, and others weekly. But it means that we can now put together a mechanism. A legal mechanism has to come into place, either by cabinet vision regulations or by law. The central bank, the treasury, and economic advisors are working together to achieve this objective.

First, I want to ensure that the initial beneficiaries of the measures we have taken with the IMF are the ordinary people of Sri Lanka. They are the ones who suffer the most. They are the ones who lost their jobs and had to mortgage their properties and sell their land. To ensure that, we should ensure the money goes to the bottom. Stabilizing the rupee and bringing interest rates down has been one benefit. With the help of the World Bank, we have increased social welfare payments threefold. From 1.8 million families, it will go up to 2.4 million families. That’s at the very bottom. We gave government workers a 10,000 rupees allowance, and the private sector followed. The government ordered plantation companies, which had refused, to pay 1,350 rupees per day. It was a challenging course, and the court threw out the challenge. So we have ensured that money goes in.

We also created a district development budget. These are decentralized funds to build roads in villages or buildings, which means giving money to small contractors and others in the area. A fair amount has been given to the people. Since 1935, the government has been giving out the land for people to cultivate, but never ownership, only through a permit. Similarly, we have built houses for low-income families in and around the city of Colombo, which are again given for rent. We took a policy decision, which we are implementing now, that all lands given to average people for building houses or for cultivating will now be given as freehold land. We will provide title deeds to those with these low-income apartments, which means two million additional families will get this money. These are bankable assets, so look at how the banking service expands and how you take it to rural areas.

We are also bringing in new laws to change vocational training because many people go into vocational training more than university students as they look for employment. These are some of the measures we are taking to ensure that the lower end of the population benefits from the measures we take. It cannot be confined to a few at the top. We want the big companies to expand, and I’m happy to see many growing. We already have hotels in the Maldives and are now investing in Bangladesh. We are seeing Indian investments coming into Sri Lanka. As we expand, we can deal with the economic issues relating to collaboration. We are at a very significant moment. Many countries have held elections, and new governments have come in.

In Sri Lanka, we are going in for elections. Expectations are high. Is it going to be the usual way to change the government every five years, or will we deliver? The central banks have a major role to play in this.”

President Ranil Wickremesinghe with Shaktikanta Das, Governor of the Reserve Bank of India (left) and Dr. Nandalal Weerasinghe, Governor, Central Bank of Sri Lanka (right).