Arthur Hadley

Arthur’s caught, taken in by the temptation of living an alluring online self, straying in the nether regions of a strange world outside and beyond our real world. He is a prisoner of the network making an ardent plea for release. Who can save him?

H I MY NAME IS ARTURO 8729@STL COM. I’m a nice enough guy, I guess. I have a lot of interests, most of them superficial, but so what? I like to surf. I enjoy chatting. I get mail and always answer it. Occasionally I spend a couple of hours downloading: who doesn’t? It’s something to do. Well, it is true that I keep pretty weird hours, into midnight often, but there’s no law against that. I admit I am not as interesting or cool as some of the computer wizards around in my outfit. I haven’t spent hours constructing a page or anything. I don’t know STL. Call me stupid. But when it comes to online persons, I am as good as any and no worse than most. I don’t think I deserve what’s happened to me that’s for sure.

I’m so lonely.. Let me out! Help! Sorry, I promised I wouldn’t get emotional, that I would explain what’s happened to my virtual self and perhaps persuade you not to take the sorry road that I’ve traveled. It’s possible that it’s too late for me. But it might not be for you.

Here’s the story from the beginning.

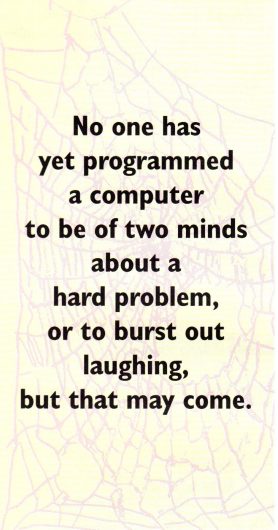

can make computers that are almost human. In some respects they are superhuman, they beat most of us at chess, memorize whole telephone books at a glance, compose music of a certain kind and write obscure poetry, diagnose heart ailments and stomach problems, even go transiently crazy. No one has yet programmed a computer to be of two minds about a hard problem, or to burst out laughing, but that may come. Sooner or later, there will be real human hardware, great whirring, clicking cabinets intelligent enough to read magazines and vote, able to think rings around us.

But the bottom line now is that once you become an online person, you are trapped, you are in the grip of something that you cannot control, you are controlled. Before we begin organizing sanctuaries and reservations for our software selves, lest we vanish like the dinosaurs, here is a thought to contend with.

Even when technology succeeds in manufacturing the perfect machine to do everything we recognize as human, it will be at best, only a ghost of our- selves. As soon as we become an online person you end up a prisoner, a ghost.

It was so exciting at first when the affable, hulking beast of a guy MAHESHWARAN lured me into this place with a promise of fun and relaxation, all for a low monthly price. It would cost you a few thousands otherwise, he said. “The first month is free!” he said, and god help me, I went and now he’s got me trapped in here, and I can’t get out.

It’s cold here in STL and gray and dark and smelly. It’s crowded with the ghosts of other online personas, long since abandoned by their nonvirtual selves. Quiet desperation, that’s what you see around these parts.

It was so much different at the start when we joined. It was easy then. Mahesh was all over us, telling us how we should get about doing things and offering us the latest diskettes to use as aids. So that is how Arturo came to assume his online self, to be born. I liked my name, even though I wished I didn’t need the numbers at the end. And at the beginning we had a lot of fun. I don’t have to tell you how it was. The surf was cool. The data modem was warm.

Many times we spent the entire night together. These were the best times.

All good things have to come to an end, things. soon began to change. And all of a sudden you couldn’t walk around here. All kinds of new types showed up. I don’t want to disparage them, but let’s just say a lot of them weren’t our kind of persons. They wouldn’t know what to do with themselves a lot of the time. They just sort of hung around aimlessly as our so-called public servants in government offices are often seen doing. The hell with it. They have as much right to be here as I do. But now I began to notice that Arthur started reaching me less and less. I asked the system operator Nalaka about it and he just shrugged and looked at me blankly. May be it had something to do with the fact that he was besieged by hundreds, perhaps by thousands, of other persons clamoring for some kind of explanation. It was just like the time recently when operators badgered for information at the Hilton after the latest Tiger bomb blast. My online companions, however, were like me thin and ragged and desperate for some kind of human contact.

Time has flown by, it’s months since I’ve heard from Arthur. Some nights I hear him outside the walls of the prison Maheswaran has made, mashing his fist against the heavy metal doors, trying to break in and get me out, cursing and pounding the gateway, over and over again being denied access. The line is busy they tell him.

It’s kind of sad really. We belong together. We in Mahesh’s prison are like zombies, much like the zombies in LTTE brigand leader Prabha’s prison. Like us they are trapped, they are hypnotized, mesmerized, their minds numbed within, reacting like drugged beings, human machines follow- ing the behests of a manic master machine. What do I do? What do we do? We’ll never walk free through this cyberspace again. Mahes won’t let us. Prabha won’t let his zombies go and even if they do they will be lost in the Wanni, poor lost souls, like us. Poor Arthur!

On the bright side or is it the dark side? Mahesh won’t let us quit altogether. He’s holding us like the bandit bombers who held those they could grab as hostages. There’s simply no way anyone from the real world can contact Mahesh to complain and get Arthur online dumped out of the system. When someone actually tried to get to him by contacting another nonvirtual person, it took ages. Then that person was rude and peremptory, and all he said was that Arthur was fine and comfortable where he was and his peace shouldn’t be disturbed. Oh dear! Ha ha ha.

Now I – Arturo- want so much to be with the real Arthur. We are so much a part of each other. I have mail for him. Messages from new friends he had made, who now believe he doesn’t care to hear from them, from old acquaintances from college, business associates, his brother and even his wife. To make matters worse Arthur’s being slandered on the Net. They say there’s no more privacy on the Net. But Mike Godwin, staff counsel for the Electronic Frontier Foundation (reported in ‘Time’ magazine) says people can say bad things on the Net and circulate them to a million of their closest friends. Yet he’s all for the Net, calls it a level playing field. He believes that if someone defames you, you can get online and fight right back. Poor Arthur, he’s got to do it all by himself, perhaps with a little help from me if Mahesh will allow it!

So at least we’ll be together, Arthur and I, in some mysterious way, forever. I day-dream sometimes as I lie here rotting away with the rest of the poor online souls. I dream of an open place where people roam free with their virtual selves in tow, exchanging pleasantries, skipping lightly over the vast expanse of banality and infobabble that swims everywhere in the ether.

The sun is shining, and the crisp, sharp crackle of successful modem connections fills the air with the electric glow of human potential declaring itself. Me, and Arthur, we travel together around this bright and engaging landscape, learning, probing, sometimes pretending to be other people, communicating. Virtual life is good. Then I wake up and find myself in here, alone, jammed cheek by jowl with the ever growing ranks off disembodied online selves. Who can blame me for despairing?

Look! Here comes more of them! Lured by Maheshwaran into this dank and horrible dungeon by the easy 800 number that delivers them to this door, seduced by the promise of unlimited access for one easy flat rate, paid in advance at the end of the previous month! Go away, you guys! There’s no more room in here! I don’t know what the marketing weasels told you, but we don’t have the infrastructure to support any of you! You’ll die in here! Please, Mr. Mahesh! Have Mercy!