Dave Ulrich and Norm Smallwood

THE LEADERSHIP CODE AND LEADERSHIP BRAND

The RBL Group © 2009. This article was first published in the AMA Handbook of Leadership

If you Google the word leader, you get more than 300 million hits. On Amazon, there are 480,881 books today that have to do with leaders as the topic. It doesn’t help to go to Wikipedia to get a clearer definition because right off the bat they define 11 different types of leaders from bureaucratic to transformational to laissez faire. In the field of leadership there are as many opinions as there are writers and there is a lack of common language and tools.

So it’s no wonder that if you ask any roomful of leaders or potential leaders what effective leaders need to be, know, or do, you get as many answers as there are people in the room. Leaders are authentic, have judgment, emotional intelligence, practice the Seven Habits (Covey), and know the 21 Irrefutable Laws (Maxwell). They are like Lincoln, Moses, Jack Welch, Santa Claus, Mother Teresa, Jesus, Mohammed, and Attila the Hun. So with all of the information, what does it really mean to be an effective leader and why are we writing yet another chapter on the topic?

We believe it is time to bring together decades of theorizing about leadership: we need to simplify and synthesize rather than generate more complexity and confusion. Faced with the incredible volume of information about leadership, we (along with our colleague and coauthor Kate Sweetman) turned to recognized experts in the field who had already spent years sifting through the evidence and developing their own theories. These “thought leaders” had each published a theory of leadership based on a long history of empirical research on what makes effective leadership. Collectively, they have written over 50 books on leadership and performed well over 2,000,000 leadership 360 feedback assessments.1

In our discussions with them, we focused on two simple but elusive questions:

1. What percent of effective leadership is basically the same? Are there some common rules that any leader anywhere must master? Is there a recognizable Leadership Code?

2. If there are common rules that all leaders must master, what are they?

To the first question, the experts varied as they estimated that somewhere in the range of 50 to 85 percent of leadership characteristics were shared across all effective leaders. The range is fairly broad, to be sure, but consistent. As one of our interviewees put it: “I think… that 85 percent of the competencies in various competency models appear to be the same. I think we have a relatively good handle on the necessary competencies for a leader to possess in order to be effective.” Then the expert added something of equally great significance: “But there are some other variables that competency models do not account for. [These] include… the leader’s personal situation (family pressures, economics, competition, social, etc.); internal influences, such as health, energy, vitality, resilience; the intensity of effort the individual is willing to put forth; ambition and drive, willingness to sacrifice.”

THE LEADERSHIP CODE

From the body of interviews we conducted, we concluded that 60 to 70 percent of leadership effectiveness would be revealed in a code—if we could crack it! Synthesizing the data, the interviews, and our own research and experience, a framework emerged that we simply call the Leadership Code.

An analogy guided our thinking. How different is a luxury Lexus sedan from a Chrysler minivan? If you are like most people, you likely view the two vehicles as being very different from each other, perhaps even opposites. The Lexus appeals to people interested in comfort and prestige, while the minivan is a perfect vehicle for an active family on a budget. You may love to drive either one and not want to be caught dead in the other, believing them to be very different species.

But are they really? Underneath the obvious external characteristics, they share more in common than they differ. First of all, they are both forms of individual (versus mass) transportation. They both get you where you need to go. They each do that by sharing an important set of core elements: drive train, crankshaft, brakes, wipers, blades, and batteries. In fact, when you add it up, the degree to which any two cars share fundamental similarities is much greater than their differences.

As we listened to leadership experts, we felt that the same logic would apply. Does an effective leader at Wal-Mart in any way resemble an effective leader at Virgin Airlines? Does an effective leader in a bootstrapping non-governmental organization in any way resemble one at the famously bureaucratic United Nations? Does an effective leader in an emerging market resemble one in a mature market? Does an effective leader in organized crime in any way resemble one in organized religion? Does an effective leader in a Swiss pharmaceutical company share any underlying characteristics with an effective leader at Google?

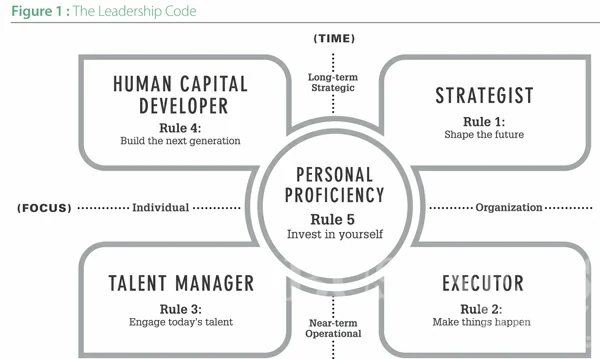

In an effort to create a useful visual, we have mapped out two dimensions (Time and Focus) and placed what we are calling Personal Proficiency (self-management) at the center as an underlying support for the other two. Figure 1 synthesizes the Leadership Code and captures the five rules of leadership that make up leadership DNA.

Rule 1: Shape the Future. This rule is embodied in the Strategist dimension of the leader. Strategists answer the question, “Where are we going?” and make sure that those around them understand the direction as well.

They figure out where the organization needs to go to succeed; they test these ideas pragmatically against current resources (money, people, organizational capabilities); and they work with others to figure out how to get from the present to the desired future. Strategists have a vision about the future and are able to position their organization to create and respond to that future. The rules for Strategists are about creating, defining, and delivering principles of what can be.

Rule 2: Make Things Happen. Turn what you know into what you do. The Executor dimension of the leader focuses on the question, “How will we make sure we get to where we are going?” Executors translate strategy into action and put the systems in place for others to do the same. Executors understand how to make change happen, assign accountability, know which key decisions to take and which to delegate, and make sure that teams work well together. They keep promises to multiple stakeholders. The rules for Executors revolve around discipline for getting things done and the technical expertise to get the right things done right.

Rule 3: Engage Today’s Talent. Leaders who optimize talent answer the question, “Who goes with us on our business journey?” Talent Managers know how to identify, build, and engage talent to get the needed results now. They identify what skills are required, draw talent to their organizations, engage them, communicate extensively, and ensure that employees turn in their best efforts. Talent Managers generate intense personal, professional, and organizational loyalty. The rules for Talent Managers center around resolutions that help people develop themselves for the good of the organization.

Rule 4: Build the Next Generation. Leaders who are Human Capital Developers answer the question, “Who stays and sustains the organization for the next generation?” Talent Managers ensure shorter-term results through people, while Human Capital Developers ensure that the organization has the longer-term competencies required for future strategic success; they ensure that the organization will outlive any single individual. Just as good parents invest in helping their children succeed, Human Capital Developers help future leaders be successful. Throughout the organization, they build a workforce plan focused on future talent, understand how to develop that talent, and help employees see their future careers within the company. Human Capital Developers install rules that demonstrate a pledge to building the next generation of talent.

Rule 5: Invest in Yourself. At the heart of the Leadership Code—literally and figuratively—is Personal Proficiency. Effective leaders cannot be reduced to what they know or what they do. Who they are as human beings has everything to do with how much they can accomplish with and through other people. Leaders are learners: from success, failure, assignments, books, classes, people, and life itself. Passionate about their beliefs and interests, they expend an enormous personal energy and attention on whatever matters to them. Effective leaders inspire loyalty and goodwill in others because they themselves act with integrity and trust. Decisive and impassioned, they are capable of bold and courageous moves. Confident in their ability to deal with situations as they arise, they can tolerate ambiguity.

Over the last few years that we have worked with these five rules of leadership, we have come to some summary observations:

n All leaders must excel at Personal Proficiency. Without the foundation of trust and credibility, you cannot ask others to follow you. While individuals may have different styles (introvert/extrovert, intuitive/sensing, etc.), any individual leader must be seen as having Personal Proficiency to engage followers. This is probably the toughest of the five domains to train and some individuals are naturally more capable than others.

n All leaders must have one towering strength. Most successful leaders have at least one of the other four roles in which they excel. Most are personally predisposed to one of the four areas. These are the signature strengths of your leaders.

n All leaders must be at least average in his or her “weaker” leadership domains. It is possible to train someone to learn how to be strategic, execute, manage talent, and develop future talent. There are behaviors and skills in each domain that can be identified, developed, and mastered.

n The higher up the organization that the leader rises, the more he or she needs to develop excellence in more than one of the four domains.

WHAT ELSE IS NEEDED? LEADERSHIP BRAND

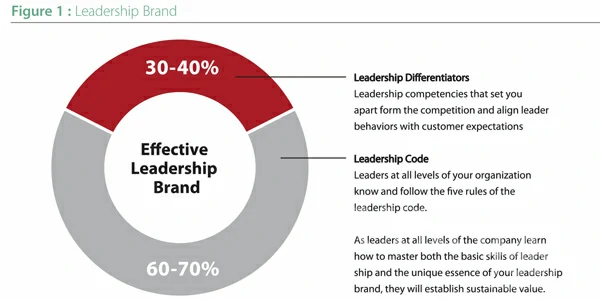

We describe the Leadership Code as a synthesis of what it takes to be an effective leader. According to our thought leaders, it also explains about 60 to 70 percent of the leadership puzzle. So, what’s the other 30 to 40 percent?

Think of giving Richard Branson, Chairman of the Virgin Group, and Jeff Immeldt, CEO of General Electric (GE), a Leadership Code 360. We bet that both would score very high! Both are strong strategists; they both know how to execute and to get their ideas implemented by others; they are both high in Personal Proficiency; both are Talent Developers; and both are concerned about the next generation of talent and act as Human Capital Developers. So, according to our 360, they are both effective leaders. They have the core Code competencies. But they are also very different.

From a personal style perspective, Immeldt tends to be more corporate looking than Branson. He wears his hair shorter, is clean shaven, and most of the time wears a suit and tie; we’re not sure if we’ve ever seen the shaggy haired Branson in a suit much less a tie. Branson is playful, while Immeldt tends to come across as more conservative and businesslike. Immeldt speaks in a more articulate manner and Branson tends to use “colorful” language to make his points. Branson seems more fun loving while Immeldt seems more authoritative. So, they have some differences in their style and perhaps some important other differences as leaders. And, the Leadership Code 360 does not pick up what we call “leader differentiators.” So what are leader differentiators and how are they different from the fundamentals of the Leadership Code?

In our book, Leadership Brand: Developing Customer-Focused Leaders to Drive Performance and Build Lasting Value (Harvard Business School Press, 2007), we focused on these unique aspects of leadership and derived a simple formula:

Rather than derive leadership differentiators from interviews of successful and less-successful leaders (a traditional approach in most competency models), we suggest that leadership differentiators for any organization may be derived from the firm’s identity or firm brand. This firm brand is the way the company wants to be described by its target customers. Typically, the firm brand descriptors are the firm’s customer value proposition along with how the company wants its target customers to experience that value proposition. Southwest Airlines’ value proposition is “low price.” However, Southwest also wants its customer to experience the low-price value proposition in a different way than other low-price airline competitors—it wants Southwest customers to see it also as “on time” and “fun.” These three words—Low Price, On-Time, and Fun—are Southwest’s firm brand identity in the minds of their best customers. Defining leadership from the outside in, by starting with customer expectations, ensures that leadership behavior inside a firm drives the customer experience.

…Develop Leaders At Every Level Who Have Their Own Style That Fits Within The Context Of The Differing Firm Identities, The Company Has A Leadership Brand That Is Appreciated By Customers And Employees And Rewarded By Financial Markets As An Envied Capability.

The next step is to translate these firm brand descriptors into unique leadership differentiators, i.e., the unique leadership competencies that make the firm brand real to the customer whenever they interact with any employee of the firm. These leadership differentiators are always outside in; they bring the customer mindset to the table. In the Southwest Airlines example, the best firm leaders make sure that whenever a customer flies on a Southwest flight, they have a fun experience. Founder Herb Kelleher (perhaps one of the few leaders on the planet who makes Richard Branson look conservative) personifies “fun” at Southwest. It’s easy to find pictures of Herb in drag, in a tutu, or celebrating key milestones for his company in other outrageous (think fun) ways. On down through the ranks, Southwest selects “fun” leaders, rewarding people in any job who improvise to find ways to have fun with customers in a way the customer enjoys, and celebrating their successes. As a result of the culture that is reinforced by leaders at every level, most customers find flying on Southwest to be a unique experience that they quite enjoy—even if they do not get a first-class seat or a free meal.

Let’s revisit Immeldt and Branson now. Jeff Immeldt personifies GE’s firm identity. He is a role model to other GE leaders about how the firm should be seen by outside stakeholders. GE’s firm identity is about organic growth and innovation with a lot of measurement and accountability going on. Virgin’s firm identity is about fun, irreverence, and challenging the status quo, and that’s exactly what Richard Branson is constantly doing. He lives on an island and seems to enjoy the high life in ways that the rest of us can only dream of. He personifies the leadership style of the Virgin brand.

When GE or Virgin or Southwest can develop leaders at every level who have their own style that fits within the context of the differing firm identities, the company has a leadership brand that is appreciated by customers and employees and rewarded by financial markets as an envied capability.

At a personal level, you are your own brand. You need to define and become the leader you want to become. You need to create personal differentiators that distinguish you from others. By mastering the code and developing differentiators, you establish your identity and personal brand and can align it to create or complement your organization’s leadership brand.

It’s not about Leadership Code versus Leadership Differentiators. It’s about building leaders who have both. Leaders need to have the Leadership Code building blocks to be effective and they need to know their organization’s unique brand in terms of how it delivers on the desired customer connection. Effective leaders know and do the fundamentals of both the Leadership Code and Leadership Differentiators. It’s not easy to be an effective leader, but getting clarity amidst all of the confusing signals about what it entails is a good start.

1These generous thought leaders included: Jim Bolt (working on leadership development efforts); Richard Boyatzis (working on the competency models and resonant leadership); Jay Conger (working on leadership skills as aligned to strategy); Bob Fulmer (working on leadership skills); Bob Eichinger (working with Mike Lombardo to extend work from Center from Creative Leadership and leadership abilities); Marc Effron (working on large studies of global leaders); Marshall Goldsmith (working on global leadership skills and how to develop those skills); Gary Hamel (working on leadership as it relates to strategy); Linda Hill (working on how managers become leaders, and leadership in emerging economies); Jon Katzenbach (working on leaders from within the organization); Jim Kouzes (working on how leaders build credibility); Morgan McCall (representing Center for Creative Leadership); Barry Posner (working on how leaders build credibility); Jack Zenger and Joe Folkman (working on how leaders deliver results and become extraordinary).