The subject of directors and executive remuneration is of substantial practical importance for shareholders and policymakers in the developed world and ignored by the developing world. The main objective of this analysis is to provide a full account of how power and influence can shape the directors’ remuneration landscape. The analysis will also contribute to a better understanding of the flaws in corporate governance process contributing to the current compensation arrangements. Such an understanding may help the regulator to address these problems.

“The world of CEOs and boards has become an entitled insiders’ club-virtually free of accountability-and the abject failure of our corporate leaders to police themselves is costing Americans trillions and seriously undermining the strength of our economy. Whereas boards are supposed to act as watch-dogs, guarding shareholders’ interests, they have become enabling lapdogs to CEOs, who are aided and abetted in their pursuit of outrageous pay and unfettered power by a bevy of supporting players, including compen-sation consultants who justify exorbitant pay packages and accountants and attorneys who see no evil.”

The above is from the book ‘Money for Nothing: How the Failure of Corporate Boards is Ruining American Business and Costing US Trillions’ an exposé of how the game is played and a powerful call for change to fix the glaring dysfunctions that are imperiling the health of American business. It is based on extensive original reporting and interviews with high-level insiders at a host of leading companies, John Gillespie and David Zweig-both Harvard MBAs with thirty plus years of Fortune 100 experience-reveal the inner workings of this dysfunctional culture and the many methods CEOs and boards use to shut shareholders out, entrench themselves, and fight reforms with shareholders’ own money.

Since The Global Financial Crisis, Executive Compensation Has Been In The Spotlight And Will Continue To Be A Hot Topic For Directors In 2017 Due To Active Rule Making By The US SEC, For American Corporates.

The New York Times praised the book saying: “The authors offer a valuable new perspective by focusing on the tragicomic miscues of the people who were ostensibly meant to ‘govern’ out-of-control manage-ments…”

Background

Since the global financial crisis, executive compensation has been in the spotlight and will continue to be a hot topic for directors in 2017 due to active rule making by the US SEC, for American corporates. While considering the backdrop for such events let’s see if our country can learn something or gain insights from these developments.

The collapse of many powerful corporates mainly in the US is blamed on ‘greed’ of cor-porate America. It’s a feature not definitely limited to America but followed in every country in the world, and more rampant in the under developed countries. The compensation and incentives of boards and senior executives were not linked to long-term interest of the company. This behaviour led to regulators insisting on board committees having to take more respon-sibilities in evaluating remuneration-related proposals by management.

One of the cases cited by most people sup-porting control over director compensation is related to Stanley O’Neal the Chairman and CEO of Merrill Lynch. The board paid O’Neal USD 48mn in salary and bonus for 2006 – probably the highest compensation in America. Just 10 months later he had to make a USD 8.3bn write down on failed investments and made the biggest loss in their 93 year history. He was ousted by the board later with an exit package worth USD 161.5 mn. Not a bad deal for driving the collapse of a reputed company?

In 2012, the US Securities and Exchange Commission included the Dodd Frank Act to its rules, with a number of provisions generally relating to the independence of compensation committees and their advisers. DFA required compensation advisers with proper knowledge and experience to counter the boards’ lack of it. The key changes were; to prohibit the listing of any security of an equity issuer that does not comply with listing rules regarding:

– compensation committee member independence,

– a compensation committee’s authority to engage compensation advisers, and

– a compensation committee’s consideration of certain relevant factors in selecting a compensation adviser.

Further, the OECD code (Principle VI.D.4) also endeavoured to strengthen compensation practices and identified the following as a key function of the board:

“Aligning key executive and board remuneration with the longer term interests of the company and its shareholders.”

It is generally accepted that fraud and corruption in many circumstances are part of a culture that’s only focused on performance at any cost. If remuneration policies also support such behaviour, then the boards who set such tone at the top should be held responsible. Therefore, it is important to develop and disclose a remuneration policy statement covering board members and key executives. Such a policy should specify the relationship between remuneration and performance, and include measurable standards that emphasise the longer term interests of the company. Rewarding short term interests and excessive risk taking should not be encouraged by such policies.

“Aligning Key Executive And Board Remuneration With The Longer Term Interests Of The Company And Its Shareholers.”

One of the projects of OECD after the financial crisis identified the following key findings and main messages with regard to governance of the remuneration process;

– The governance of remuneration/incentive systems has often failed because negotiations and decisions are not carried out at arm’s length. Managers and others have had too much influence over the level and conditions for performance based remuneration with boards unable or incapable of exercising objective, independent judgment.

– In many cases it is striking how the link between performance and remuneration is very weak or difficult to establish. The use of company stock price as a single measure for example, does not allow to benchmark firm specific performance against an industry or market average.

– Remuneration schemes are often overly complicated or obscure in ways that camou-flage conditions and consequences. They also tend to be asymmetric with limited downside risk thereby encouraging excessive risk taking.

– Transparency needs to be improved beyond disclosure. Corporations should be able to explain the main characteristics of their performance related remuneration progra-mmes in concise and non-technical terms. This should include the total cost of the programme; performance criteria and; how the remuneration is adjusted for related risks.

– The goal needs to be remuneration/incentive systems that encourage long-term performance and this will require instruments to reward executives once the performance has been realised (i.e. ex-post accountability).

– Defining the structure of remuneration/incentive schemes is a key aspect of corporate governance and companies need flexibility to adjust systems to their own circumstances. Such schemes are complex and the use of legal limits such as caps should be limited to specific and temporary circumstances.

– Steps must be taken to ensure that remuneration is established through an explicit governance process where the roles and responsibilities of those involved, including consultants, and risk managers, are clearly defined and separated. It should be considered good practice to give a significant role to non-executive independent board members in the process.

– In order to increase awareness and attention, it should be considered good practice that remuneration policies are submitted to the annual meeting and as appropriate subject to shareholder approval.

– Financial institutions are advised to follow the Principles for Sound Compensation Practices issued by the Financial Stability Forum that can be seen as further elaboration of the OECD principles.

Source: OECD Key Findings

In Sri Lanka, due to limited public information it’s not clear if the post Enron reforms initiated by the Stock Exchange and SEC calling for more independent directors and controlling related party transactions have done enough to prevent governance disasters. The negative result which is generally heard is that boards are now spending more time on ‘ticking the boxes’ and legally resorting to “cover your ass” (CYA as popularly known) approach rather than allocating more time to formulating strategy, identifying & mitigating risks, succession planning or performance evaluations. Therefore resulting in more time being spent in the Board as compared to pre 2000 era, thereby driving director compensation to higher levels. We will not see the depth of any such problems until there is a crisis and it may be too late, like the world saw it in 2008.

John Gillespie and David Zweig summed up the feeling by writing “The world of boards has become an entrenched insiders’ club-virtually free of accountability or personal liability”. Board members get too much for too little work, they concluded.

Compensation

Compensation packages comprise of many different components. For non-executive directors (NEDs) most companies in Sri Lanka have a monthly retainer and fees for additional responsibilities taken through committee level participation. In addition, some others may pay a meeting fees for participation at meetings. It is unlikely that share options are given to NEDs. Executive directors will be offered share options and many other non-cash perquisites in addition to their salary and bonus.

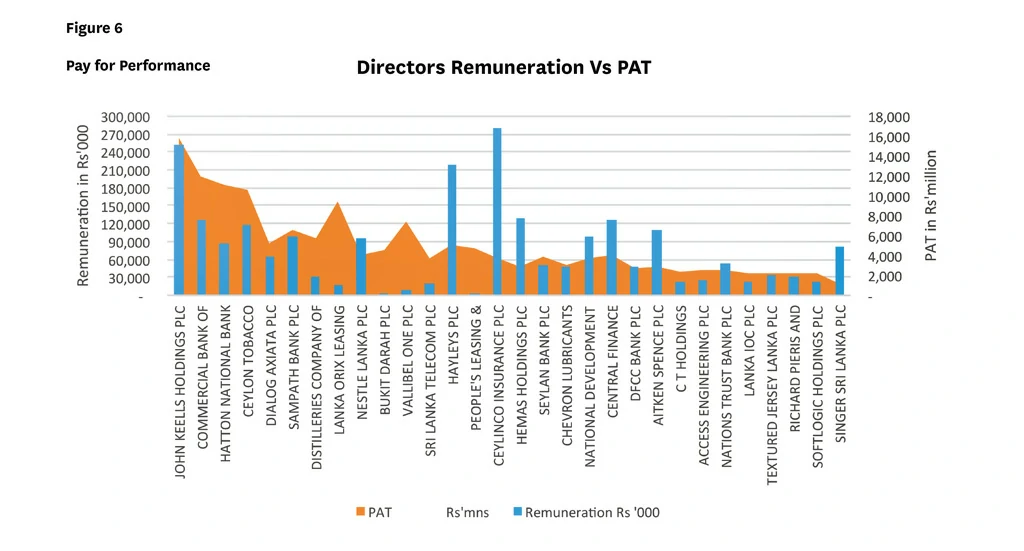

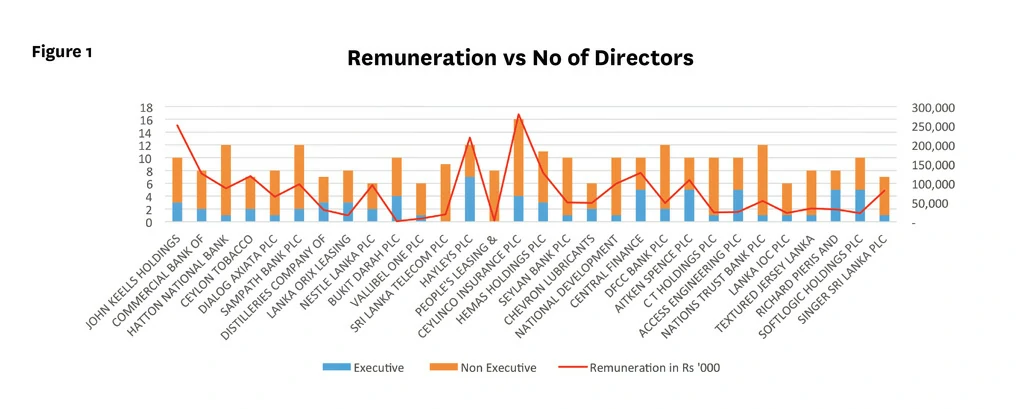

A comparison of remuneration paid to directors and the composition of executive and NEDs among the Business Today TOP 30 companies in 2015/2016, shows no correlation between the numbers of directors, their composition and the quantum of remunerations paid. The 3 companies which pay directors in excess of Rs 200mn a year have 3, 7 and 4 executive directors and 7, 5 and 12 NEDs respectively. On the contrary, another 3 companies in the TOP 30 list pay less than 10mn a year to all their directors. This may beg the question if compensation is commensurate to the minimal services expected of directors. To be a little more insightful let us resort to comparing the compensation to profits made by these companies, later in this analysis (figure 5).

A warning about this analysis is that the amounts disclosed were extracted from the annual reports published by these companies and the disclosure errors and lack of clarity noted in at least 10 companies (out of the Business Today TOP 30) was concerning. In some cases it is not clear if the companies understand the difference between fees, remuneration, salaries and expenses.

In one of the companies, it is not clear if the CEO’s compensation was included in the legally required disclosure under the Companies Act although he is also a director. Further, there was no clarity on any non-cash perks being included in the disclosure.

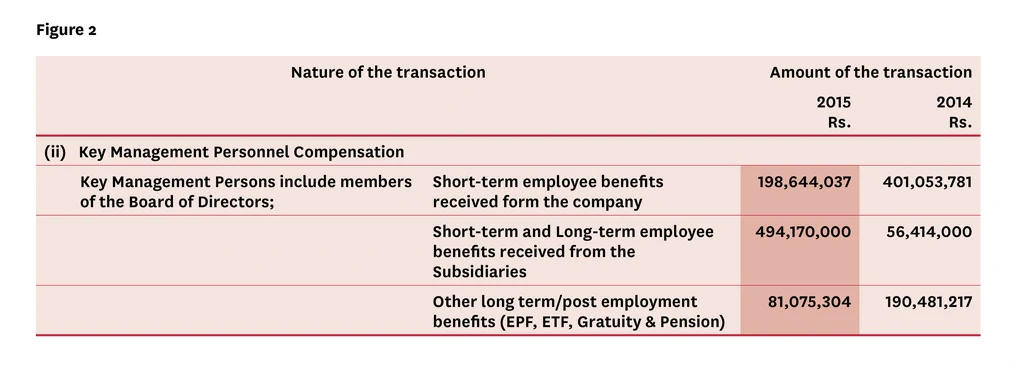

Another major amount not included in the above analysis relates to a disclosure by an insurance company that has disclosed benefits received from subsidiaries by the directors of Rs 494.17mn as reflected in Figure 2. As it is unclear if the key management personnel were the same as the directors of the holding company and if they were paid for services rendered to the subsidiaries or to the holding, this amount was excluded from the analysis. If not for the exclusion, the remuneration component would have been literally ‘off the chart.’

There is a global trend to align director’s interest with shareholder interests. Up to now shareholders have not dwelt much on whether directors should be paid for performance. Instead, they have primarily recommended paying NEDs a standard retainer and have a compensation plan for executive directors, which does not really encourage anything other than a ticking the box compliance based behaviour.

Independence

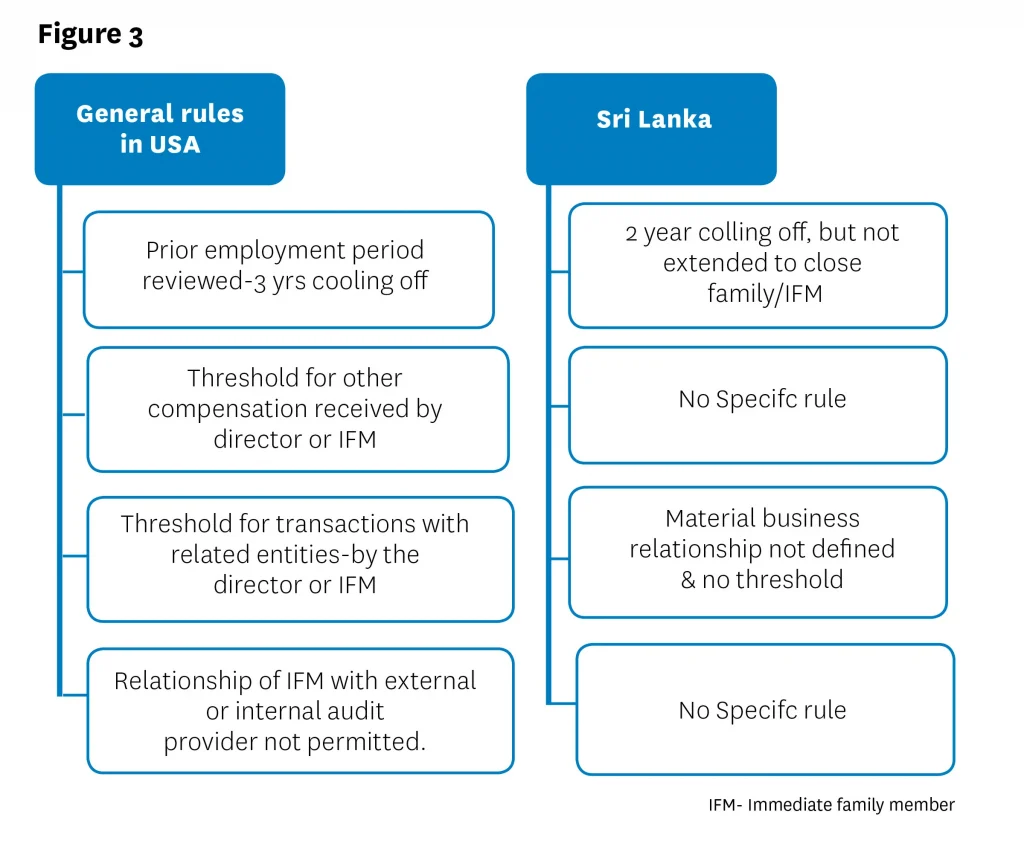

Independence is the other important aspect of directors that contributes to better governance. This helps them to be objective and free of conflicts of interests. Directors are expected to carry out their responsibilities on an arm’s length basis without impinging fiduciary, governance and oversight requirements inherent in their roles. Sarbanes-Oxley and Dodd-Frank Acts in the US, outline the importance of board directors being independent of the organization. The NYSE and NASDAQ exchanges set thresholds for independence tests in order to meet a high standard. The comparison in figure 3, shows how the local independent directors will fail the test for Independence:

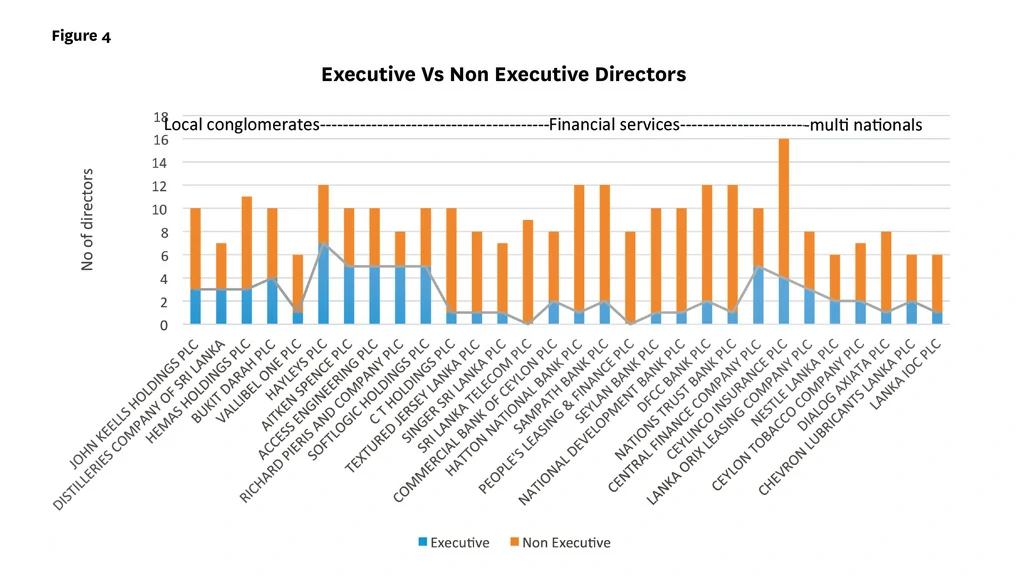

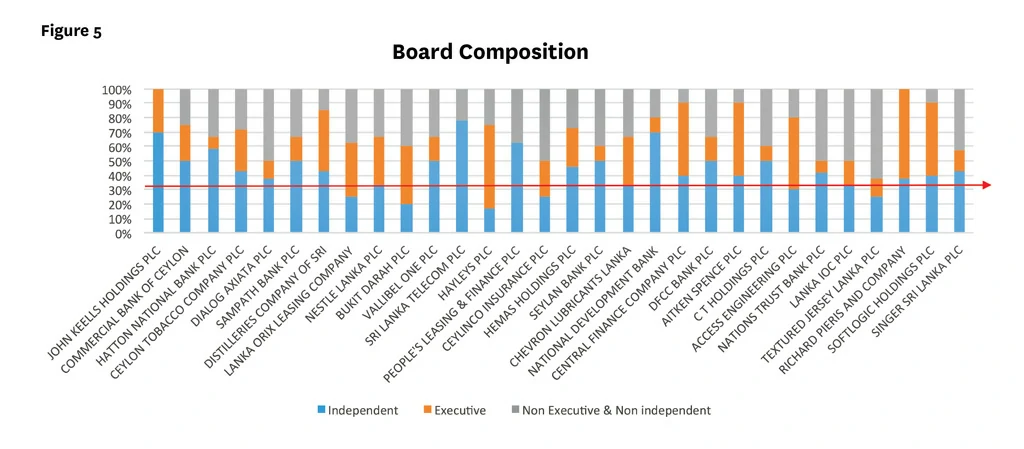

Sri Lanka should strengthen rules to nominate independent directors (IDs) and the composition. As reported in the Corporate Governance Assessment on the Business Today TOP 30, 2015/16, Independence cannot be codified through statute or rules, but rules are like the traffic lights on the roads that keep discipline. Further, the composition should encourage at least 1/3rd of the board should comprise independent directors (not limit to 1/3rd of NEDs) and in case of an executive chairman, at least half of the board should be independent. An analysis of the com-position of executive directors and NEDs in the Top 30 companies is depicted in figure 4:

It can be observed that the separation line favours executive directors in many local conglomerates and little less in multi-national corporates operating in Sri Lanka. However in banks, due to regulations NEDs are the majority, providing confidence to the public of the ability to be independent and objective in their decision making. Due to the lack of monitoring in Sri Lanka, such composition does not achieve the intent that a board director should have no material relationship with the organisation directly or indirectly that may lead to a conflict of interest or undue influence. The relationships in the purview of the independence standard should identify commercial, banking, consulting, accounting, auditing, legal, charitable, financial, and/or familial relationships rather than a mere shareholding based analysis.

Composition

To improve independence and time commitment to the task there should be limits to the number of companies that a person may be elected as an ID. This may vary depending on whether a person is a full time ID or practicing a profession or in employment or business. Further, the term of office for an ID also should be limited, for example 9 years in the financial services sector. Where a person is an independent director of a business conglo-merate (parent company, subsidiary, associate and any affiliate), he should be elected as an ID to a limited number of companies of such conglomerate/group. Figure 5 highlights companies, which do not have 1/3rd independent directors on their boards. The nomination committee should be mandated to evaluate director performance prior to recommending them for reappointment. Ideally, keeping directors who ask relevant and challenging questions. Management guru Peter Drucker is quoted to have said “The most serious mistakes are not being made as a result of wrong answers. The truly dangerous thing is asking the wrong question.”

The inequity between profits and compensation in the TOP 30 companies is not unusual, despite the camouflaging of benefits to directors and errors in disclosure mentioned earlier in the analysis. In the book published in 2004 by Harvard University Press, ‘Pay without Performance – The Unfulfilled Promise of Executive Compensation’ by Lucian Bebchuk and Jesse Fried, it was stated: “Firms have systematically taken steps that make less transparent both the total amount of compensation and the extent to which it is decoupled from managers’ own performance. Managers’ interest in reduced transparency has been served by the design of numerous compensation practices, such as post retirement perks and consulting arrangements, deferred compensation, pension plans, and executive loans. Overall, the camouflage motive turns out to be quite useful in explaining many otherwise puzzling features of the executive compensation landscape.”

The Future

Due to the USSEC’s active rulemaking in 2015, directors will have more to worry about than just compensation. Roughly five years after the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act was enacted, the USSEC finally adopted the much anticipated CEO pay ratio disclosure rules, which have already begun stirring the debate on income inequality and exorbitant CEO pay, at least in the US. The USSEC also made headway on other Dodd-Frank regulations, including rules requiring:

– Advisory votes of shareholders about executive compensation and golden parachutes.

– Disclosure about the role of, and potential conflicts involving, compensation consultants. This statute also requires the Commission to direct that the exchanges adopt listing standards that include certain enhanced independence requirements for members of issuers’ compensation committees.

– Additional disclosure about certain compensation matters, including pay-for-performance and the ratio between the CEO’s total compensation and the median total compensation for all other company employees.

– The Commission to direct the exchanges to prohibit the listing of securities of issuers that have not developed and implemented compensation claw-back policies.

– Additional disclosure about whether directors and employees are permitted to hedge any decrease in market value of the company’s stock.

“Firms Have Systematically Taken Steps That Make Less Transparent Both The Total Amount Of Compensation And The Extent To Which It Is Decoupled From Managers’ Own Performance.”

Similar to the US, in the UK too it was claimed that pay structures (particularly bonuses) had contributed to a culture of excessive risk-taking among Britain’s banks, thereby helping to precipitate a major economic crisis. The UK took the initiative to address the deteriorating situation and to improve corporate governance and reform remuneration practices, like;

– The publication of the Remuneration Code of the Financial Services Authority (FSA), requires the largest financial institutions of the United Kingdom to ‘establish, implement and maintain policies, procedures and practices that are consistent with and promote effective risk management’.

– The Walker Report on the corporate governance of the financial services sector; Some of the Walker rules on pay, include;

– The remuneration committee should be directly responsible for the pay of not just directors but also of those regarded by the FSA as having a ‘significant influence function’ or who may have ‘a material impact on the risk profile of the entity’, giving the committee a greater control over a company’s pay pra-ctices.

– The remuneration committee should have oversight of remuneration policy throughout the business, though it will only set pay packages for the most senior staff.

– The remuneration committee should confirm, in its report, that it is satisfied with the way performance objectives and risk adjustments are reflected in compensation structures for senior management.

– It must also report whether it has the power to enhance an executive’s benefits in certain circumstances such as termination of employ-ment or a change of control.

– A revised UK Corporate Governance Code from the Financial Reporting Council; Some of the changes focus on aligning reward with the sustained creation of value, including;

– Greater emphasis to be placed on ensuring that remuneration policies are designed with the long-term success of the company in mind, and that the lead responsibility for doing so rests with the remuneration committee; and

– Companies should put in place arrangements that will enable them to recover or withhold variable pay when appropriate to do so, and should consider appropriate vesting and holding periods for deferred remuneration.

As the USSEC, UK FRC and some other key regulators around the globe are focusing on improving governance over CEO and director compensation, we hope that Sri Lanka will follow suit to strengthen the existing weak independence rules for boards and also ensure director/CEO compensation is not excessive and not made at the expense of creating shareholder value.

Suren Rajakarier FCA, FCCA, FCMA (UK), CGMA and contributor to the annual BUSINESS TODAY’s TOP 30 Corporate governance assessment.