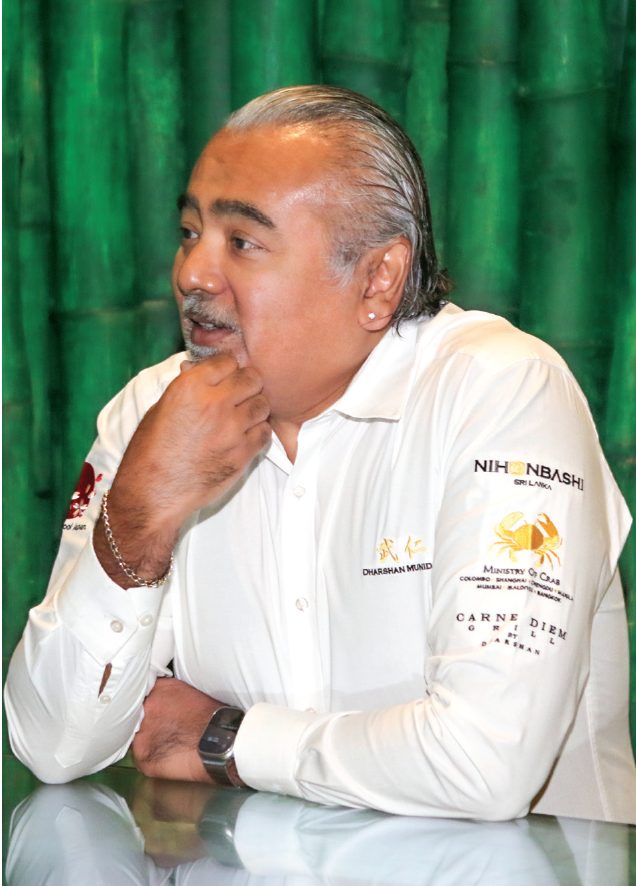

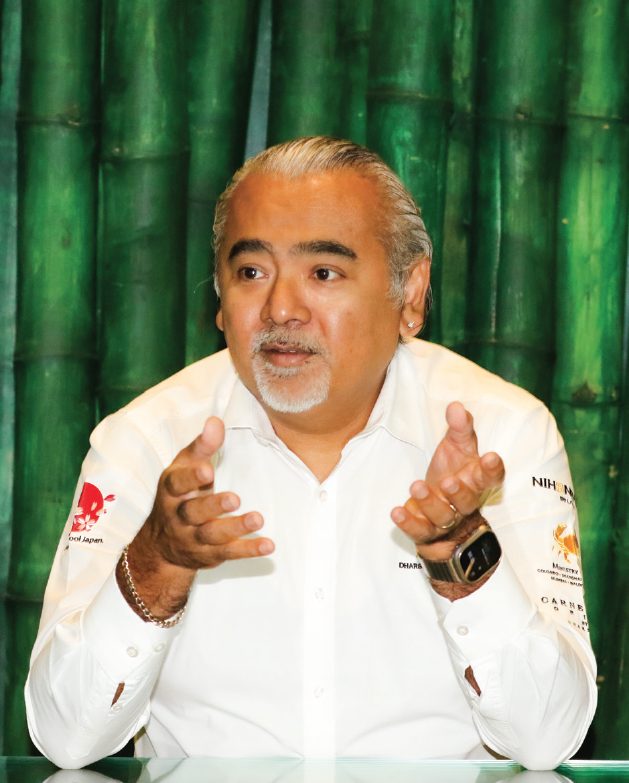

Dharshan Munidasa, Founder, Nihonbashi.

Nihonbashi started as a family-run restaurant in 1995, with Dharshan Munidasa and his mother at its helm. For its first five years, its patrons were solely Japanese. Nihonbashi at Galle Face Terrace came to light only when they opened an outlet at Odel, which saw Sri Lankans flocking to get a taste of authentic Japanese food. Today, we can describe Dharshan’s business as his unique food empire. He has carved a niche for himself meticulously, a taste and reputation carved with such dedication and precision that anyone else trying to imitate him in Sri Lanka has failed.

Dharshan has made many headlines around the world. Nihonbashi and Ministry of Crab are the only two restaurants in Sri Lanka ranked on Asia’s 50 Best Restaurants List. He made headlines again by becoming the first restaurateur to open at the Colombo Port City. Speaking to Business Today, Dharshan, whose rise to food stardom has been well-documented globally, explained his latest move to Port City. He has demonstrated that his restaurants are more than just food. He has created a culture and a team that follows his philosophy of order and structure and a deep respect for how food is prepared and served. While precision and attention to detail are at the heart of his success, passion and depth are the secret to their longevity.

Words Jennifer Paldano Goonewardane.

Photography Sujith Heenatigala and Dinesh Fernando.

From Galle Face Terrace to the Port City. Why now?

Nihonbashi opened as a small family-run restaurant in 1995 when Sri Lanka was still waging an internal war. It filled a vacuum for authentic and traditional Japanese food, which was embraced wholeheartedly by the Japanese community living in Sri Lanka then. The community then would have been around two thousand. Nihonbashi grew spurred by my curiosity and eagerness to learn. I’d learn from a fishmonger. I began looking for ingredients in Sri Lanka. In Sri Lanka, we live within twenty-five minutes of a fishing village. So we interact with ingredients, unlike in other countries that receive everything in a box where the restaurant has no connection with the individuals who caught the fish or harvested the spices.

Over the years, Nihonbashi has been changing and evolving. Following a spate of recent events, beginning with the 2019 bombings, COVID-19, the economic crisis, and the disruptions, Nihonbashi needed a massive revamp. To do that at Galle Face Terrace would have been an enormous task. So, while we were looking to write the next chapter of Nihonbashi, the Port City came to us. It is a great opportunity and a great location. I have taken the restaurant business to a new level by using local ingredients and sourcing local materials to build this restaurant. I expanded the repertoire of a chef from a plate to much more. The table the plate rests on, the floor the table rests on, and the rooms we’ve created have a story; for us, it has been twenty-nine years of storytelling. What you see has evolved in the last twenty-nine years: a combination of Sri Lankan ingredients and Japanese cooking.

How have you changed Sri Lanka’s food landscape and its culinary reputation?

After opening Nihonbashi at Galle Face Terrace as our first restaurant, we expanded, opening one at Odel. At just four hundred square feet, it was the smallest Nihonbashi. However, that restaurant made Japanese food famous in Sri Lanka. Then we also set up at Colombo Hilton Residence. We were the only Japanese restaurant with three outlets in the city when everyone else had one. Despite the instability in the country, the suicide bombings, curfews, power outages, and strikes, we grew, and our business became strong. I grew as well. I sourced my ingredients directly by going to Pettah, interacting with merchants, and building relationships with them over time.

Many of my friends were astonished that someone of my education was interacting with traders and fishmongers in Pettah and other places and that I would get my hands dirty choosing the ingredients because, in practice, a business owner would never interact directly with suppliers. They always had people procuring the ingredients for them. But we changed that, and now many, after me, have started visiting those places to procure their ingredients directly. The good thing about interacting with the merchants and suppliers is that you convey your desired standards and quality, and they fall in line. The fisherman knows the quality of the tuna and the crab I serve in my restaurants. He knows how to preserve it after harvesting it the best way I want. Intermediaries cannot guarantee the standards that I am looking for.

The table the plate rests on, the floor the table rests, and the room we create has a story; for us, it has been twenty-nine years of storytelling.

Sri Lanka was only known for tea, cinnamon, gems, and Buddhism. We were never known for our food. Sri Lankans themselves define their food as just rice and curry. But it is beyond that. It’s not rice and curry; it is curry and rice. There is more variety and depth in what we do. I took a single ingredient and made a restaurant out of it. So that’s the Japanese side of contributing towards Sri Lanka’s food landscape and reputation. Ministry of Crab is a Sri Lankan mud crab restaurant. Apart from three or four dishes, our flavors are different from Sri Lankan. But we shone because we used a fresh Sri Lankan ingredient and said no to freezers. How many other countries can do that? As we plan to open an MOC in Singapore, we are trying to practice our no-freezer policy there, and if we succeed, it will be the first restaurant in Singapore to achieve it. Being an engineer, I can push the limits. My mixed heritage and growing up surrounded by the ocean has allowed me to experiment.

If we take the local food landscape, what can we do better?

Stop using MSG. Street food in Asia uses tons of MSG. None of my restaurants use it, nor can I eat food containing MSG. We are a country with enormous natural resources to make flavors naturally. We balance flavors, textures, and colors, which come with talent and mindfulness when we treat ingredients respectfully. It is more than simply running a restaurant that serves a menu. There is so much we can do to create a unique identity for our food.

With a few changes, we can make serving Sri Lankan food interesting. We can package the elementary packet or box of rice uniquely. Why can’t we make a difference by naming the fish or the rice served? We could give an identity to the rice, as rice harvested in Polonnaruwa or Anuradhapura in the Maha season. We have immense choices in how we offer our food. It’s all about paying attention to detail, and that makes a world of difference. We can do the same with Ceylon Tea, moving to something more from the typical tea served with and without milk. We have abundant local ingredients to offer a variety of choices, but first, we must respect the ingredients. They can’t be just part of everyday preparations. We must educate people on their importance and show how best to use them to serve a consistent dish. We have fresh products from the ocean, but we don’t bother to go deeper to create a bigger story for them. We must add value to that privilege.

What is the work culture in your restaurants since you represent two distinctly different cultures, Japanese and Sri Lankan?

I think my staff knows that we aren’t a democracy. It’s close to a dictatorship, especially in the kitchen. I can’t have second opinions about something we decided once. In our business, it’s all about execution and teamwork. I can best describe how we work through the role of a sports captain whose leadership has to shine through intense situations when they have to make quick decisions according to the realities on the ground, such as reacting to the different outcomes on the field and responding appropriately when the ball changes direction. Under such scenarios, the team leader or the teammates have no time to stop and take a vote on how they should respond. They have trained the team to respond accordingly. There is nothing dictatorial or undemocratic about such a setup. It is a must to win the game. Likewise, our business’s ground realities also change every minute and every day. Things may even change mid-sentence. I have to rely on a big team where each acts independently without expecting someone else to respond to a situation, and that’s how we get results. So, as a boss, I am very strong-minded, and I make sure my team knows that.

As I said, teamwork is critical to our success, and I have ingrained this in my teams across our restaurants. Creating Nihonbashi at the Port City was one such effort. I told my staff that I was building something I didn’t know. It does not exist anywhere, and I’m not copying something I have seen in another country. We will make mistakes, but I will need your hands on deck when the time comes. So, when we were putting this together, every member of my staff, including my finance team and my lawyer, was helping me out, which I will remember for the rest of my life. People in Sri Lanka help each other at times like that. It is a beautiful thing to see. However, Sri Lankan hospitality could be more consistent, so I must be a strong leader to drive that and deliver. If I am paying an individual three hundred thousand rupees a month, and if that individual fails to follow instructions after being told many times, I must give that economic opportunity to someone else. We promote people on seniority. That also has to change. If some individuals are better and faster, they should get opportunities to grow as we can push them to greater heights. Our organizational culture is about consistency, quality, and efficiency.

Your leadership is pivotal to becoming exponential as a restauranteur. What leadership style do you bring to your business?

Japanese food is all about precision and attention to detail. Unfortunately, Sri Lanka is not known for attention to detail and attention to time. The only thing that we do on time is follow auspicious times. I have flown with four staff, three chefs, and my PR manager eighty-eight times between London, Paris, Tokyo, Australia, Singapore, Hong Kong, Delhi, Mumbai, Maldives, Seychelles, Dubai, and Abu Dhabi. I’ve been telling them to watch how people walk in those countries. They observed that those people walked fast. But I told them that it was not that they walked fast, but that we walked slower. I make them understand that we have only a limited number of hours to deliver and to make the maximum out of it. But things are improving. I try teaching people what they can learn. So, if I had to teach ten people, I’d instead teach two and have them do five tasks between each of them. That way, I make sure we reach the target of ten. However, I will not try to do ten tasks with one individual and end up doing only six. Because what I do is so new, only a few people can come from another industry and coexist with me.

Experience is essential as it brings the maturity that I look for. But most of the time, I would instead take a fresher and mold them. I have a saying at MOC that your blood has to become orange. It’s true. They become that. It’s not brainwashing; it’s about creating and adapting to a fast-paced workplace. And that’s the reason for our success. We are on point, and time is of the essence in our business. On the walls of the MOC kitchen hangs Dharshan’s Twelve Commandments, which are twelve rules to follow, and no one flouts that or changes anything because our work is all about consistency. I have to be strong to be able to deliver this. That’s the problem with Sri Lankan hospitality. I have several clocks at the MOC depicting the times of different time zones so that whenever I’m traveling, which I do now frequently, they know the appropriate time to contact me. I had to train them to learn by paying attention and working harder so they would contact me when I could look into issues. But that was a discipline I had to instill. So, as a leader, I teach my staff so they can complete their roles efficiently and effectively. I was born in Japan. I came to Sri Lanka. I always lived with English, Japanese, and Sinhala in my life. I always knew there was a time difference between countries three or four dishes, our flavors are different from Sri Lankan. But we shone because we used a fresh Sri Lankan ingredient and said no to freezers. How many other countries can do that? As we plan to open an MOC in Singapore, we are trying to practice our no-freezer policy there, and if we succeed, it will be the first restaurant in Singapore to achieve it. Being an engineer, I can push the limits. My mixed heritage and growing up surrounded by the ocean has allowed me to experiment.

Being an engineer, I can push the limits. My mixed heritage and growing up surrounded by the ocean has allowed me to experiment.

If we take the local food landscape, what can we do better?

Stop using MSG. Street food in Asia uses tons of MSG. None of my restaurants use it, nor can I eat food containing MSG. We are a country with enormous natural resources to make flavors naturally. We balance flavors, textures, and colors, which come with talent and mindfulness when we treat ingredients respectfully. It is more than simply running a restaurant that serves a menu. There is so much we can do to create a unique identity for our food.

With a few changes, we can make serving Sri Lankan food interesting. We can package the elementary packet or box of rice uniquely. Why can’t we make a difference by naming the fish or the rice served? We could give an identity to the rice, as rice harvested in Polonnaruwa or Anuradhapura in the Maha season. We have immense choices in how we offer our food. It’s all about paying attention to detail, and that makes a world of difference. We can do the same with Ceylon Tea, moving to something more from the typical tea served with and without milk. We have abundant local ingredients to offer a variety of choices, but first, we must respect the ingredients. They can’t be just part of everyday preparations. We must educate people on their importance and show how best to use them to serve a consistent dish. We have fresh products from the ocean, but we don’t bother to go deeper to create a bigger story for them. We must add value to that privilege.

What is the work culture in your restaurants since you represent two distinctly different cultures, Japanese and Sri Lankan?

I think my staff knows that we aren’t a democracy. It’s close to a dictatorship, especially in the kitchen. I can’t have second opinions about something we decided once. In our business, it’s all about execution and teamwork. I can best describe how we work through the role of a sports captain whose leadership has to shine through intense situations when they have to make quick decisions according to the realities on the ground, such as reacting to the different outcomes on the field and responding appropriately when the ball changes direction. Under such scenarios, the team leader or the teammates have no time to stop and take a vote on how they should respond. They have trained the team to respond accordingly. There is nothing dictatorial or undemocratic about such a setup. It is a must to win the game. Likewise, our business’s ground realities also change every minute and every day. Things may even change mid-sentence. I have to rely on a big team where each acts independently without expecting someone else to respond to a situation, and that’s how we get results. So, as a boss, I am very strong-minded, and I make sure my team knows that.

As I said, teamwork is critical to our success, and I have ingrained this in my teams across our restaurants. Creating Nihonbashi at the Port City was one such effort. I told my staff that I was building something I didn’t know. It does not exist anywhere, and I’m not copying something I have seen in another country. We will make mistakes, but I will need your hands on deck when the time comes. So, when we were putting this together, every member of my staff, including my finance team and my lawyer, was helping me out, which I will remember for the rest of my life. People in Sri Lanka help each other at times like that. It is a beautiful thing to see. However, Sri Lankan hospitality could be more consistent, so I must be a strong leader to drive that and deliver. If I am paying an individual three hundred thousand rupees a month, and if that individual fails to follow instructions after being told many times, I must give that economic opportunity to someone else. We promote people on seniority. That also has to change. If some individuals are better and faster, they should get opportunities to grow as we can push them to greater heights. Our organizational culture is about consistency, quality, and efficiency.

Being an engineer, I can push the limits. My mixed heritage and growing up surrounded by the ocean has allowed me to experiment.

Your leadership is pivotal to becoming exponential as a restauranteur. What leadership style do you bring to your business?

Japanese food is all about precision and attention to detail. Unfortunately, Sri Lanka is not known for attention to detail and attention to time. The only thing that we do on time is follow auspicious times. I have flown with four staff, three chefs, and my PR manager eighty-eight times between London, Paris, Tokyo, Australia, Singapore, Hong Kong, Delhi, Mumbai, Maldives, Seychelles, Dubai, and Abu Dhabi. I’ve been telling them to watch how people walk in those countries. They observed that those people walked fast. But I told them that it was not that they walked fast, but that we walked slower. I make them understand that we have only a limited number of hours to deliver and to make the maximum out of it. But things are improving. I try teaching people what they can learn. So, if I had to teach ten people, I’d instead teach two and have them do five tasks between each of them. That way, I make sure we reach the target of ten. However, I will not try to do ten tasks with one individual and end up doing only six. Because what I do is so new, only a few people can come from another industry and coexist with me.

Experience is essential as it brings the maturity that I look for. But most of the time, I would instead take a fresher and mold them. I have a saying at MOC that your blood has to become orange. It’s true. They become that. It’s not brainwashing; it’s about creating and adapting to a fast-paced workplace. And that’s the reason for our success. We are on point, and time is of the essence in our business. On the walls of the MOC kitchen hangs Dharshan’s Twelve Commandments, which are twelve rules to follow, and no one flouts that or changes anything because our work is all about consistency. I have to be strong to be able to deliver this. That’s the problem with Sri Lankan hospitality. I have several clocks at the MOC depicting the times of different time zones so that whenever I’m traveling, which I do now frequently, they know the appropriate time to contact me. I had to train them to learn by paying attention and working harder so they would contact me when I could look into issues. But that was a discipline I had to instill. So, as a leader, I teach my staff so they can complete their roles efficiently and effectively. I was born in Japan. I came to Sri Lanka. I always lived with English, Japanese, and Sinhala in my life. I always knew there was a time difference between countries because I experienced it as a child. I always knew there was an international country code for each country and the different currencies.

What I do is so new, only a few people can come from another industry and coexist with me. Experience is essential as it brings the maturity that I look for.

How come you are expanding while many in hospitality around the world are hiccupping?

The F&B industry is going through a difficult phase in Sri Lanka and worldwide. There are signs that ninety percent of restaurants are closing in Singapore, while I plan to take MOC to Singapore. Even Michelin-starred restaurants are closing in Singapore, where the dining landscape has been challenging, and many are departing. Rising costs are making it harder for restaurants to stay open.

The challenges in Sri Lanka are also immense. It’s getting tougher globally. But still, people have to eat and enjoy. MOC is present in the Maldives, Shanghai, Chengdu, and Bangkok, while we do pop-ups worldwide. Sri Lanka is the most challenging place to do restaurants. Our market is small, with diminished purchasing power. People would spend fifty dollars in metro areas of Singapore, Malaysia, and Bangkok, which is exponential compared to Sri Lanka. We have too many import restrictions, high taxes, and the rising cost of ingredients. But still, there are solutions to those problems. Through it all, we have built an identity with passion and are confident of sustaining it. Our journey has been to build a market for the food we serve. So, let’s be positive. We are not even one month at the Port City, but in one year, if I can reach a service charge of one thousand dollars in Sri Lanka at Nihonbashi, at least I have proven something.

How do you see the future landscape in Sri Lanka with the Port City as an opportunity?

Port City is a significant addition to Colombo, with the Indian Ocean at the doorstep. Securing such an attractive location anywhere else in Colombo with its space and other conveniences while providing a fantastic view of Colombo’s most significant real estate was a challenge. We are visible to every hotel in Colombo. I have a terrible habit of going to places no one has before. Galle Face Terrace was an unlikely location. Our earlier location posed certain limitations in terms of space, but we can do new things at our current location as I have designed it with plans in mind. Port City is a prominent destination and a great location poised for growth in the future. We are a standalone, and people come because they see us. And for the first time, Nihonbashi is visible to all. We have found a great location.