DR JB Kelegama

There seems to be a tendency in Sri Lanka to exaggerate the importance of SAPTA and its relevance to the country’s development. The authorities in charge of the subject are accustomed to giving glowing accounts of its potential and of making unfounded statements on its contribution to the country’s economy. Some official spokesmen have gone to the extent of announcing SAPTA to be a panacea for all our economic ills. Perhaps these hyperbolical statements reflect our eredu lousness regarding the efficacy of international action, our naive beliefs that international action is a substitute for domestic action. We seem to be reluctant to abandon our emotional commitment to the concept of economic cooperation among developing countries (ECDC), in spite of our disillusionment with such co- operation in areas such as joint action among producers in tea, rubber, coconut and pepper, regional trade expansion in Asia and the Pacific through the Bangkok Agreement, international action on commodities. and global system of trade preferences through UNCTAD and safeguarding interests of developing countries in the Uruguay Round. Thus, it is not surprising that hopes are now placed on another scheme of ECDC closer to home-SAPTA, although there is little to justify our hopes that it will make a substantial contribution to our economic development.

Sri Lanka’s Trade with South Asia

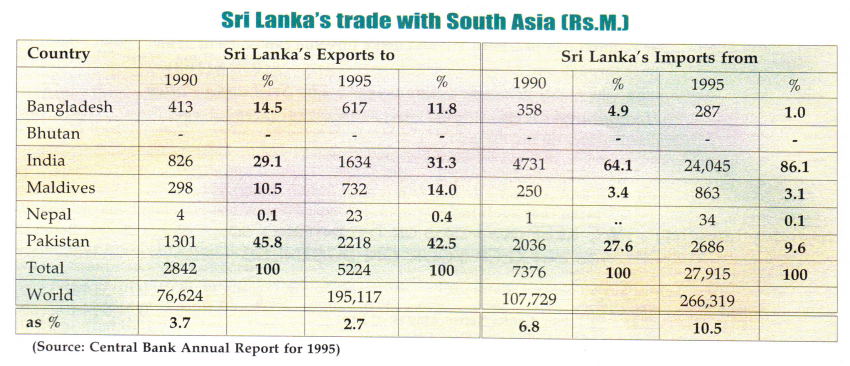

Sri Lanka’s Trade with other South Asian countries is relatively small; it constituted about 7% of her world trade in 1995. Her exports to SAARC formed 2.7% of her world exports while her imports from SAARC amounted to 10.5% of her world imports as shown in the table. Pakistan is Sri Lanka’s largest export market in SAARC accounting for 42.5% of her regional exports (mainly tea) in 1995, followed by India purchasing 31.3%. India is by far the largest source of Sri Lanka’s imports in the region, supplying 86.1% of her regional imports in 1995; Pakistan supplied only 9.6%. While Sri Lanka’s trade with Maldives is growing, her trade with Bangladesh and Nepal is subject to much fluctuation; there is no trade between Sri Lanka and Bhutan.

Sri Lanka is a net importer from SAARC in that her imports from SAARC exceed her exports to it. In 1995 for instance, her imports were Rs 27,915 million and her exports Rs 5224 million; exports were equal to about 19% of imports or her imports were a little over five times her exports. Second, it is significant that while the share of her exports to South Asia has fallen from 4.3% in 1985 to 3.7% in 1990 and then to 2.7% in 1995; the share of her imports from South Asia has risen from 6.4% to 6.8% and then to 10.5% in those years. Thus, South Asia has become less important as an export market for Sri Lanka in the last decade and more important as a source of imports. This resulted naturally in a widening trade deficit with South Asia.

Third, the rising imports from SAARC and the growing trade deficit is the result of the marked in crease in imports from India by as much as 408% in the last five years. The growing importance of India as a source of imports is also illustrated by the fact that India has become the second largest supplier of imports to Sri Lanka after Japan. From a traditional supplier of foodstuff, India has now become a major supplier of machinery and equipment, particularly in transport buses, lorries, small motor cars, three- wheelers, scooters and bicycles. With the technological improvements taking place in India, Sri Lanka is likely to purchase a greater variety of goods from India in the future and increase her imports further. This trend will operate whether there are trade preferences or not. Although it is a trade diversion, the benefit to Sri Lanka lies in the savings of foreign exchange resulting from the lower prices of goods from India (due to lower labor costs and freight).

Export-orientation to the West

South Asian countries particularly India, but there is

The raison d’etre of a preferential trading system, it should not be forgotten, is not trade diversion but trade creation. Selling goods which are exported to third world countries and which have a world market to SAARC countries instead is only a diversion of trade; it does not result in increase in production or contribute to the country’s economic development; nor does it increase the country’s foreign exchange earnings. From Sri Lanka’s point of view it does not really matter whether her current production of tea is sold to the Middle East or Pakistan(SAARC) if there is no difference in the price fetched. The real contribution of a preferential trading arrangement has therefore to be measured in terms of new trade and consequently new production resulting from it. The crucial question is whether SAPTA will contribute to the expansion of production or more favorable prices for existing exports or to the creation of new exports. There is little evidence that this is the case.

First, as Sri Lanka, like some other developing countries, is pursuing a policy of private enterprise- based and export-oriented development within a framework of free markets and free trade, the investors in new export industries are free to decide in what sector to invest in and there is no State intervention to persuade or induce them to invest in particular sectors. The new export industries selected by private investors are those which yield the maximum profits in the shortest possible time, and they invariably happen to be those producing goods for the vast and prosperous markets of developed or industrial countries of the West and Japan, e.g., garments, textiles, cut diamonds and jewelry, rubber goods, travel goods, footwear, ceramic products, fish and crustaceans. The largest new export industry is garments but almost all the garments are exported to the West.

Second, there is no market for Sri Lanka’s new export products in the South Asian markets as almost all SAARC countries are manufacturing the same type of export goods. For instance, garments is the leading export of Bangladesh and Nepal and a major export of India, Maldives and Pakistan. Similarly, cut diamonds is the leading export of India and fresh fish and crustaceans the leading export of Maldives and a major export of Bangladesh, India and Pakistan. All the export processing zones of SAARC countries are producing goods to be sold outside the region, often in competition with one another. In fact, Sri Lanka’s gherkin exports suffered a major setback on account of Indian competition.

Third, Sri Lanka is granting a variety of incentives to foreign capital, particularly transnational corporations to set up export industries in the country. Some official spokesmen of the government are persuading transnational corporations to invest in Sri Lanka as they can use SAPTA and sell their products in other

little evidence to show that any transnational corporation has considered using Sri Lanka as a manufacturing base to supply their products to the whole of South Asia. It is doubtful whether transnational corporations will establish manufacturing bases in Sri Lanka to supply the Indian market, when they can establish them direct in India itself. Besides, our labor costs are likely to be higher than that of India. Some of them have come here to establish import substitution industries such as Pizza Hut, Kentucky Fried Chicken, gas and lubricants while others have come here to exploit Sri Lanka’s cheap labor to manufacture goods at a lower cost for the industrial countries. These transnational corporations are increasingly locating their manufactures in low cost developing countries as the high labor costs in their own countries have eroded their competitiveness and profits. The products they manufacture are largely designed for their domestic markets and are not for the South Asian market. True, they create new exports but outside SAPTA.

Limited Supply of Export Goods

Thus, SAPTA by itself is unlikely to make a significant impact on our exports and economic growth. We may get trade preferences from our neighbors, but they may be of little use when we do not have a broad structure of production capable of producing a wide range of manufactured goods they require. Our agricultural exports have only a limited market in South Asia and we cannot expect them to contribute much to our economic development. In short, we must have the goods to sell if trade preferences are to be meaningful. The fact that we export so little to South Asia indicates that we do not have the goods demanded by our neighbors. This is best illustrated in the case of India where our exports are equal to a mere 7% of our imports from that country. Leave SAPTA alone, we should at least see how we can exploit the Indian market in the same way India is exploiting our market.

Trade preferences under SAPTA are likely to benefit India more than Sri Lanka and other member states of SAARC as it has a wide range of both agricultural and manufactured goods which are demanded in the regional market. India’s heavy industries are fairly well-developed and are now becoming increasingly capable of producing machinery and equipment for export. None of the other SAARC countries have such a broad manufacturing base. It is not India’s fault that she is in a better position to derive benefits from preferential trade. It is rather the fault of other SAARC countries for having failed to develop their own industries and diversified their exports as India has done.

Joint ventures with India

The largest country market in SAARC is that of India but Sri Lanka produces only a small fraction of what is required by this market. A promising line of action for Sri Lanka therefore appears to be to pro- duce those goods in demand in India at least in the near future, but this is not an easy exercise. First, a study needs to be made of India’s import require- ments in the years ahead on the basis of her pattern of economic development and second, there should be a careful selection of those goods which can be pro- duced in Sri Lanka, competitive in quality and price, to meet these requirements. Third, private firms, lo- cal and foreign, need to be persuaded to invest in such industries. The type of firms which may invest in these industries is likely to be different from the type which has already invested in Sri Lanka to produce goods for the developed country markets and which have little experience in the Indian domestic market. Further, even if they produce the right kind of goods, there is no guarantee that India will purchase them.

There are two types of foreign investors who maybe interested in setting up industries to produce goods for the Indian markets, provided Sri Lanka has the right conditions. The first is Indian industrial firms themselves who may consider establishing their subsidiaries or forming joint ventures with Sri Lankan business for the production of specific items they need if it’s cheaper in Sri Lanka. Hitherto, Indian capital had established subsidiaries and joint ventures to produce goods mainly for the Sri Lankan domestic market for example, sewing machines, ceiling fans, bicycles, restaurants, hotels but not to produce goods for the Indian market. The second is foreign multinational corporations operating in India which may wish to examine the feasibility of setting up subsidiaries in Sri Lanka to form a linkage with the Indian market. It is however, the task of the Sri Lankan business community, with encouragement and support from the authorities, to negotiate with these categories of investors. There is little evidence that any action has been taken in this direction so far. If Sri Lanka fails to exploit the opportunities provided by the Indian market in this way, it is doubtful whether SAPTA can help it to create new exports conducive to economic growth. Actually, priority should be given to creating exports if SAPTA is not to remain a mere agreement on paper.

It is time Sri Lanka changed its perception of the Indian market as one to sell its pepper, copra, cardamoms and other spices. These products have only a limited market even if India allows them to be imported without any restriction. Sri Lanka must think ‘big’ and study how its economy can be restructured to exploit the regional market, particularly India’s, by creating new exports. The kind of products India buys from abroad is illustrated by what she imports from South Korea, a leading newly industrialized economy: polythene primary form, TV picture tubes, tin plates, telecommunications equipment, zinc alloys, iron plates, organic chemicals, rails, steel plate, steel coils, medicines, electronic microcircuits, electric machinery parts, etc. Similarly, India’s main imports from another newly industrialized economy-Singapore – include the following: TV picture tubes, paper board, accounting machines, telecommunication equipment, electronic microcircuits, polyethylene primary forms, ball bearings, printed books, electrical machinery, switch gear and parts and components of different machines and equipment. All these goods are machinery, equipment and intermediate products – not consumer goods. What this means is that Sri Lanka should develop rapidly to become a newly industrializing country herself with a broad industrial base and diversified export structure so that it could meet the growing regional demand for new manufactures using trade preferences for support.