Tying remuneration policies to drive the correct behavior and corporate accountability is the lesson from a recent pay cut imposed on the CEO of a leading Singapore bank.

Words Jennifer Paldano Goonewardane.

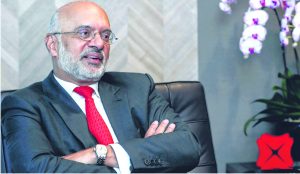

In February 2024, the CEO of Singapore’s biggest bank, DBS, was told of a 30 percent cut to his variable pay for 2023 by the bank’s Board. Headquartered in Singapore, DBS is a leading financial services group in Asia, with over 280 branches across 18 markets. Anyone would reckon the slash was in response to poor performance and bottom lines. But Piyush Gupta, at the bank’s top post since 2009, has been a remarkable and respected leader with multiple accolades for growing the bank’s fortunes under his stewardship. So much so that the windfall in 2023 was spectacular. DBS made a profit of S$ 10.31 billion in 2023, a 26 percent increase from 2022, which recorded a profit of S$ 8.19 billion. Its 2023 fourth-quarter net profit had surged beyond expectations by two percent to S$ 2.39 billion compared to S$ 2.34 billion for the same period in 2022.

Then, why was Gupta targeted? What triggered the response? In March 2023, DBS encountered a ten-hour digital service outage, preventing customers from making transactions and ATM withdrawals. However, their woes had been ongoing before 2023 and continued intermittently after the March 2023 major outage. The authorities in Singapore responded, and so did the bank’s Board. The senior management was held responsible for the lapses with cuts to their variable pay. As a result of the cut, Gupta would lose S$ 4.1 million in variable pay (outside of the base pay), which consists of cash bonuses and deferred shares. Gupta took the most significant slice of the cut, while others in the bank’s senior management team received a 21 percent variable pay cut. In a contrary action, the bank’s junior employees will receive a one-off bonus to meet the rising cost of living, for which the bank has allocated S$ 15 million for 2023.

DBS probably faced the threat of losing trust when its technology displayed loopholes in its ability to deliver on customer needs.

The story hit the headlines in February this year, picked up by all the leading global business and financial news outlets. It has become a classic case of holding financial institutions and corporate leadership accountable for incidents. The irony of the situation is that DBS, also the biggest bank in Southeast Asia, was decorated as the World’s Best Digital Bank by business and finance publication Euromoney. That is in addition to multiple honors of being named the World’s Best Bank numerous times by leading global financial publications, the Most Innovative in Digital Banking by The Banker, and among the Top 100 Best Workplaces for Innovators by Fast Company. DBS has had the highest credit ratings globally. But all those titles did not matter to Singapore’s financial regulator, the Monetary Board of Singapore, who reprimanded DBS for the digital disruptions, calling it unacceptable and accusing it of falling short of expectations. Banks have a four-hour timeframe to restore their systems, which DBS could not realize. First, Monetary Authority of Singapore requested a comprehensive investigation into the incidents and expressed concern about how the bank handled affected customers and transactions. The bank’s chairman and CEO apologized for the disruptions, and the CEO pledged to rectify the glitches and strengthen its processes.

In response, the financial regulator imposed restrictions on the bank’s activities for six months, including a ban on acquiring new businesses. The bank received a directive to focus on restoring the resilience of its digital platforms. The bank also moved swiftly and, by November 2023, set up an S$ 80 million budget for this purpose, aimed at strengthening its technology to prevent future disruptions by being able to anticipate service disruptions better and employ swift responses if they reoccur by offering alternative payment channels and restoration of services. It has hired a head of technology risk and will follow up with the appointment of a chief information officer.

Singapore’s financial regulator and the bank’s Board’s actions reinforce investor confidence in the institution and system. They reflect the city state’s overarching thrust of maintaining an unsullied governance culture across the board, in state and private entities, holding everyone, irrespective of rank and file, to account and take responsibility for their actions, as demonstrated in recent government steps against legislators for alleged corruption. It also indicates that the authorities refuse to cow down to financial strength. Their actions starkly contrast with the aftermath of the 2008 global financial crisis, where none of the chief culprits that led the companies that caused the crisis have been hauled before courts to hold them accountable for the colossal damage that destroyed lives everywhere, none have been criminally charged or indicted. The reason, as alleged, was their money power because they were industry titans with connections to lawmakers and the best legal teams. Stories abound of leading global banks facilitating money laundering for drug rings, corrupt politicians, tax evaders, and sanctioned states, getting away by paying hefty fines to regulators and continuing operations. Only in a few instances have their top executives stepped down.

In contrast, the Monetary Authority of Singapore stood its ground before its biggest bank, uninfluenced by its financial strength, Board power, and global spread, doing its job independently and unflinchingly. By doing so, the message is clear – to hold people to account means that they need to be cognizant that actions have consequences, and unapologetic immunity is not an option. Analysts contend that senior executives must realize that there are consequences, mainly when their pay depends on performance, which could drive questionable behavior. Singapore banks practice pay-for-performance. Some have warned that practice may cause their leaders to scurry for optimum results, running the risk of resorting to excessive practices to lay claim to a substantial compensation package. It may even encourage dishonest behavior.

Further, analysts say that culture, governance, and remuneration are significant and closely linked causes of misconduct. They add that often CEOs, operating in a culture of self-serving, tend to take cover for mishaps and missteps by highlighting their role in steering the company towards better performance and bottom lines while trying to attribute issues and poor performance to external factors, such as was the case with DBS where Gupta described the digital outages as ‘tech instances’. In contrast, he said the bank has proven its strength and standing with extraordinary results, of which he was a significant contributing force.

According to analysts, DBS executives, including those in several other Singapore-based banks, draw hefty compensation packages compared to executives in larger banks in countries like Australia. Thus, the degree of onus on the seamless delivery of services and bottom lines is evident. At the core of those benefits is impeccable excellence, where breaches earn consequences. In the final analysis, investor interests precede everything else. Vital to safeguarding investor interests is a consistent and improved customer experience that ensures their retention and the pull of new ones. DBS probably faced the threat of losing trust when its technology displayed loopholes in its ability to deliver on customer needs. And being the highest-paid bank CEO in Asia Pacific for 2022, with S$ 15.4 million in compensation, a package that will still be substantial in 2023 despite the cut, Gupta has a lot on his hands to deliver.