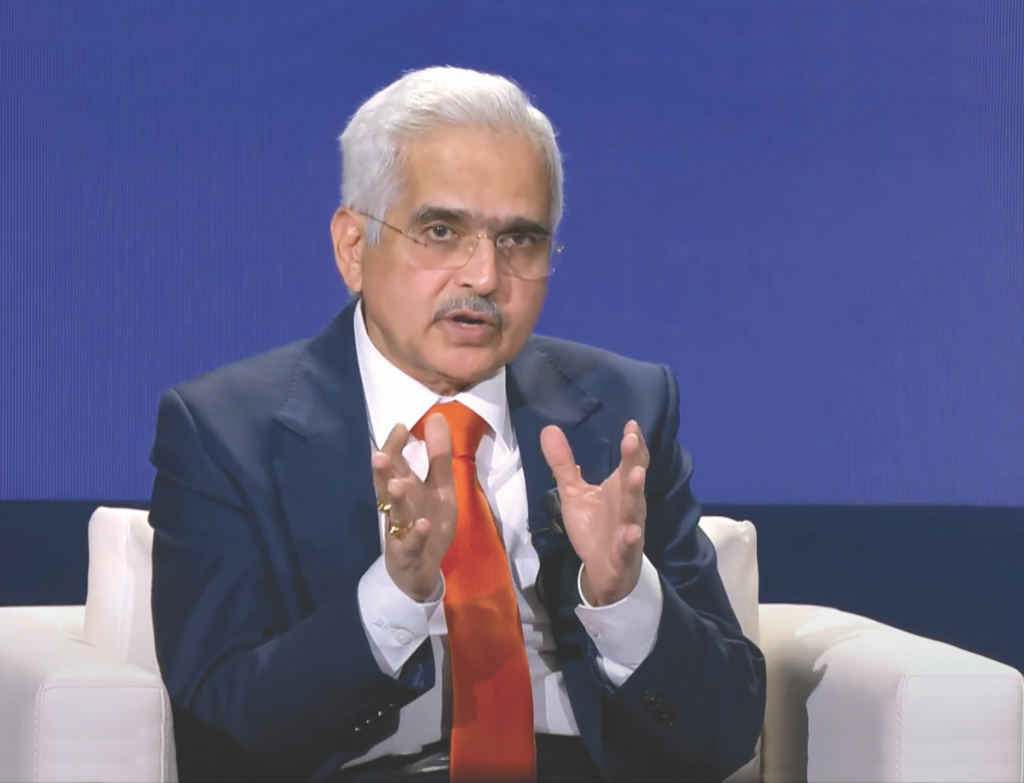

During the World Bank Group – International Monetary Fund Annual Meetings in October 2023 in Marrakech, Morocco, among some of the live events was “Governor Talks” that saw central bank heads sit down to speak on their country’s economies. During one such event with Reserve Bank of India Governor Shaktikanta Das, the focus was on how India tackled the impact of global shocks effectively, her experience with digitalization, in particular, with pioneering the Central Bank Digital Currency and how it has helped to improve financial inclusion, innovation, and efficiency.

Words: Jennifer Paldano Goonewardane.

Shaktikanta Das, Governor of Reserve Bank of India and Krishna Srinivasan, Director – Asia and Pacific Department, IMF.

Calibrated responses

The last five years have been a period of multiple shocks reverberating through India’s economy, which the country has tackled with overwhelming maturity and clarity. The RBI and the Finance Ministry have worked in tandem to respond to them, a strategy the Governor said was primarily responsible for the world’s fifth-largest economy to demonstrate its resilience and ability to respond to those challenges effectively. India’s financial sector worries did emerge in the second half of 2018, but the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic was enormous because of its global scale. Through it all, India was one of the worst affected by the pandemic and its variants. However, admirably, the institutions bestowed to manage India’s economy responded with purposeful solutions with well-thought-out targets. Governor Shaktikanta Das opined that several well-thought-out measures implemented in a coordinated, calibrated, and targeted manner by the RBI and the government as the monetary and fiscal authorities helped India stave off inflation spikes, with just moderate increases when it did and declining faster than in other parts of the world. The response avoided an excessive fiscal expansionary policy and excessive fiscal support compared to advanced economies. The well-calibrated measures helped the financial markets function generally despite the constraints of the pandemic. Injecting liquidity, reducing the Repo rate by 215 basis points on top of a few earlier rate hikes, reducing interest rates, and supporting banks and non-banking lenders, first with a six-month moratorium and a resolution framework for loans under stress, were some of the interventions introduced to usher in stability. The focus of all those measures was management, the Governor pointed out. For instance, every liquidity injection was accompanied by an end date or a sunset provision, with specific periods of one year or three years, with no dilutions or compromises to collateral standards. The sunset clauses for banks and non-banking institutions remained unchanged throughout. The central bank did, however, reduce the cash reserve ratio, benefitting all the banks, which was phased out over two months to make the process smoother. On their part, the Governor pointed out that the banks were aware of their obligation to return the liquidity within the stipulated timeframes, allowing them to plan their liquidity management better. Simultaneous to these measures, supply-side management and government initiatives during this period helped keep inflation under check while any spikes got pushed back. By maintaining a continuous working relationship with banks and non-banking financial institutions through supervision and regulatory mechanisms, the RBI ensured their resilience and quick recovery, negating the need for deadline extensions.

Governor Shaktikanta Das opined that several well-thought-out measures implemented in a coordinated, calibrated, and targeted manner by the RBI and the government as the monetary and fiscal authorities helped India stave off inflation spikes, with just moderate increases when it did and declining faster than in other parts of the world.

When India was reaching a semblance of normality against the backdrop of well-coordinated fiscal and monetary policy responses to the pandemic-induced economic disruptions, the war in Ukraine produced a new set of challenges for its planners. The RBI monetary policy statement in February 2022 forecasting a 4.5 percent inflation for the financial year April 2022 to March 2023 would have remained stable had not the war in Ukraine broken out, which sent prices of commodities, especially crude oil, skyrocketing, accompanied by supply chain disruptions to accessing wheat and cereals, driving global prices to rise steeply. Despite its wheat surpluses, India saw its domestic prices increase due to its linkages to the international market via wheat exports. In addition, the war disrupted India’s import of edible oil from the Russia-Ukraine region. In the final analysis, inflation in India rose much later than other countries elsewhere for two reasons – a well-calibrated and managed fiscal and monetary response of the RBI and Finance Ministry and the war in Ukraine that created a new scenario of challenges to global supply chains and disruptions that impacted commodity prices everywhere, which saw India’s inflation increase in its aftermath, but later than other countries.

Achieving price and financial stability, and growth amid the shocks

The Indian economy has been pitted against a sequential series of shocks in the last five years, some of which overlapped. It started with the failure of a sizeable non-banking lender in the second half of 2018 that gave way to significant stress in financial markets, bringing its activities to a near standstill, accompanied by liquidity pressures, leading central bank officials to dedicate 2019 to manage the knock-on effect, which it achieved by launching a strict regimen at the Governor’s level of monitoring the top hundred non-banking lenders weekly while injecting liquidity. Beholden on the RBI was to avoid any more such non-banking institutional collapses during this time. To that end, the RBI engaged in rigorous supervision of non-banking lenders by working closely with them and initiating corrective changes with stricter regulations to the hitherto lenient regulatory architecture of non-banking lenders.

As the previous crisis eased through RBI’s stringent intervention throughout 2019, 2020 opened to the COVID-19 pandemic, which spanned the next two years, wreaking havoc with the variants, and just as the pandemic showed signs of slowing, the war in Ukraine followed. India has managed to manage the crises of the last five years by adopting a proactive approach by identifying the problem and acting upon it before it could become full-blown. For instance, amid the lack of clarity about what would unfold in the days and months ahead when the world woke up to a virus spreading fast by March 2020, the RBI announced a moratorium on loan repayments to banking and non-banking lenders. The RBI was clear that it would do it for six months but plugged it into two phases: first, a three-month period, which would extend for a further three months depending on the behavior and direction of the virus. The RBI made the moratorium offer even before the market and institutions demanded such a relief. India introduced a COVID-19 resolution framework to address the problem of stress in banks; it was, however, not an open-ended framework that allowed banks to restructure loans according to their whims. An RBI-instituted committee prescribed specific financial and operational parameters that the lender had to achieve during the post-loan restructuring period. For instance, during a stipulated loan restructuring period, the borrower was responsible for meeting financial and operational parameters, such as bringing in additional capital and making internal adjustments to the business.

The RBI has also been innovative in its measures. During this period, the RBI completely recast the financial sector regulatory architecture with new governance guidelines for the banking sector, State and private, making it mandatory for them to have a chief risk management officer at a certain level, issued guidelines for the risk management committees and audit committees of the RBI Board. For the non-banking financial institutions, the RBI introduced a scale-based regulatory framework, categorizing the institutions into four depending on their size and complexity, new guidelines for digital lenders and asset reconstruction companies, and core investment companies, thereby capturing every sub-sector operating in the financial market under a new regulatory framework.

India introduced a COVID-19 resolution framework to address the problem of stress in banks; it was, however, not an open-ended framework that allowed banks to restructure loans according to their whims. An RBI-instituted committee prescribed specific financial and operational parameters that the lender had to achieve during the post-loan restructuring period.

Further, the RBI has tightened its supervisory role since, no longer waiting for the symptoms as a warning sign but through its early warning exercises, the RBI dives deep into the business models of banks and non-banking lenders to identify the potential risk areas, sensitizing them straightforwardly rather than trying to micromanage the situation. The early warning mechanisms were in place before this, but the RBI has since improved them.

The Governor spoke of India’s unrelenting pursuit of consolidating its foreign reserves since the onset of a volatile period beginning in 2019, increasing it by more than seventy percent, close to 600 billion dollars, which was close to 400 billion dollars in 2019. The increase, said the Governor, happened because of a conscious decision to build reserves as a buffer or insurance against the spillover risks. The argument for foreign reserves made sense – heavy periods of capital outflows can follow excellent periods of capital inflows, under which every economy, especially the emerging markets, and developing economies hit the hardest by the consequences of spillovers and global events, must look after themselves. India, cognizant of this fact, even with a huge population and an enormous economy, understands the importance of being self-reliant and self-dependent with a solid reserve base, and to that end, has focused on consolidating its reserves, which has rendered immense confidence to the market that whatever the challenge, India will be able to meet its external obligations.

An excellent example is when the US dollar appreciated in the aftermath of the Ukraine war. The currencies of many emerging markets depreciated, but the Indian rupee did not decline as much because of the market’s confidence that India, through the RBI, will be able to meet its external obligations. During the crisis, India intervened in the market, buying and selling dollars depending on the market’s direction. However, the objective was not to fix the Indian rupee to remain at a particular level compared to the dollar. The RBI’s aim, said the Governor, was to prevent excessive exchange rate volatility by making the Indian rupee stable and achieve an orderliness to depreciation or appreciation depending on the overall global and domestic situation, measures that all central banks should follow. While the RBI speaks openly about such measures, he decried those agencies that label such market interventions as manipulation and place such countries on a watch list, the motives for which should be considered from a view of the entire scenario.

Achieving monetary and fiscal coordination

Central bankers often lament issues in coordination with fiscal authorities on meeting monetary policy objectives. India is a lesson on how this could work in the real world to achieve national goals. How else could an economy the size of India rein in the challenges of an extended period of crises if not by running a coordinated effort between the RBI and the Finance Ministry? The Governor pointed out that India managed inflation through coordination, understanding, and engagement between the government and the RBI. The sudden increase in vegetable prices prompted by extreme weather changes that sent inflation rising steeply to 7.8 percent in April 2022 is an example of each institution’s important role in managing and controlling a crisis. They coordinated to play their respective roles. The RBI and the Finance Ministry knew that the rise in inflation was a temporary spike forced by the increase in vegetable prices, which would moderate after two months; hence, the situation did not demand rate changes, which had been at a pause. During this volatile period, the RBI actively engaged with the government, which adopted specific measures to bring down vegetable prices, while the RBI upheld market confidence by managing liquidity and keeping rates unchanged. As a result, inflation had declined to 4.6 percent in the first quarter of 2023.

Therefore, in India, active coordination between fiscal and monetary authorities has helped mitigate situations, a working relationship that has prevailed not only during times of crisis but remains a constant, an essential ingredient for results. Both agencies work for the economy, which demands conversations, engagement, and coordination as the central bank has to rely on the government to amend laws, which the government apparatus has teamed up to implement at the request of the RBI. This working relationship has helped the country face the vicissitudes of several years. This working relationship, said the Governor, is essential at all times. Every central bank should have decision-making autonomy while maintaining channels of communication open for constant conversations with the Finance Ministry on matters of national importance.

Introducing Central Bank Digital Currency and its role in financial inclusion

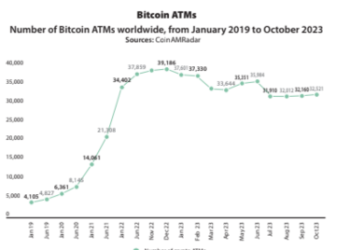

As a pioneer in digitalizing the financial market, India leads the frontier in digital payments, exceeding ten billion monthly transactions through its Unified Payments Interface (UPI), which processes over 300 million daily transactions. As a leader in financial digitalization, RBI’s next big move, driven vigorously by Governor Das, is to make CBDCs mainstream. CBDCs are touted as the world’s future currency, forcing countries and their central banks to spearhead efforts to mainstream them. Moreover, CBDC, pointed out by the Governor, is the ideal alternative to the stablecoins and cryptocurrencies that various individuals are plugging. Given their ambiguity, the RBI has adopted a cautious approach to their promotion and usage, especially in interpreting and understanding their consequences. The fundamental question on using stablecoins and cryptocurrencies is whether governments and central banks are comfortable with private currency, as currency is a sovereign function delegated to the central banks. The Governor stressed the need for greater clarity on new technology products styling themselves as significant innovations and their negative consequences for domestic and global financial stability and domestic and international monetary order. They pose a real threat in facilitating terror financing and money laundering, which could lead central banks in emerging markets to lose control, exposing their unstable nature. That makes it a central bank’s prerogative to gauge the risks of stablecoins or cryptocurrencies before rushing to legitimize them. It makes CBDCs the safest alternative as the world moves towards using technology in financial transactions. CBDC can facilitate efficient, cost-effective, and faster payments across jurisdictions and borders.

The RBI launched a pilot project for its ‘Digital Rupee’ CBDC on wholesale and retail transactions in late 2022. Its initial pilot on wholesale CBDC was launched in November 2022, followed by a retail CBDC pilot in December of the same year. The RBI introduced a wholesale CBDC pilot to settle secondary market transactions in government securities, and the RBI allowed the use of wholesale CBDC to settle government bond transactions in the secondary market. The RBI extended the wholesale version of the CBDC to the call money markets. A limited number of partner banks are participating in the wholesale CBDC pilot project. Thirteen banks are participating in the CBDC retail pilot project, with over a million users and over 300,000 merchants accepting payments in CBDC, making it one of the most significant CBDC pilots outside China. A testament to CBDC’s transformative nature is the inclusion of India’s small-scale vegetable vendors into the CBDC retail pilot project. The RBI hopes to accelerate the use of CBDCs among merchants and consumers by linking the CBDC wallets to the UPI through an interoperable QR code implemented in July 2023, thereby improving the system’s efficiency and limiting the risks. It is a learning experience, said the Governor, with daily new challenges driving the RBI to understand better CBDCs use in transactions and apply remedies while taking it forward through a carefully crafted approach to developing it into a fully-fledged payment mode. India is currently in discussion with countries exploring similar efforts. With the pilot project entering its first year of completion with many lessons learned, the Governor said that the RBI is confident that CBDCs can be the most effective and efficient mode for cross-border payments in particular and domestic transactions, especially as an opportunity for a more inclusive financial landscape where the unbanked will be able to access the formal financial system through CBDCs.

Shaktikanta Das, Governor of Reserve Bank of India.

Krishna Srinivasan, Director – Asia and Pacific Department, IMF.