Methods that yielded success yesterday are sure recipes for disaster tomorrow

Most organizations are designed to operate in an environment of stability and growth. That was wonderful when there was lots of stability and lots of growth. What do they do when customers, competition, and constant change demand flexibility, and split-second responses? They flounder and stumble, what else?

If nothing had really changed, why would the local Honda dealers place a full-page ad the other day, announcing that their Japanese principals had agreed to absorb the Dh 10,000 increase in their best selling Accord’s costs, to offset the effect of the mercurial rise of the the Japanese yen? The metal benders of Detroit are giving their old adversaries a real run for their money, that’s why.

The majority of organizations today owe their structures to the American railroad companies of the 1880s who designed business bureaucracy. It was based upon the need of that time. Hammer and Champy describe it elegantly in Reengineering the corporation with these lines: “To prevent collisions on single track lines that carries trains in both directions, railroad companies invented formalized operating procedures and the original structure and mechanisms required to carry them out. Management created a rule for every contingency they could imagine, and lines of authority and reporting were clearly drawn. The railroad companies literally programmed their workers to act only in accordance with the rules, which was the only way management knew to make their track systems predictable, workable, and safe.”

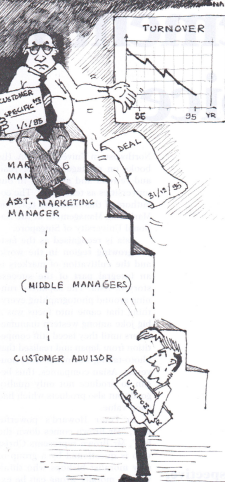

Tom Peters writes to say that. this philosophy was so deeply embedded that as recently as in 1986, a Union Pacific Railroad (UPRR) track inspector, had 8 levels of bureaucracy above him in operations, to communicate a customer-owned railroad siding problem. Having laboriously crept up those eight layers, the information would then have to leap across a great divide to UPRR’s sales and marketing people, at which point it would slowly seep down four levels before the customer would hear about the problem, assuming the customer was still around! Snakes and ladders stuff, eh? Why? Because UPRR bureaucracy prohibited railroad inspectors from talking directly to customers. The railroad inspectors were jokers in the pack, not to be entrusted with serious stuff like talking to customers. That was the job of sales and marketing, you see. What did all this song and dance contribute to? Delays and additional costs, not to speak of customer despair. On seeing this state of affairs, the late Mike Walsh, who took over as UPRR’s CEO in 1987, gasped, gulped and then set things right by eliminating six management layers and 800 odd middle managers from the UPRR operational Jungle Jim. How long did he take? 120 days.

What happens now? The customer and track inspector talk to each other freely. The inspector resolves the problem on the spot. How come? A Customer Action Team (CAT) has been set up to develop processes for “getting people together at ground level and giving them responsibility and the necessary control to solve the problem” Rocket science? No, commonsense.

What does the old style do? It creates perfect functional silos, where people are busy guarding turf instead of attending to customer’s problems. Bureaueracy is so wonderful for the psyche. You go to work every morning, delay everything you can, step on as many toes as possible, and return home in the evening, exhausted but exhilarated. I didn’t let the marketing guys have their way, we set up a committee to can the proposal, ha ha; or, Boy, the HR (Human Resources) manager had a fit at the end of the meeting, I really socked it to her. Real work hardly ever gets done. The bureaucracy at UPRR had reached Nobel Prize winning proportions when Walsh discovered to his horror that a memo sent by him two weeks before arriving at a repair shop in Arkansas, asking people to submit questions for discussions at the gathering, had been posted only the day before his visit. Why? The manager of the shop sent the note to the GM in Texas, who sent it to Omaha, where it sat for a couple of days, before being okayed and sent back to the shop. What was okayed – The CEO’s visit! YUK!

Can you recognize shades of UPRR in your outfit? Maybe it isn’t so bad, maybe it’s worse. How responsible are you for this state of affairs?

The trouble is, even the railroads have changed, but most businesses haven’t. Bureaucracy is so warm and soothing for the people in it, and who in his or her sane mind would want to dismantle it?

These systems were fine when companies could pass off high costs to customers, when dissatisfied customers had nowhere else to turn, when in the absence of new products customers simply had to wait. No Longer True.

So what’s the problem? Simple – we are entering the twenty-first century with companies designed during the nineteenth century, to work well in the twentieth. To quote Sumantra Ghosal of INSEAD, “You cannot manage third-generation strategies in second generation organizations with first-generation managers.”

Remember Charles Handy’s simple formula for organizational effectiveness Cut your staff by half, empower the remaining half to produce three times as much, and pay them twice as much. Everyone shall live happily ever after.

CEO’s have to lick their lips, get their blow torches out, put on their safety hats, and start asking some serious questions like Am I adding value? If so, is it positive? Who else agrees with my assessment of myself? What about the layers upon layers of managers between me and the troops? What are they actually doing? Checking others’ work? Holy smoke, what value does that add? Think it’s time to bring the ax out of the closet?