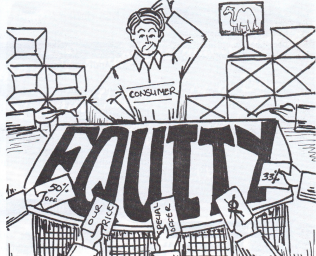

It seems to be the catch. word of the ’90s. Every one talks about it, every company tries to safe guard and build it. But what is it all about? Is it actually what they say it is? Or is it a myth?

The idea of brand equity started off as something like the good will that our forefathers sold when they left their stationery retail store; brand equity was a financial concept, like goodwill. Then, somehow, brand equity expanded and now it is more or less a grab bag of all the assets, usually intangible, that a brand musters. Since brand equity now means so many things, financial and otherwise, it is becoming almost unusable as an instrument to solve the major problems that brands now have.

Whatever be the case, brand equity has been proposed as a way of differentiating brands and in creasing customer loyalty, and as an stable emotional base on which to build extensions and new brands.

One proposed key measurement of equity is price inelasticity; in fact, some marketers have proposed that equity is just another word for price inelasticity. Many schools of thought now agree, that equity is something more. Equity should be seen as the special relationship that a person has with his or her brand Equity is slowly built and should withstand competitive pricing changes to some point.

The recent changes in the cigarette and detergent markets internationally, have mooted the question of just how deep that brand relationship is when prices change. Cigarette brands have traditionally been the most stable, and brand users have been the most loyal for any branded product.

A study conducted by J Walter Thompson in the US showed that cigarettes, followed by beer brands, were the most resistant to price changes of a wide range of branded products. In addition, the equity built by Marlboro (and) more recently by Camel) in the US was a standard referred to by both management professors and marketing professionals.

But what happened? Price brands have captured a major part of the US cigarette market, about 30% at last look. In response, major brands have slashed prices, Marlboro being the first. Other manufacturers seemed undecided initially, only to follow suit later on.

A similar situation occurred in the Middle East in the recent past This was when Unilever launched its OMO brand to take on the undisputed market leader “Tide” of Procter and Gamble (P&G). This low-priced OMO brand soon accumulated great market shares within no time. The P & G executives were too complacent thinking that ‘Tide’ equity is too strong to get affected by such new entrants competing on a price advantage. This myopic view however proved a little too costly for them; Tide” lost major shares and revenues. In retaliation, they started a discount campaign on both “Tide’ and ‘Ariel’ to regain some market share.

Procter & Gamble had to reduce their prices on “Tide’ in the US and the European markets which also started facing stiff competition from local price brands.

On another front, Coca-Cola has recently started offering their classic drinks at reduced prices in their pursuit of taking market shares from arch rival and market leader Pepsi.

What’s going on here? Are these equities very fragile? Have they been abandoned in a management panic? Or is this a rational long-term solution? Only future. market figures or an exposé by a company defector will tell us for sure. The fact is that managements in these cases have decided partly to leave equity as a form of franchise preservation.

That leaves us with the larger issue: Is brand equity a myth?

Is it a kind of demagoguery to persuade manufacturers that advertising and marketing work even if sales do not go up immediately? At first sight, it would seem so. Perhaps, the Marlboro case is not the text book case it has become over the years, and maybe we can learn the following canons about brand equity from the turmoil in the cigarette market:

☐ Despite the need for long term equity development, equity may wear out, may turn into wall- paper there, but not seen. That is something worth exploring.

☐ Equity must be unique, at least as much as possible. Marlboro originally offered a new taste of individuality and freedom in a world of machine-like conformity. That was something special for a brand in the late ’50s, but now it is not so unique.

Beer brands make the same offer. Automobile brands do it. Jeans and athletic shoes do it as well. Even underwear brands do the same. One need not turn to a cigarette brand to make that equity connection when other, safer alternates are available.

This raises a difficult question. In this crowded world, can a brand find any equity connection that uniquely meets consumer needs? Answer: Yes, but it is getting very hard. Perhaps one answer is to make the equity connection more precise and segmented. The tighter the personal needs met by an equity, the less likely that it will be duplicated.

☐ The price range for which. equity will help ensure inelasticity is probably shrinking. That means marketers must be prepared to have flexible equity/price strategies rather than rely on equity strategies alone.

Does this situation mean that equity does not work? Absolutely not. It probably means that equity alone is not enough to push forward or save a brand in these competetive times. Equity is one tool in a marketing arsenal. It must be integrated with quality strategy distribution strategy, and pricing strategy for total brand health and growth.

What Marlboro signals is the end of marketing laziness. As the idea of brand equity has developed, it has become a substitute. for flexibility, for complex marketing thinking. Equity has become a simple solution.

But the market is not simple; nor should our solutions be. Equity alone is not robust enough to save a brand. Equity along with other marketing elements can however do it.