Twenty years have lapsed since the day that I walked into N U Jayawardena’s office, having been informed by my then employer, Coopers & Lybrand (C&L), that he had specifically requested to see me. Jayawardena had read several reports I had written as a Senior Consultant at C&L under a USAID sponsored private sector development programme. By the time I walked out of the meeting, he had offered me a position at his new creation, Sampath Bank. As an impressionable youth in my 20s, I was naturally drawn to his intellect and enthusiasm towards transforming the country’s banking and financial services industry.

by Thilan Wijesinghe

At the time of accepting his offer, there were those who forewarned me of NU’s temper tantrums! Notwithstanding, I joined Sampath Bank as Senior Executive, Development Banking and later assumed the position of Manager Strategic Planning and Special Projects, a position I held until my resignation in February 1992, to pursue entrepreneurial interests. Yes, I did witness several of the NUJ outbursts, and yet, ‘survived’ inviting his wrath, save one occasion, when I received a call at 5:30 a.m. – a regular occurrence. NU sounded decidedly testy at an error I had made in forecasting the profitability of a new business he was contemplating at the time. He pointed out that I had made one error in the spreadsheet, and that, in the 6th year of the forecast ! I recall being awed at how he was able to identify this error and its impact on the project’s returns, despite my having the benefit of a PC and Lotus123 software. It underscored NU’s ability to grasp both the macro and the micro, and the fact, at over 80 years at the time, his mental faculties were razor sharp.

Working under NU certainly taught me one cardinal principle that, even today, I impart as advice to new jobseekers. Always seek to work for bosses from whom you can learn and stay one step ahead by cultivating the ability to anticipate your superior’s expectations. In particular, be able to interpret and communicate your position in a manner that your superior understands, in the required level of detail and analysis. Very simply: ‘do the homework on your boss.’

I have always maintained that my three-year stint as a protégé (so I was called) of NU was equivalent to a Masters in Business Administration. In fact a thought I was harbouring at the time of pursuing an MBA in the US was shelved in view of the intellectual stimulation and challenging work environment provided by NU. I did not again need a university library to pursue knowledge: NU’s own study at his Cambridge Place residence, where I have spent innumerable hours, was home to thousands of books on Economics and Business. Without doubt, this was the best library in Sri Lanka for a business student!

In Particular, Be Able To Interpret And Communicate Your Position In A Manner That Your Superior Understands, In The Required Level Of Detail And Analysis. Very Simply: ‘Do The Homework On Your Boss.’

Moreover, NU, harnessing his vast knowledge of the social and economic fabric of Sri Lanka, penned dozens of erudite articles on subjects ranging from economic policy, banking, legislation, agriculture, gems, etc. These articles covered just about every facet of macro and micro policy action that was required to enhance Sri Lanka’s economic prospects. NU gave me many of his writings to read – which I did assiduously. Again, these were more relevant for my own learning than any course in Public Policy, Government or Taxation I could have followed at Harvard Business School or London School of Economics! (I did struggle though with NU’s penchant for use of the comma in his writings and consequently the length of his sentences!)

NU also exposed me to facets of Sri Lanka’s archaeological history. I recall being introduced to Roland Silva, then Director General of Archaeology and Chairman of the Central Cultural Fund (CCF), in which NU announced that I would be ‘loaned’ to the CCF from Sampath Bank to assist in the preparation of the five-year funding plan for the restoration and preservation of Sri Lanka’s cultural monuments. After two months of virtually full-time work, I did produce the required plan, which was duly published in 1991 and accepted by the authorities, along with a discourse titled: ‘A Proposed Methodology for Measuring the Economic Value of Cultural Monuments,’ a study on the economics of conservation and cultural tourism, published by the International Council on Monuments & Sites (ICOMOS). I have always valued these works along with the five-year corporate plan I completed for Sampath Bank in December 1991. These to me were the equivalent of MBA theses to earn a ‘degree’ from what I would call the ‘NUJ University of Economics & Business’! Thank you, Sir, for the knowledge you bestowed on me.

NU also equipped me with ‘soft skills’ that holds me in good stead even today. One was his unwavering work ethic. Up at the crack of dawn, NU would be at his desk. If a question arose in his mind on a matter of business, a 5am or 11pm phone call could be expected. Whilst few, sans the likes of late President Premadasa, demonstrated such focus, this trait of NU helped me overcome the challenge of being ‘thrown in to the deep-end’ when I was invited to the post of Chairman of the Board of Investment. Being 35 at the time, the first few months in the hot seat overwhelmed me: the sheer volume of letters and files numbering around 75 per day to incessant requests for appointments, to sitting on numerous talk-shops that the public service refers to as ‘committees’ and ‘task forces.’ It was NU’s habit of commencing work at dawn that helped me overcome job stress: The 2-3 hours of work I put in before reaching the office allowed me to clear all my paperwork within 24 hours, and enabled me to do my strategic thinking in the process.

Another trait in NU was his inclination to challenge traditional boundaries. This earned him financial success, kudos, brickbats, and even near ruin of his financial empire. Let me, however, focus on what I perceive as NU’s greatest accomplishment – galvanising the banking industry in Sri Lanka towards greater customer focus through use of technology and other service innovations.

Sampath Bank, which NU founded in 1987, could be considered a ‘blue ocean strategy,’ to borrow a phrase from modern management parlance, describing business strategies that are not just focused on beating competition, but making them irrelevant by making a quantum leap in customer value. He was, without doubt, the catalyst of modern banking as we know it in Sri Lanka, creating the concept of ‘uni-banking’ – a first for South Asia. This enabled a customer to transact business at any of the Bank’s branches. Sampath Bank was the first to introduce longer banking hours and the first to own a fully networked ATM system, thus, popularising the SET (Sampath Electronic Teller) card.

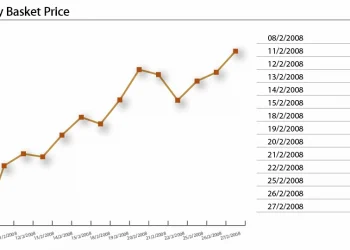

Sampath Bank was launched amidst much fanfare in 1987. The initial private placement I believe attracted more than 17,000 shareholders from all walks of life, giving the Bank the widest shareholding of any public company in Sri Lanka at the time. The advertising and PR that heralded the arrival of the bank and each of its branches was brilliantly executed by Irvin Weerakkody – a campaign that raised the bar for the advertising industry in Sri Lanka. The Bank experienced phenomenal growth in its formative years. By 1990, in its third full year of operations, deposits stood at Rs 2.7 bn, equivalent to slightly more than 50% of the deposit base of Hatton National and Commercial Banks, which commenced business decades ago. The Bank was profitable from its first year of operations.

However, success attracted its share of growing pains. The last quarter of 1990 saw a run on the bank’s deposits, fuelled by rumours of instability, and a downturn in profitability. Adverse Central Bank strictures were imposed to restrict the Bank’s most profitable product – the savings account with limited cheque encashment. It was amidst this uncertainty that NU took a controversial step – promoting the writer to the position of Manager, Strategic Planning. I was the youngest by about five years to head a Department and hold the title of Manager, and without banking institute qualifications! This decision did not go down well with some in the senior management, though history should judge that my work strengthened the financial base of the bank.

The Initial Private Placement I Believe Attracted More Than 17,000 Hareholders From All Walks Of Life, Giving The Bank The Widest Shareholding Of Any Public Company In Sri Lanka At The Time.

It is during these turbulent times that I began to best understand the inner workings of NU’s mind and that of the Bank and the challenges facing the management to restore confidence, whilst pursuing an aggressive expansion strategy of achieving NU’s original target of 50 branches in five years. The first ‘reality check’ I received was when my departing predecessor asked me the question, “So, did you join the Bank because you are a Sinhala Buddhist?” I immediately retorted and said, “No, I joined despite this as I do not agree with the concept of racial division.” I felt qualified to say this, since at the time, I was the Captain of the Tamil Union division one cricket team.

To truly understand the underlying ethos of the bank as reflected in its then tag line, ‘A truly Sri Lankan Bank for Sons of the Soil,’ I recall reading some of NU’s writings. He wrote of the persecution meted out by British rulers and those who ran the state banks restricting access to credit to the Sinhala entrepreneur. He also wrote about how the wave of nationalisation and land reform in the 1970s vastly diminished, if not destroyed, the wealth-base of Sri Lankan entrepreneurs of all ethnic groups. He wrote of his yearning to propagate barefoot banking to the poor, development banking to the rural entrepreneur and of making good the damage done to the Sri Lankan entrepreneurial spirit through years of colonisation, nationalisation, and later, the ethnic conflict. This was not a racist philosophy – this was a policy to uplift the willing and able economically by making him or her part of the banking system. This was the noble philosophy behind Sampath Bank as envisioned by NU – a bank founded by the people for the people.

Has Sampath Bank achieved the vision of its founding father, N U Jayawardena? According to published financial statements for 2006, the bank had assets over Rs 100 bn, deposits of over Rs 80 bn, market capitalisation of Rs 7.5 bn, profits of over Rs 1 bn and a branch network of over 100. This, to the writer, seems a commendable performance. Yet, knowing NU, he would not have been satisfied. He would argue that Sampath Bank is still the 7th largest bank in Sri Lanka, behind Commercial Bank and Hatton National. Sampath’s 6% market share of banking system assets is just a marginal improvement of the 5% share it had in the early 1990s. Quite simply, NU’s vision was for Sampath to become Sri Lanka’s largest private bank in the shortest possible time.

Yes, NU was a man in a hurry. He demanded from his executives the same discipline and dedication he possessed. And often, he perceived them as falling short, resulting in NU intervening in the day-to-day management of companies he headed. To many he was a paradox. Having been moulded by the depravation and discrimination he had to face as a consequence of his humble beginnings, he wanted to attain economic emancipation for himself through learning and business success, and through Sampath Bank, he wanted the ‘sons of the soil’ to achieve economic prosperity. Yet, NU was out of step with the pluralistic and consensus building management style required of a public company such as Sampath Bank. He felt the necessity to take control to ensure the lesser mortals who were shareholders or executives fell in line. Possibly NU wanted to achieve as much as possible in a short span of time as he was aware of his own mortality with advancing age. A more plausible reason could be that he felt there was little time to lose as Sri Lanka’s economic growth was sub-par compared with other East Asian countries. Moreover, often, his advice to policy makers was perceived as an arrogant diatribe, attracting the wrath of powerful persons.

Yet, very few will question his significant contribution to the advancement of Sri Lanka’s banking and financial services industry. As often is the case, men of brilliance are misunderstood. It takes the less scholarly longer to comprehend what appeared obvious to NU at the outset. This is the hallmark of a visionary and there is no question in my mind that N U Jayawardena was a visionary in economics and finance. The fact, that much of his thoughts were not put into action in a timely and efficient manner, is underscored by Sri Lanka’s economic and business landscape, by and large remaining mired in mediocrity.

The writer is currently Group CEO/Managing Director of the Forbes & Walker Group.

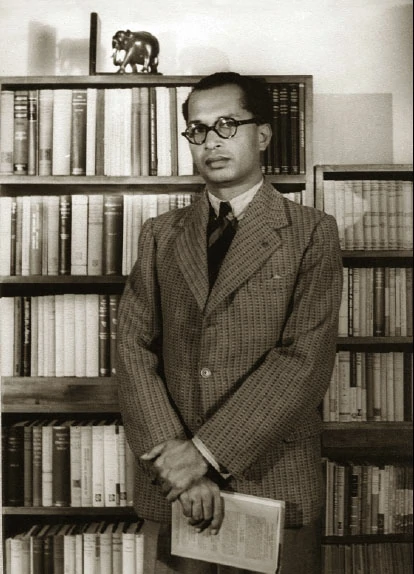

Photo Captions – With the PM SWRD Bandaranaike at the Parliament, A young N U Jayawardena, The family at home, N U Jayawardena and his wife, Their house in Tangalle, Hard at work in the 1930s